Sea turtles inhabit all the oceans of the world except the Arctic, and they therefore have a broad range of habitats and diets. Each species has uniquely evolved to different environments and available food [1]. Some are nomadic marathon swimmers and others call coral reefs their home. There are seven species of sea turtles found globally. So, who eats what and what does a sea turtle diet consist of?

An eggcellent start

All sea turtles start out life as eggs. Female turtles dig nests deep in the ground and lay clutches containing many eggs. Energy from the female turtle is stored as the egg yolk. This allows a sea turtle to fully develop from just a few cells to a fully formed independent hatchling [2].

Aside from the vital energy provided by the yolk, eggs also exchange heat, water, oxygen and carbon dioxide with other eggs and the surrounding sand [2][3].

The composition of the egg yolk is directly affected by the diet of the mother turtle [4]. Not only does the mother influence the nutritional content of her eggs, but she can also pass on unnatural chemicals and pollutants.

Human activity has led to harmful pollutants, like pesticides, being taken up by foraging turtles and passed on to their eggs [5].

Sea turtle diet by species

Green turtle diet: from carnivore to herbivour

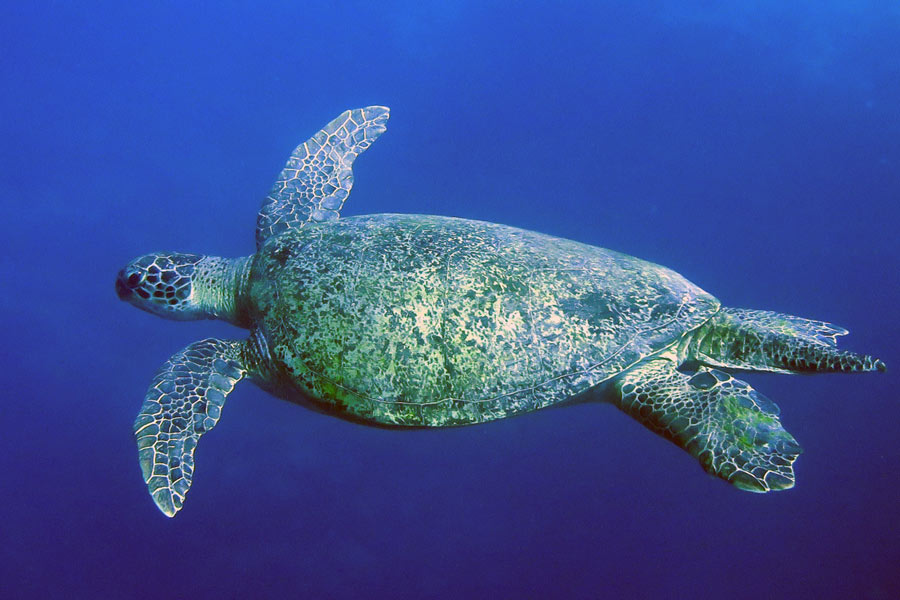

Green turtles begin their life living in open ocean near the surface. They start out with a generally carnivorous diet for the first 3-5 years, which can include zooplankton, mollusks, and crustaceans. [7]

As they grow, juvenile green turtles move to coastal waters and reefs and shift to a more herbivorous diet. Juvenile greens eat mainly seagrasses and algae [8], however, their diet can also include a number of invertebrate species such as jellyfish and sponges. [6][9].

As adults, green turtles have a unique “vegetarian” diet. Adult green turtles live in shallower waters with a primarily herbivorous diet, thriving on sea grass. [6] Just like cows grazing on terrestrial pastures, adult greens are going to ingest the occasional invertebrate together with the seagrass by accident.

Hawksbill turtle diet: mostly spongy

Hawksbill turtles start their life in the open ocean with a similar diet to green turtle hatchlings, [10] including macroplankton, barnacles, fish eggs, crabs, and algae [11][12].

Juvenile and adult hawksbill turtles live and thrive on coral reefs, primarily eating sponges [13][14]. While hawksbill turtles in the Caribbean live nearly exclusively of sponges, their Indian Ocean cousins feast on a wider range of organisms also including corals, sea urchins and jellyfish in their diet [11][13][15].

Leatherback diet: all About jellyfish

Leatherback turtles swim great distances, live in open ocean and primarily feed on jellyfish. In addition to true jellyfish, leatherback turtles have been reported to feed on other soft bodied organisms (pyrosomes and siphonophores) as well as squid and octopus. [11][15]

Olive ridley diet: all-eating

Adult olive ridleys tend to live in the open ocean with a broad omnivourous diet. Their diet includes crabs, mollusks, algae, jellyfish and shrimp [16]. They are also known to eat fish, showing opportunistic feeding behaviour [17][18]. Apart from the open ocean, olive ridley are also known to feed in shallower areas as “bottom feeders”, diving to feed on organisms living on the ocean floor [18][19].

Loggerhead diet: true carnivores

Loggerhead turtles are carnivores, feeding on a variety of prey depending on their life stage. [15]

Juvenile and adult loggerheads feed on a variety of crustaceans found on the ocean floor, including crabs, lobster and shrimp. They eat snails, mussels and even small amounts of sea grasses and algae [22][23][24]. There has also been reports of opportunistic feeding on fish caught or discarded by fishermen [25].

Kemps ridley diet: mostly crustaceans

Kemps ridley turtles are only found in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. Juvenile and adults primarily feed on crabs. They also eat other crustaceans and mollusks and occasionally fish – showing the ability to be opportunistic feeders. [20][21]

Flatback diet: soft bodied invertebrates

The Flatback sea turtle lives exclusively in Australia and little is known about the species and their diet throughout their lifetime. Juvenile and adult flatbacks are known to eat snails, jellyfish, corals and other soft bodied invertebrates.[26][27][28]

How does sea turtles’ diets affect the ocean ecosystems?

Sea turtles play a vital role in ocean ecosystems, affecting the diversity and function of ocean habitats [29]. Here are just a few examples.

Green Sea Turtles Maintain Healthy Seagrass Beds

Green sea turtles are vital in maintaining healthy beds of seagrass. They prevent seagrass becoming overgrown and by grazing they even improve the quality and growth of the grass [30]. Overgrown sea grass can decompose and develop a build up of algae, bacteria and fungus. The die-off of seagrass in Florida during the 1980s has been directly linked with the dramatic decline in green turtle populations [31].

Hawksbills Manage Sponges On Coral Reefs

Hawksbill turtles manage sponges on coral reefs. Sponges compete with corals for space on reefs and without predators they would quickly take over. Hawksbills are one of the few marine animals that can eat these toxic sponges, allowing corals to grow and thrive.[32][33]

Sea Turtles Keep Jellyfish Populations Under Control

Several species of sea turtles, but particularly the leatherback, play a key role in managing jellyfish populations. A top jellyfish predator, the huge size of leatherbacks means they can consume up to 200kg of jellyfish a day![34] Jellyfish eat fish eggs and larvae and compete for fish food. [35] So a decline in leatherbacks could mean more jellyfish and fewer fish in our oceans. [36]

Bottom Feeders Improve Aeration On the Sea Bed

Loggerheads and other species that feed on crustaceans on the ocean floor increase rates of nutrient recycling by crushing shells during feeding [29][37]. During their hunt for prey, loggerheads create trenches in the sea floor. By clearing sand they improve aeration and nutrient distribution on the sea bed, benefitting the ecosystem. [29][38]

What Sea Turtles Shouldn’t Eat

Sea turtles have survived for millions of years and each species has adapted to different diets. Through the natural abundance of the ocean, they have flourished in various habitats and available food sources. As we have just learnt, they also play key roles in a healthy marine ecosystem.

However, a new threat has emerged in the last few decades. A previously unknown material to marine life, plastic now pollutes our oceans [39]. Sea turtles around the world are ingesting plastic with devastating consequences. Plastic can cause blockages in the gut, malnutrition and death [40]. Globally, estimates of around 52% of all sea turtles have ingested plastic [41][42]. In some areas this estimate is even higher! For example, in a study off the coast of Brazil, turtles accidentally caught in fishing nets were examined and an astonishing 90% of juvenile green turtles were found to have ingested plastic [43].

Sea turtles ingest plastic most likely because they confuse the artificial material with actual food items. A plastic bag floating in the ocean can easily be mistaken for a jellyfish.If we want to protect sea turtles, and through them our oceans at large, we again have to rethink our plastic consumption and waste production.

Learn More About Sea Turtles

Enroll in our online courses to learn more about sea turtles. Both courses are free and designed for self-paced learning.

Sea Turtle Science & Conservation

Deep dive into sea turtle science and conservation. Suitable for budding conservationists and those with an interest in the science surrounding turtles, their biology and conservation.

e-Turtle School – All about sea turtles

Everything you have ever wanted to know about sea turtles, from evolution to conservation. Suitable for all sea turtles lovers and those who want to learn more about these fascinating creatures.

Got More Sea Turtle Questions?

Sea Turtles FAQ

Sea turtles can hold their breath for several hours, depending on their level of activity.

If they are sleeping, they can remain underwater for several hours. In cold water during winter, when they are effectively hibernating, they can hold their breath for up to 7 hours. This involves very little movement.

Although turtles can hold their breath for 45 minutes to one hour during routine activity, they normally dive for 4-5 minutes and surfaces to breathe for a few seconds in between dives.

However, a stressed turtle, entangled in a ghost net for instance, quickly uses up oxygen stored within its body and may drown within minutes if it cannot reach the surface.

Learn More About Sea Turtles – Free Online Courses

e-Turtle School – All about sea turtles

Everything you have ever wanted to know about sea turtles, from evolution to conservation. Suitable for all sea turtles lovers and those who want to learn more about these fascinating creatures.

Sea Turtle Science & Conservation

Deep dive into sea turtle science and conservation. Suitable for budding conservationists and those with an interest in the science surrounding turtles, their biology and conservation.

References:

- Hays GC, Akesson S, Broderick AC, Glen F, Godley BJ, Luschi P, Martin C, Metcalfe JD & Papi F 2001. The diving behaviour of green turtles undertaking oceanic migration to and from Ascension Island: dive durations, dive profiles and depth distribution. Journal of Experimental Biology 204: 4093-4098.

- Hays GC, Hochscheid S, Broderick AC, Godley BJ & Metcalfe JD 2000. Diving behaviour of green turtles: dive depth, dive duration and activity levels. Marine Ecology Progress Series 208: 297-298.

- Hochscheid S, Bentivegna F & Hays GC 2005. First records of dive durations for a hibernating sea turtle. Biology Letters 1: 82-86.

- Lutz PL and Musik JA (eds.) 1996. The Biology of Sea Turtles Volume I. CRC Press.

The actual documentation of a sea turtle’s age in the wild is difficult or nearly impossible. Individual turtles can be tracked for a shorter time of six month to three years with the help of satellite transmitters. Longterm studies rely on capture-recapture principle, just like our turtle photo id project. Each photo of a turtle represents a recapture event documenting that the individual is still alive.

A study of nesting green turtles in Hawaii observed female turtles returning to nest for up to 38 years after they were first identified. Assuming the average age at first nesting activity of 24 years, this would show that green turtles can live to up to at least 62 years.

Similar estimates have been made for loggerhead turtles.

References:

- Dodd C 1988. Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. Ecology 88.

- Humburg IH and Balazs GH 2014. Forty Years of Research: Recovery Records of Green Turtles Observed or Originally Tagged at French Frigate Shoals in Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, 1973-2013. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-PIFSC-40.

When sea turtles are juveniles, it is very difficult to tell their sex by eye as they do not differ externally. However, after reaching sexual maturity male sea turtles develop a long tail, which houses the reproductive organ. The tail may extend past the hind flippers.

Female turtles have a short tail, which generally doesn’t extend more than 10 cm (4 inches) past the edge of the carapace. Male sea turtles (except leatherbacks) have elongated, curved claws on their front flippers to help them grasp the female when mating.

The sex of a sea turtle embryo is determined by the temperature of the sand: warm temperatures result in more females while cooler temperatures result in more males.

The olive and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are the smallest species, growing only to about 70 cm (just over 2 feet) in shell length and weighing up to 45 kg (100 lbs). Leatherbacks are the largest sea turtles. On average leatherbacks measure 1.5 – 2m (4-6 ft) long and weigh 300 – 500 kg (660 to 1,100 lbs). The largest leatherback ever recorded was 2,56 m (8.4 ft) long and weighed 916 kg (2,019 lbs) !

Kemp’s Ridley

55.6-66.0 cm carapace length, weight range of 25-54 kg for nesting females.

References:

- Marquez-M R 1994. Synopsis of Biological Data on the Kemp’s Ridley Turtle, Lepidochelys kempi (Garman, 1880). NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-343.

Olive Ridley

Curved carapace length 52.5-80.0 cm, weight less than 50 kg (average 35.7 kg) for nesting females.

References:

- Qureshi M 2006. Sea turtles in Pakistan. In: Shanker K and Choudhury BC (Eds.). Marine Turtles of the Indian Sub- continent. Heydarabad: India Universities Press, pp. 217–224.Reichart HA 1993.

- Reichart HA 1993. Synopsis of biological data on the olive ridley sea turtle Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz 1829) in the western Atlantic. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-336.

Hawksbills

Nesting females reported between 53.3 and 95.5 cm carapace length, with weight between 27.2 and 86.2 kg.

References:

- Witzell WN 1983. Synopsis of biological data on the hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766). No. 137. Food & Agriculture Org.

Green turtles

Nesting green females reported curved carapace length 75-134 cm, weight (after egg deposition) 45-250 kg (!).

References:

- Hirth HF 1997. Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Green Turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758). Vol. 2. Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior.

Flatbacks

Ones study (Ref. 1) found nesting females have a mean curved carapace length 86.3 cm, and mean weight of 67.4 kg. Another study (Ref. 2) found flatbacks to be between 87.5-96.5 cm.

References:

- Schäuble C, Kennett R and Winderlich S 2006. Flatback Turtle (Natator depressus) nesting at Field Island, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia, 1990-2001. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 5: 188-194.

- Limpus CJ 1971. The Flatback Turtle, Chelonia depressa Garman in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Herpetologica 27: 431-446.

Loggerheads

Adult loggerhead turtles measure between 65 and 115 cm in curved carapace length and typically weigh between 40 and 180 kg. The largest recorded loggerhead weighed 545 kg and measured 213 cm in presumed total body length. On average, nesting, and therefore adult, female loggerheads have a curved carapace length of 65.1-114.9 cm and weigh between 40.0 and 180.7 kg. Males fall into the same size range (79.0-104.0 cm curved carapace length).

References:

- Brongersma LD 1972. European Atlantic turtles. Zoologische Verhandlingen 121, Leiden.

- Dodd C 1988. Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. Ecology 88: 1-119.

- Ernst CH and Lovich JE 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada, 2nd edition. John Hopkins University Press.

Leatherbacks

143.8-169.5 cm curved carapace length, weight 259-506 kg recorded for nesting females all around the world. Largest ever recorded specimen was found dead on a beach on the coast of Wales. The adult male turtle weighed 916 kg and its shell was 256.5 cm long. An autopsy revealed that it had drowned.

References:

- Eckert KL and Luginbuhl C 1988. Death of a Giant. Marine Turtle Newsletter 43: 2-3.

- Eckert KL, Wallace BP, Frazier JG, Eckert SA and Pritchard PCH 2012. Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Biological Technical Publication BTP-R4015-2012, US Fish & Wildlife Service.

Sea turtles cannot breathe underwater, however they can hold their breath for long periods of time. Sea turtles can hold their breath for several hours depending on their level of activity. For instance, a resting turtle can remain underwater for 4-7 hours whereas a foraging individual may need to surface more frequently.

When turtles hold their breath, their heart rate slows significantly to conserve oxygen – up to nine minutes may pass between heart beats! Despite this adaptation, a stressed turtle – such as one entangled in ghost net – will deplete oxygen stores rapidly and may drown within minutes if unable to reach the surface.

References:

- Long dive interval during hibernation: Hochscheid S, Bentivegna F & Hays GC 2005. First records of dive durations for a hibernating sea turtle. Biology Letters 1: 82-86.

- Dive duration during activity: Hays GC, Akesson S, Broderick AC, Glen F, Godley BJ, Luschi P, Martin C, Metcalfe JD & Papi F 2001. The diving behaviour of green turtles undertaking oceanic migration to and from Ascension Island: dive durations, dive profiles and depth distribution. Journal of Experimental Biology 204: 4093-4098.

- Hays GC, Hochscheid S, Broderick AC, Godley BJ & Metcalfe JD 2000. Diving behaviour of green turtles: dive depth, dive duration and activity levels. Marine Ecology Progress Series 208: 297-298.

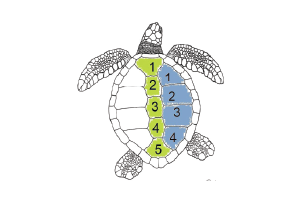

Yes, sea turtles can feel it when you touch their shell. Sea turtle shells consist of bones, which are covered by a layer of so-called scutes (plates). These scutes are made of keratin, the same material that human fingernails are made of. There are nerve endings enervating even the bones of the shell. These nerve endings are sensitive to pressure, for example from a touch on the back.

References:

- Thomson JS 1932. The Anatomy of the Tortoise. Scientific Proceedings of the Royal Dublin Society.

- Zangerl R 1969. The turtle shell. In: Gans C and Bellairs A (eds.): The Biology of Reptilia, Vol. 1: 311-319. Academic Press, New York.

There is no way to determine the exact age of a sea turtle from its physical appearance other than to establish if it is a hatchling, juvenile or adult, depending on its size.

In the Indian Ocean, hawksbills and greens are smaller than their counterparts elsewhere. Good information on size at maturity does not exist for the northern Indian Ocean. It’s tricky to tell visually if an animal is mature or not, especially females: they can be big enough but not actually be sexually mature.

After it’s death, the age of a turtle can be determined by a technique called “skeletochronology”, whereby the humerus (arm bone) is examined. These bones reveal growth rings that allow the turtle’s age to be calculated, much like we can calculate the age of a tree.

References:

- Snover ML 2002. Growth and ontogeny of sea turtles using skeletochronology: methods, validation and application to conservation. PhD Thesis, Duke University, USA.

In the past 100 years, human demand for turtle meat, eggs, skin, and shells have reduced their populations. Destruction of feeding and nesting habitats and pollution of the world’s oceans are all taking a serious toll on the remaining sea turtle populations.

Many breeding populations have already disappeared, and some species are being threatened to extinction. The natural obstacles faced by young and adult sea turtles are staggering, but it is the increasing pressures from the presence of humans that are threatening their future survival.

Click to watch a short video about barnacles.

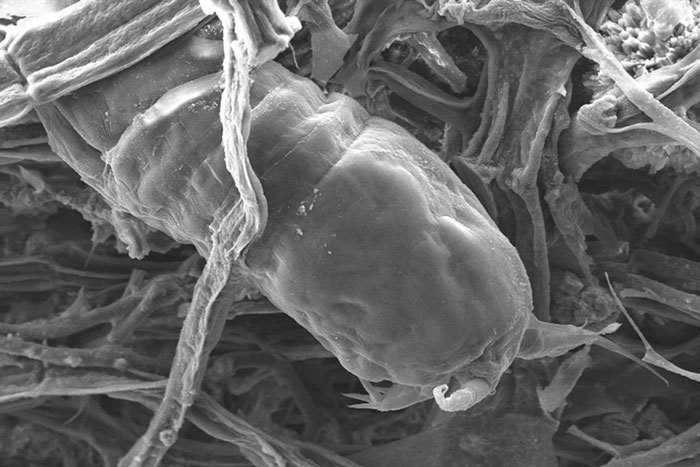

Barnacles are a highly specialized group of crustaceans. They have developed a sessile lifestyle as adults, attaching themselves to various substrates such as rocks, ships, whales or to sea turtles. Most commonly found barnacles on sea turtles belong to the genus Chelonibia, named after their host (Chelonia = turtle).

Initially, barnacles produce larvae. These early life stages are still mobile and facilitate further distribution. After the first six different so-called nauplius larvae, a seventh non-feeding larva develops: the cyprid. This is the stage which settles on a new substrate. The cyprid larvae has special attachment devices which allow it to hold onto the substrate, e.g. cup-shaped attachment organs on the antennae. Once settled, the barnacle develops into an adult and attaches in various ways: gripping the skin, cementing to the shell or boring into it.

Adult barnacles are filter feeders, thus benefit from a constant flow of water around them. As sessile creatures they can achieve that by a) settling in an area with pronounced water movement (e.g. close to shore) or b) settling on a moving substrate such as a sea turtle.

Even though barnacles are quite safely attached, barnacles actually are capable of moving as adults! They most likely achieve this through an extension of their cemented base as well as through muscle activity.

Most barnacles do not hurt sea turtles as they are only attached to the shell or skin on the outside. Others though burrow into the skin of the host and might cause discomfort and provide an open target area for following infections.

Excessive barnacle cover can be a sign of general bad health of a turtle. Usually sea turtles are debilitated first, and then become covered in an extensive amount of other organisms, such as barnacles and algae.

Luckily turtles are very resilient and can sometimes recover from such infestations.

Read more about Sea Turtle Hitchhikers – The Symbiotic Relationships of Sea Turtles here.

Learn More About Sea Turtles – Free Online Courses

e-Turtle School – All about sea turtles

Everything you have ever wanted to know about sea turtles, from evolution to conservation. Suitable for all sea turtles lovers and those who want to learn more about these fascinating creatures.

Sea Turtle Science & Conservation

Deep dive into sea turtle science and conservation. Suitable for budding conservationists and those with an interest in the science surrounding turtles, their biology and conservation.

References:

- Monroe R & Limpus CJ 1979. Barnacles on turtles in Queensland waters with descriptions of three new species. Memoires of the Queensland Museum 19: 197-223.

- Moriarty JE, Sachs JA & Jones K 2008. Directional Locomotion in a Turtle Barnacle, Chelonibia testudinaria, on Green Turtles, Chelonia mydas. Marine Turtle Newsletter 119: 1-4.

- Zardus, JD & Hadfield MG 2004. Larval development and complemental males in Chelonibia testudinaria, a barnacle commensal with sea turtles. Journal of Crustacean Biology 24: 409-421.

- Monroe R & Limpus CJ 1979. Barnacles on turtles in Queensland waters with descriptions of three new species. Memoires of the Queensland Museum 19: 197-223.Ross A & Frick MG 2007.

- From Hendrickson (1958) to Monroe & Limpus (1979) and Beyond: An Evaluation of the Turtle Barnacle Tubicinella cheloniae. Marine Turtle Newsletter 118: 2-5.

Sea turtles have many recognized roles in the evolution and maintenance of the structure and dynamics of marine ecosystems; they are an integral part of the interspecific interactions in marine ecosystems as prey, consumer, competitor, and host. They also serve as significant conduits of nutrient and energy transfer within and among ecosystems; and can also substantially modify the physical structure of marine ecosystems.

Sea turtles are an important part of the planet’s food web and play a vital role in maintaining the health of the world’s oceans. They regulate a variety of other organisms simply through eating them. For example, green turtles mainly feed on seagrass. By grazing on seagrass meadows, they prevent the grass from growing too long and suffocating on itself. Nice and healthy seagrass beds again perform a multitude of so-called ecosystem functions: they are a nursery ground for many marine species and additionally are an important carbon sink and oxygen provider in the ocean.

Another example are hawksbill turtles, who are mostly focused on eating sponges. Their sponge consumption is very important for a healthy coral reef by keeping the fast-growing sponges at bay and giving slower growing corals the chance to grow. Coral reefs are thought to be the most diverse ecosystem on the planet, providing habitats and shelter for thousands of marine organisms. Many fish spawn on the coral reefs and juvenile fish spend time there before heading out to deeper waters when they mature. Coral reefs also protect coastlines from wave action and storms and are an important revenue generator for many nations through tourism.

Leatherbacks eat jellyfish. Keeping the jellyfish population in check is important. Jellyfish prey on fish eggs and larvae and too many jellyfish means fewer fish.

Loggerheads feed on hard-shelled prey, such as crustaceans. By breaking up these shells, they increase the rate at which the shells disintegrate and, as a result, increase the rate of nutrient recycling in the ocean bottom ecosystems.

Sea turtles also provide habitat for many marine organisms! Barnacles, algae and small creatures called epibionts attach themselves to the turtle and by carrying these around, the sea turtles provide a food source for fish and shrimp. In fact, some fish species obtain their diet strictly from epibionts found on sea turtles.

Apart from that, sea turtles provide an important food source for other organisms, especially in their early life stages. Ants, crabs, rats, raccoons, foxes, coyotes, feral cats, dogs, mongoose and vultures are known to dig up unhatched turtle eggs; the eggs are a nutrient-rich source of food. Juvenile turtles are a food source for various sea birds, fish and invertebrates. Adult sea turtles are preyed upon by sharks and killer whales.

Unhatched eggs and empty eggshells remaining inside nests on the beaches are a fertilizer for beach vegetation – they provide nutrition for plant growth with helps stabilize the shoreline as well as provide food for a variety of plant eating animals.

Because sea turtles can migrate huge distances, they also play an important role in generating and maintaining diversity throughout the world’s oceans by transporting the organisms that live on them to and from reefs, seagrass beds and the open ocean.

References:

- Bjorndal, K. A., & Jackson, J. B. (2002). 10 Roles of sea turtles in marine ecosystems: reconstructing the past. The biology of sea turtles, 2, 259.

- León, Y. M., & Bjorndal, K. A. (2002). Selective feeding in the hawksbill turtle, an important predator in coral reef ecosystems. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 245, 249-258.

Although some sea turtles may return to the beach where they were born to nest (natal homing), equally many will nest on a different beach in the same region where they were born. There are several theories as to how sea turtles are able to return to their birthplace to nest, but none have yet been proven. The most common theories are:

- They can detect both the angle and intensity of the earth’s magnetic field. Using these two characteristics, a sea turtle may be able to determine its latitude and longitude, enabling it to navigate virtually anywhere. Early experiments seem to show that sea turtles have the ability to detect magnetic fields. Whether they actually use this ability to navigate is the next idea being investigated.

- It is believed that hatchlings imprint the unique qualities of their natal beach while still in the nest and/or during their trip from the nest to the sea. Beach characteristics used may include smell, low-frequency sound, magnetic fields, the characteristics of seasonal offshore currents and celestial cues.

- Younger female turtles may follow older, experienced nesting turtles from their feeding grounds to the breeding site.

References:

- Lohmann KJ and Lohmann CMF 1992. Orientation to oceanic waves by green turtle hatchlings. Journal of Experimental Biology 171: 1-13.

- Lohmann KJ, Lohmann CMF, Ehrhart LM, Bagley DA and Swimg T 2004. Geomagnetic map used in sea-turtle navigation. Nature 428: 909-910.

Sea turtles drink seawater to hydrate. Although sea turtles are physically adapted to a saline environment, they need to be able to excrete excess salt. As reptilian kidneys are unable to excrete large volumes of salt via urine, sea turtles evolved specialised secretory glands (lachrymal glands) located in the corner of each eye to remove excess salt. The liquid secreted gives the appearance of tears, hence why turtles are often reported to “cry” .

References:

- Reina, R.D. Jones, T.T. and Spotila, J.R. 2002. Salt and water regulation by the leatherback sea turtle Dermochelys coriacea. Journal of Experimental Biology, 205(13), 1853-1860.

Leatherbacks can dive to a depth of more than 1,300 meters (4,265 feet) in search of their prey, jellyfish. The hard-shelled species dive at shallower depths, typically up to 175 meters (500 feet) though olive ridleys have been recorded at over 200 meters (660 feet).

The leatherback is adapted to deep dives because it lacks a rigid breastbone. Its leathery shell also absorbs nitrogen, reducing problems arising from decompression during deep dives and resurfacing (i.e., “the bends”).

References:

- Leatherback turtle dives deeper than a Navy sub, smashing world record in the process, Live Science, June 14, 2024

- García-Párraga D, Crespo-Picazo JL, Bernaldo de Quirós Y, Cervera V, Martí-Bonmati L, Díaz-Delgado J, Arbelo M, Moore MJ, Jepson PD and Fernández A 2014. Decompression sickness (‘the bends’) in sea turtles. Diseases of aquatic organisms 111: 191-205.

- Houghton JDR, Doyle TK, Davenport J, Wilson RP and Hays GC 2008. The role of infrequent and extraordinary deep dives in leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). The Journal of Experimental Biology 211: 2566-2575.

- McNahon CR, Bradshaw CJA and Hays GC 2007. Satellite tracking reveals unusual diving characteristics for a marine reptila, the olive ridley turtle Lepidochelys olivacea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 329: 239-252.

The number of eggs in a nest, called a clutch, varies by species. On average, sea turtles lay 110 eggs in a nest, averaging between 2 to 8 nests a season. The smallest clutches are laid by Flatback turtles, approximately 50 eggs per clutch. The largest clutches are laid by hawksbills, which may lay over 200 eggs in a nest.

In the Maldives predominantly green and hawksbill turtles are nesting. On average green turtles lay a mean of 110 eggs per nest with the largest clutches ever recorded of up to 238 eggs! Our own studies show clutch size to be 77-124 eggs with the largest clutch recorded at 205 eggs.

Mean clutch size for hawksbills is significantly larger than that with around 150 eggs per nest in the Caribbean, variation is roughly the same with 86-206 eggs per nest. In the Indian Ocean data from the Seychelles shows even higher mean clutch size with 182 eggs per nest (160-242 range). The largest clutch recorded by the ORP on Félicité Island was 217 eggs!

Learn More About Sea Turtles – Free Online Courses

e-Turtle School – All about sea turtles

Everything you have ever wanted to know about sea turtles, from evolution to conservation. Suitable for all sea turtles lovers and those who want to learn more about these fascinating creatures.

Sea Turtle Science & Conservation

Deep dive into sea turtle science and conservation. Suitable for budding conservationists and those with an interest in the science surrounding turtles, their biology and conservation.

References:

- Hirth HF 1997. Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Green Turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758). Vol. 2. Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior.

- Bjorndal KA, Carr, A, Meylan AB and Mortimer JA 1985. Reproductive Biology of the Hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata at Tortuguero, Costa Rica, with Notes on the Ecology of the Species in the Caribbean. Biological Conservation 34: 353-368.

- Diamond AW 1976. Breeding Biology and Conservation of Hawksbill Turtles, Eretmochelys imbricata L., on Cousin Island, Seychelles. Biological Conservation 9:199-215. (Hughes 1974b)

Sea turtles are generally slow swimmers traveling at a speed of 2.8 to 10 km/h (1.7 to 6.2 mp/h) with slight variation between the species.

The leatherback sea turtle has been recorded swimming as fast as 35 km/h (22 mph), according to the San Diego Zoo. This speed is usually just achieved during brief bursts, for example due to flight reactions.

References:

- Eckert SA 2002. Swim speed and movement patterns of gravid leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) at St Croix, US Virgin Islands. Journal of Experimental Biology 205: 3689-3697.

- Papi F, Luschi P, Croisio E and Hughes GR 1997. Satellite tracking experiments on the navigational ability and migratory behaviour of the loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta. Marine Biology 129: 215-220.

Yes, sea turtles can drown as they have lungs just like other reptiles and similar to our own lungs. Sea turtles cannot breathe underwater, however they can hold their breath for long periods of time. However, a stressed sea turtle, such as one entangled in a ghost net for example, will deplete oxygen stores rapidly and may drown within minutes if unable to reach the surface.

Sea turtle drownings have been documented when turtles became caught in active fishing nets or ghost gear. Typical signs of drowning include a comatose state, lack of reflexes, water in the lungs and specific tissue alterations in the lung, which are visible on radiographs.

Not all turtles die immediately and while still in the water. Once turtles are comatose, they have about a 50 % chance of recovery.

References:

- Norton TM 2005. Chelonian emergency and critical care. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 14 (2): 106-130.

- Pointer IR and Harris ANM 1996. Incidental capture, direct mortality and delayed mortality of sea turtles in Australia’s Northern Prawn Fishery. Marine Biology 125: 813-825.

When sea turtles mate, the male sea turtle climbs onto the female sea turtle’s back and holds on to her carapace with the long, sharp claws of his front flippers. The way he hooks on to the edge of the female’s shell often results in a scratched shell and bleeding wounds in the soft parts of her body. Copulation can take place on the surface or under water.

The reproductive organs of both male and female sea turtles are located at the base of their tails in their cloaca – a combined intestinal, urinary, and reproductive organ. Male sea turtles have a very long tail while female sea turtles have a short tail. The male’s penis is located in his cloaca. He reaches his tail underneath the posterior end of the female’s shell to inseminate her cloaca.

No. Once a nest has been laid, the female never returns to it. The eggs and hatchlings are left to fend for themselves and locate the water upon emerging.

Reference:

- Spotila JR 2004. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behaviour and Conservation. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA.

Most barnacles do not hurt sea turtles, as they are only attached to the shell or skin on the outside. Others though burrow into the skin of the host and might cause discomfort and provide an open target area for following infections.

Excessive barnacle cover can be a sign of general bad health of a turtle. Usually sea turtles are debilitated first, and then become covered in an extensive amount of other organisms, such as barnacles and algae.

Luckily turtles are very resilient and can sometimes recover from such infestations.

References:

- Monroe R & Limpus CJ 1979. Barnacles on turtles in Queensland waters with descriptions of three new species. Memoires of the Queensland Museum 19: 197-223.

- Ross A & Frick MG 2007. From Hendrickson (1958) to Monroe & Limpus (1979) and Beyond: An Evaluation of the Turtle Barnacle Tubicinella cheloniae. Marine Turtle Newsletter 118: 2-5.

No, sea turtles cannot retract their heads into their shells. Their bodies are well adapted to swimming with generally flatter shells as opposed to the high domed shells of tortoises. Sea turtles have the same muscles as other turtles, which allows them to pull back their heads, but there is simply not enough space in the shell to fully retract the head.

References:

- Wyneken J 2001. The Anatomy of Sea Turtles: Part II. U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-470, 53-112.

- Valente ALS, Cuenca R, Zamora M, Parga ML, Lavin S, Alegre F and Marco I 2007. Computed tomography of the vertebral column and coelomic structures in the normal loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta). The Veterinary Journal 174: 362-370.

Sea turtles can survive in the wild with only three flippers as many sporadic sightings of turtles with such injuries show – they learn to adapt to a missing limb just like humans. If they are missing a front flipper, they learn to compensate by using their opposite back flipper when swimming, for example. We currently do not know if a missing limb is going to significantly influence the general life span of these turtles, as systematic studies are not easy to conduct.

One or two missing hindlimbs is going to have a great impact on female turtles, as they use these flippers to dig their nests. Unsuccessful digging can lead to abandoned nesting attempts.

References:

- Spotila JR & Tomillo PS (eds.) 2015. The Leatherback Turtle: Biology and Conservation. Johns Hopkins Press, Maryland, US.

It is difficult to predict the exact incubation time for turtle eggs. The hatching date depends on variables such as the temperature during incubation and the depth of the nest, for example.

In the Maldives, sea turtle nests incubate for approximately 49 to 62 days, whereas in colder regions around the world incubation can take up to 80 days.

In Kenya, turtle nests take between 40 and 73 days to incubate before hatching, varying between different nesting seasons and beaches along the coast. The shortest incubation period was recorded on the northern part of the coast.

Incubation time in Iran, in the Gulf of Oman, is at mean 61.7 days.

References:

- Hudgins JA, Hudgins EJ, Ali K and Mancini A 2017. Citizen science surveys elucidate key foraging and nesting habitat for two endangered marine turtle species within the Republic of Maldives. Herpetology Notes 10: 463-471.

- Matsuzawa Y, Sato K, Sakamoto W and Bjorndal KA 2002. Seasonal fluctuations in sand temperature: effects on the incubation period and mortality of loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) pre-emergent hatchlings in Minabe, Japan. Marine Biology 140: 639-646.

- Okemwa GM, Nzuki S and Mueni EM 2004. The Status and Conservation of Sea Turtles in Kenya. Marine Turtle Newsletter 105: 1-6.

- Olendo MI, Okemwa GM, Munga CN, Mulupi LK, Mwasi LD, Mxolisi Sibanda HBM and Ong’anda HO 2019. The value of long-term, community-based monitoring of marine turtle nesting: a study in the Lamu archipelago, Kenya. Oryx, doi:10.1017/S0030605317000771.

- Sinaei M, Bolouki M, Ghorbganzadeh-Zaferani G, Matin MT, Alimoradi M and Dalir S 2018. On a Poorly Known Rookery of Green Turtles (Chelonia mydas) Nesting at the Chabahar Beach, Northeastern Gulf of Oman. Russian Journal of Marine Biology 44: 254-261.

It is very hard to say how many sea turtles are left. Sea turtles are not easy to count, so we use different methods to estimate population sizes.

One such measure used is the annual number of nesting events in each population. Since turtles can lay more than one clutch per year, the number of nests does not directly translate to adult females in a population. Additionally, sea turtles do not reproduce every year. An average of 2-6 years (depending on the species) can pass between active reproduction for each female.

Scientists take several factors into account when they convert observed nesting activity into the estimated population size. These include remigration interval, proportion identified & resighted females, sex ratio etc. A recent publication evaluating this process recommends caution that our current overall estimates of population sizes might still be too optimistic.

Recent estimates show us that there are nearly 6.5 million sea turtles left in the wild with very different numbers for each species, e.g. population estimates for the critically endangered hawksbill turtle range from 83,000 to possibly only 57,000 individuals left worldwide. Kemp’s ridley and flatback turtles each with a very narrow distribution could have less than 10,000 individuals left for each species (medium estimates: 25,000 and 69,000 respectively).

In general it is best to evaluate conservation efforts by assessing trends. We can see that conservation measures are fruitful in certain areas, because the general numbers of observed turtle nests increased over the years, even though we do not have specific numbers for individual turtles in the area.

References:

- Casale P & Ceriani SA 2020. Sea turtle populations are overestimated worldwide from remigration intervals: correction for bias. Endangered Species Research 30: 141-151.

- Mazaris AD, Schofield G, Gkazinou C, Almpanidou V & Hays GC 2017. Global sea turtle conservation successes. Science Advances 3.

- Spotila JR 2004. Sea Turtles: A complete guide to their biology, behaviour, and conservation. John Hopkins University Press, Maryland, US.

- Wallace BP 2020. How many sea turtles are there? SWOT Report XV: 41.

Yes, sea turtles have tails. In fact, once sea turtles reach sexual maturity, the size of the tail can be used to reliably distinguish between male and female sea turtles. Males develop much longer tails – which may extend past their rear flippers – whereas females tails remain much shorter.

The tail of both male and female sea turtles contain a cloaca – a posterior opening for digestive, urinary and reproductive tracts – and, as such, the tail plays a crucial role in sea turtle reproduction.

References:

- Godley, B.J., Broderick, A.C., Frauenstein, R., Glen, F. and Hays, G.C. 2002. Reproductive seasonality and sexual dimorphism in green turtles. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 226, 125-133.

- Hendrickson, J.R. 1958. The green turtle Chelonia mydas in Malaya and Sarawak. Proc Zool Soc Lond, 130, 455-535.

Just like other reptiles, sea turtles have lungs. They have a slightly different structure than mammalian lungs, but work just as well when it comes to exchanging gases (oxygen and carbondioxide). The lungs are located right under the carapace and the vertebral column.

Ventilation of the lungs (breathing) is achieved by movements of the muscles attached to the pelvic and shoulder girdles and to the plastron. You can sometimes see turtles ‘rocking‘ their shoulders when they are not underwater; this movement of the muscle masses around the shoulder also helps them breathe by changing the pressure inside the lungs.

References:

- Wyneken J 2001. The Anatomy of Sea Turtles: Part II. U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-470, 53-112.

Most sea turtles are predated during their hatchling stage. Their small size and limited swimming speed makes them easy targets for crabs, sea birds, and wild and domestic mammals on their way from their nest to the beach. Synchronized, mass hatching is their main strategy to avoid predators at this stage.

Once in the water, hatchlings are still highly predated by carnivorous fish, sea birds, and pretty much any animal with a big appetite and a big mouth!

As they grow older, their hard-shell provides them a shield from predator attacks, making them harder to get eaten. Sharks and killer whales are the main predator of adult sea turtles. Shark avoidance by sea turtles is hard to study in the wild, and most of what we know is directly observing how sea turtles behave around these predators. Encounters between sharks and turtles are difficult to observe, as shark populations are now severely depleted throughout the world.

However, some studies looking at turtle diving behavior suggest that U-shaped dives of green turtles might function as both resting dives and predator avoidance, while a slow approach to the surface to breathe, using a passive ascent under positive buoyancy, allows the turtles to scan the habitat for predators before surfacing. If an attack is imminent, sea turtles have been seen turning their shell to the shark’s mouth as it approaches, thus preventing the shark from biting their flippers or soft tissues, and swimming fast in the opposite direction.

References:

- Heithaus, M. R., Wirsing, A. J., Thomson, J. A., & Burkholder, D. A. (2008). A review of lethal and non-lethal effects of predators on adult marine turtles. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 356(1-2), 43-51.

Sea turtles eggs must incubate in moist sand. For this reason, every year, some beaches around the tropical and temperate world are visited, mostly at night, by adult females who come ashore to dig a nest chamber and there, deposit their eggs.

It is a common belief that only females come ashore. However, in some places in the world where waters are a little bit colder, turtles of both sexes may be found basking in the sun on the beach! This basking behaviour in sea turtles is linked to thermoregulation (regulation of the body temperature), and is commonly seen for green turtles of the Galapagos, Hawaiian and Wellesley archipelagos. As sea turtles are poikilothermic, meaning that they can not internally maintain their body temperature and must absorb heat from the surrounding environment to maintain optimal body temperature, this behaviour helps the turtles in warming their internal temperatures by up to 3ºC! There are also some speculations that basking may aid immune function, predator avoidance, digestion, egg development and even prevent unwanted courtship.

References:

- Mrosovsky, N. (1980). Thermal biology of sea turtles. American Zoologist, 20(3), 531-547.

- Spotila, J. R., & Standora, E. A. (1985). Environmental constraints on the thermal energetics of sea turtles. Copeia, 694-702.

- Van Houtan, K. S., Halley, J. M., & Marks, W. (2015). Terrestrial basking sea turtles are responding to spatio-temporal sea surface temperature patterns. Biology letters, 11(1), 20140744.

Sea turtles have several natural predators; these vary depending upon the sea turtle’s life stage.

Racoons, foxes, coyotes, feral dogs, ants, crabs, armadillos and mongooses can unearth and eat sea turtle eggs before they have the chance to hatch; crabs and birds can eat hatchlings as they run from the nest to the ocean, and fish (including sharks) and dolphins can eat hatchlings as they move from coastal waters towards the open ocean.

Although sea turtles have fewer predators as they increase in size, sharks and killer whales can predate adult sea turtles in-water, and jaguars and crocodiles have been known to predate adult female sea turtles as they climb ashore to nest.

References:

- Heithaus, M.R. 2013. 10 Predators, Prey, and the Ecological Roles of Sea Turtles. The Biology of Sea Turtles, 3, 249.

- Heithaus, M.R, Wirsing, A.J, Thomson, J.A. and Burkholder, D.A. 2008. A review of lethal and non-lethal effects of predators on adult marine turtles. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 356(1-2), 43-51.

Sea turtles scratch their shells to clean them. This self-grooming behaviour helps them remove epibionts such as barnacles or algae. Excessive epibiont growth would otherwise impair the turtle’s movement and swimming ability.

References:

- Frick MG and McFall G 2007. Self-Grooming by Loggerhead Turtles in Georgia, USA. Marine Turtle Newsletter 118: 15.

- Schofield G, Katselidis KA, Dimopolous P, Pantis J and Hayes GC 2006. Behaviour analysis of the loggerhead turtles Caretta caretta from direct in-water observations. Endangered Species Research 2: 71-79.

During the course of incubation, the embryo grows inside the egg from a few cells at the beginning to a self-sufficient animal hatching (coming out of the egg) some 50 to 80 days later. Hatching typically begins with the baby turtle using a small, point keratinous bump on the tip of their snout (called caruncle) to break the egg.

As there are many eggs in each nest, and they are buried several centimetres in the sand, baby turtles will hatch almost synchronously with their siblings to allow simultaneous digging to make their way out of the nest faster! This behaviour is called ‘social facilitation’ as the synchronous effort of many individuals might be needed to dig successfully through the column of sand above the nest chamber. This effort may take 3-5 days in total as intense digging activity also needs some time of resting.

Once one of the hatchlings decides it is time to continue, its digging will trigger its siblings to do the same. Hatchlings are also clever in avoiding high temperatures. Emerging during daylight and under the hot sun can cause heat exhaustion, and the hatchlings will be more exposed to predators. Therefore, most hatchlings will emerge after the sand cools in the late afternoon or at night, or during cool cloudy days. Hatching simultaneously is also a clever idea to decrease the overall predation rate of the baby turtles as they leave the beach and swim out to sea. Once they emerge at the sand surface, they will quickly crawl towards the ocean.

References:

- Carr, A., & Hirth, H. (1961). Social facilitation in green turtle siblings. Animal Behaviour, 9(1-2), 68-70.

- Rusli, M. U., Booth, D. T., & Joseph, J. (2016). Synchronous activity lowers the energetic cost of nest escape for sea turtle hatchlings. Journal of Experimental Biology, 219(10), 1505-1513.

- Saito, T., Wada, M., Fujimoto, R., Kobayashi, S., & Kumazawa, Y. (2019). Effects of sand type on hatch, emergence, and locomotor performance in loggerhead turtle hatchlings. Journal of experimental marine biology and ecology, 511, 54-59.

Sea turtles use different cues to navigate the oceans. During the very early stage, when a turtle first enters the sea, it uses the direction of the waves for orientation. Usually, swimming directly perpendicular towards the waves will take hatchlings directly seaward and away from the shore. The juvenile turtles do not need to see the waves for that, but use the orbital movement of the waves, most likely detected with the inner ear (sense of balance).

Part of their navigation system in the open ocean is the earth’s magnetic field! Depending on the specific location on earth, the magnetic field has a specific inclination and intensity. Sea turtles seem to be able to sense this signature. When turtles are placed experimentally in the magnetic field of a different location with the use of an electric coil, they will adapt swimming directions as if they have changed to the location of the magnetic field!

References:

- Lohmann KJ and Lohmann CMF 1992. Orientation to oceanic waves by green turtle hatchlings. Journal of Experimental Biology 171: 1-13.

- Lohmann KJ, Lohmann CMF, Ehrhart LM, Bagley DA and Swimg T 2004. Geomagnetic map used in sea-turtle navigation. Nature 428: 909-910.

The sex of sea turtles is not determined purely genetically, as it is in humans. The temperature during the development of the embryo will determine whether a male or a female turtle hatches. Higher temperatures result in females, lower in males.

Increasing sand temperatures on nesting beaches can therefore shift the sex ratio of hatchlings to almost entirely female. As a result, turtles may have a problem reproducing in the future.

References:

- Abella Perez E, Marco A, Martins S and Hawkes L 2016. Is this what a climate change-resilient population of marine turtles looks like? Biological Conservation 193: 124-132.

- Chaloupka M, Kamezaki N and Limpus C 2008. Is climate change affecting the population of the endangered Pacific loggerhead sea turtle? Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 356: 136-143.

- Fuentes MMPB, Limpus CJ and Hamann M 2011. Vulnerability of sea turtle nesting grounds to climate change. Global Change Biology 17: 140-153.

- Pike DA, Antworth RL and Stiner JC 2006. Earlier Nesting Contributes to Shorter Nesting Seasons for the Loggerhead Sea Turtle, Caretta caretta. Journal of Herpetology 40: 91-94.

One species of sea turtles, the hawksbill can affect reef diversity and succession by simply… eating! Hawksbills prefer eating sponges above anything else, which is very helpful to maintain a high coral cover on a reef. Scleractinian corals and sponges commonly compete for space on reefs, with sponges being more often the superior competitor. Sponges also compete for space, so predation by hawksbills is believed to have a major role in maintaining sponge species diversity.

Coral reefs are thought to be the most diverse ecosystem on the planet, providing habitats and shelter for thousands of marine organisms. Many fish spawn on the coral reefs and juvenile fish spend time there before heading out to deeper waters when they mature. Coral reefs also protect coastlines from wave action and storms and are an important revenue generator for many nations through tourism.

References:

- Bjorndal, K. A., & Jackson, J. B. (2002). 10 Roles of sea turtles in marine ecosystems: reconstructing the past. The biology of sea turtles, 2, 259.

- Jackson, J. B. (1997). Reefs since columbus. Coral reefs, 16(1), S23-S32.

Climate change can impact sea turtles in various ways. Firstly, increasingly warm seas pose a threat to vital sea turtle habitats and food sources, such as coral reefs. Cooler ocean temperatures are associated with higher productivity, thus providing more food for many organisms – including sea turtles. Warmer oceans and less food available leads to decreased nesting activity and fewer sea turtles being born. These effects have been monitored in some populations, e.g. in the Western Pacific Ocean and Western Atlantic.

Secondly, sea level rise can be very detrimental for sea turtle nesting beaches and it can be increasingly difficult for turtles to find appropriate spaces to deposit their eggs. This will also lead to decreased nesting activity and fewer sea turtles being born.

In addition to that, the sex of a sea turtle is not determined purely genetically as it is in humans: the temperature during the development of the embryo will determine whether a male or a female turtle hatches. Higher temperatures result in females, lower in males. Increasing sand temperatures on nesting beaches can therefore shift the sex ratio of hatchlings to almost entirely female. As a result, turtles can have a problem reproducing in the future.

References:

- Abella Perez E, Marco A, Martins S and Hawkes L 2016. Is this what a climate change-resilient population of marine turtles looks like? Biological Conservation 193: 124-132.

- Chaloupka M, Kamezaki N and Limpus C 2008. Is climate change affecting the population of the endangered Pacific loggerhead sea turtle? Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 356: 136-143.

- Fuentes MMPB, Limpus CJ and Hamann M 2011. Vulnerability of sea turtle nesting grounds to climate change. Global Change Biology 17: 140-153.

- Pike DA, Antworth RL and Stiner JC 2006. Earlier Nesting Contributes to Shorter Nesting Seasons for the Loggerhead Sea Turtle, Caretta caretta. Journal of Herpetology 40: 91-94.

Sea turtles can perform a variety of thermoregulatory behaviours to stay warm in colder waters, such as basking at the surface of the water during the warmer times of the day, and in some cases, on beaches! Also, they tend to restrict their movements to warmer, tropical and temperate waters, or microclimates where water heats up faster (eg. shallow reefs and seagrass lagoons).

Leatherback turtles, however, are an exception. They may be found feeding in very colder waters (e.g. north of the arctic circle), where jellyfish are abundant. This is only possible as their black carapace acts as a good insulator, as well as their large layer of body fat (blubber) under their skin. This species also possess physiological control mechanisms that promote optimal heat exchange between their circulatory system and muscles.

References:

- Bostrom, B. L., Jones, T. T., Hastings, M., & Jones, D. R. (2010). Behaviour and physiology: the thermal strategy of leatherback turtles. PLoS One, 5(11).

- Paladino, F. V., O’Connor, M. P., & Spotila, J. R. (1990). Metabolism of leatherback turtles, gigantothermy, and thermoregulation of dinosaurs. Nature, 344(6269), 858-860.

Sea turtles are considered to be what is called a “keystone species”. The herbivorous green turtle and the sponge-eating hawksbill turtles are integral keystone species to any tropical marine ecosystem by performing critical ecological roles that are essential for the structure and function of these ecosystems.

For example, it has been suggested that the dramatic decline of these species in the Caribbean has radically reduced, and qualitatively changed, grazing and excavation of seagrasses, as well as depredation on marine sponges. This has in turn resulted in loss of production to adjacent ecosystems, such as coral reefs and disrupted entire food chains.

The leatherback turtle, which feed mainly on gelatinous prey such as jellyfish and salps, may consume the equivalent weight of an adult lion in jellyfish (440 lbs.) in a day. Recent studies show that jellyfish population’s blooms are more frequent and are continuously increasing in size and therefore have become problematic and are in fact a threat to the natural balance of marine ecosystems and towards human beings.

For this reason, the Leatherbacks play an essential role in controlling jellyfish population numbers and prevent the take over from a once fish populated ecosystem to a jellyfish abundant ecosystem in locations where fish stocks are already depleted.

References:

- Eckert, K. L., & Hemphill, A. H. (2005). Sea turtles as flagships for protection of the wider Caribbean region. Maritime Studies, 3(2), 4.

- Jackson, J. B. (1997). Reefs since columbus. Coral reefs, 16(1), S23-S32.

- Williams, J. (2015). Are jellyfish taking over the world. Journal of Aquactic and Marine Biology, 3, 00026.

- Wilson EG, Miller KL, Allison D, Magliocca M (2010) Why healthy oceans need sea turtles: the importance of sea turtles to marine ecosystems. Oceana protecting the world’s oceans, p.9.

Sea turtles eat a broad range of diets. Each sea turtle species has uniquely evolved to different environments and available food depending. Sea turtles therefore play a vital role in ocean ecosystems, affecting the diversity and function of ocean habitats by what they eat. Common for them all is that they all lack teeth!

The Specific Diet of Each Sea Turtle Species

Flatback Diet

Flatbacks are mainly carnivorous, feeding in shallow waters on soft bottoms. Little is known about this species’ diet throughout their lifetime, but juveniles and adults are known to eat snails, jellyfish, corals and other soft bodied invertebrates.

Green Turtle Diet

Green turtles are vegetarian and prefer sea grasses, sea weeds and algae as adults, however, green turtle hatchlings are omnivorous, eating jellyfish, snails, crabs, and shrimp.

Hawksbill Diet

Hawksbills have a bird-like beak that is used to cut through soft coral, anemones and sea sponges.

Kemp’s Ridley Diet

Kemp’s ridleys are omnivores at the beginning of their lives, feeding on seaweed and small creatures like crabs and snails. As adults, Kemp’s ridleys look for food on the seabed, feeding on crustaceans, fish, molluscs, squids and jellyfish.

Leatherback Diet

Leatherbacks feed mostly on jellyfish.

Loggerhead Diet

Loggerheads are carnivores, feeding on a variety of prey depending on their life stage but mainly on hard-shelled organisms such as lobsters, crustaceans, and fish.

Olive Ridley Diet

Olive ridleys are omnivorous, mostly eating jellyfish, snails, crabs, and shrimp but they will occasionally eat algae and seaweed as well.

Sea turtles are poikilothermic, meaning that they cannot maintain their internal body temperature efficiently and must therefore absorb heat from the surrounding environment to function normally. Depending on their life stage and species, sea turtles exposed to abrupt drops in temperatures may suffer from “cold-stunning”, or a form of hypothermia. Cold-stunned turtles can develop many clinical conditions, primarily lung, intestinal, skin and eye diseases, which often require urgent treatment to save the animal.

References:

- Anderson, E. T., Harms, C. A., Stringer, E. M., & Cluse, W. M. (2011). Evaluation of hematology and serum biochemistry of cold-stunned green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in North Carolina, USA. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 42(2), 247-255

Poaching means the illegal take, hunt or catch of wildlife. The take or harvest of sea turtles and their eggs has been a traditional activity among many coastal communities for centuries. Most indigenous coastal tribes of many countries, specially in the tropics, capture sea turtles for subsistence and as a source of animal protein. This artisanal and subsistence take, primarily for local consumption, was likely occurring at sustainable levels at first.

The consumption and trade of sea turtles became more common in the temperate zones during the colonisation of the New World. Whalers and ocean explorers exploited sea turtles as a supply of fresh meat during the long journeys across the Atlantic ocean between the Caribbean sea to Europe, as turtles were found to withstand several weeks alive inside the boats without food, or water!

Sea turtle meat was introduced in Europe as a delicacy by the end of the 19th century, with green turtle soup becoming particularly popular in Great Britain. Then new markets started to develop in Europe and Asia throughout the first half of the 20th century, peaking between the 1950s and the early 1970s.

Ongoing sea turtle consumption (legal and illegal) occurs in many parts of the world, including Australia, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, Central and South America, among many other nations. Apart from the meat, coastal communities may use internal organs such as kidney and liver for soup; oil extracted from the fat as a cure for respiratory problems, especially in children, while the blood can be drunk raw as a remedy for anaemia and asthma.

In the case of the hawksbill turtle, the richly patterned scutes that cover the carapace and plastron of the hawksbill (called tortoiseshell or bekko) have been considered a precious material — on par with ivory, rhinoceros horn, gold, and gems — for thousands of years; trade between some countries remains legal, and public sale of products, mainly for international tourists, occurs in many countries, legally and illegally. Read more about why hawksbill turtles are critically endangered.

References:

- Aguirre, A. A., Gardner, S. C., Marsh, J. C., Delgado, S. G., Limpus, C. J., & Nichols, W. J. (2006). Hazards associated with the consumption of sea turtle meat and eggs: a review for health care workers and the general public. EcoHealth, 3(3), 141-153.

- Humber, F., Godley, B. J., & Broderick, A. C. (2014). So excellent a fishe: a global overview of legal marine turtle fisheries. Diversity and Distributions, 20(5), 579-590.

- Mancini, A., & Koch, V. (2009). Sea turtle consumption and black market trade in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Endangered Species Research, 7(1), 1-10.

- Meylan, A. B., & Donnelly, M. (1999). Status justification for listing the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) as critically endangered on the 1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. Chelonian conservation and Biology, 3(2), 200-224.

Sea turtles are poikilothermic, meaning that they can not sufficiently internally maintain their internal body temperature and must absorb heat from the surrounding environment to maintain optimal body temperature. For this reason, they are particularly sensitive to ambient temperature and seek to occupy warmer waters, typically in the tropical and temperate zones and ideally over 20ºC. Exposed to temperatures below 10ºC, sea turtles may develop a condition called cold-stunned, a kind of hypothermia, if not treated.

References:

- Hochscheid, S., Bentivegna, F., & Speakman, J. R. (2002). Regional blood flow in sea turtles: implications for heat exchange in an aquatic ectotherm. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 75(1), 66-76.

- Schofield, G., Bishop, C. M., Katselidis, K. A., Dimopoulos, P., Pantis, J. D., & Hays, G. C. (2009). Microhabitat selection by sea turtles in a dynamic thermal marine environment. Journal of Animal Ecology, 78(1), 14-21.

Apart from the most obvious – swimming – sea turtles use their flippers for a variety of other things as well. During foraging, their flippers allow them to hold onto prey, swipe it aside to tear off bits or leverage against the substrate again to remove substantial parts of their food. Loggerhead and green turtles have also been observed to use the forelimbs to remove sediment – so essentially to dig up their food.

Additionally, sea turtles use their flippers during mating & nesting. Male turtles hold onto the carapace of the female by hooking on with a large claw on each forelimb. Female turtles move up the beach, pulling with the forelimbs and pushing with the hindflippers. They use the hindlimbs to dig a nest, which is later closed & covered/hidden with the use of all four extremities.

References:

- Fujii JA, McLeish D, Brooks AJ, Gaskell J & Van Houtan KS 2018. Limb-use by foraging marine turtles, an evolutionary perspective. PeerJ 6.

- Spotila JR & Tomillo PS (eds.) 2015. The Leatherback Turtle: Biology and Conservation. Johns Hopkins Press, Maryland, US.

- Wyneken, J. (1996). 7 Sea Turtle Locomotion: Mechanisms, Behavior. The biology of sea turtles, 1, 165.

Upon reaching maturity, most sea turtles travel long distances every few years for a breeding migration (from their feeding grounds to their breeding sites and back). These migrations can be hundreds or thousands of kilometers and take several months.

Leatherback turtles can travel 16,000 km (10,000 miles) or more each year, crossing the entire Pacific Ocean in search of jellyfish, while loggerheads have been tracked traveling from Japan to Baja, a distance of 13,000 km (8,000 miles). The longest recorded green turtle migration was 3,979 km (2,472 miles) from Chagos to Somalia.

In the Maldives, the sea turtles we observe on the reefs show extremely high site fidelity, meaning they do not, in general, move from reef to reef to find food but have a “home reef”.

Ghost Gear FAQ

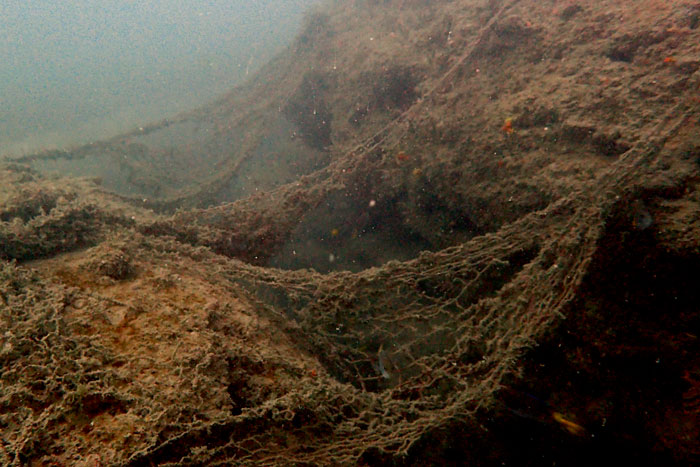

Wind and currents can cause ghost gear to drift far from its origin. Ghost gear can therefore end up in any type of marine habitat, including on beaches, coastal areas, harbours, coral reefs, and, of course, in both shallow and deep sea, causing an array of environmental and socio-economic issues:

Entanglement and entrapment of marine animals, often leading to severe injuries, including the amputation of limbs, and death.

Ghost fishing, a process in which abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear continues to catch and kill marine life.

Ingestion of fishing hooks, ghost nets and fishing lines by marine life and sea birds.

Smothering of coral reefs, damaging coral and even block access to necessary sunlight.

The dispersal of invasive species as microorganisms can accumulate on ghost gear overtime and ‘hitch-hike’ across ocean basins.

Devastation of shorelines and beaches, including sea turtle nesting beaches.

Ghost gear also poses a threat to boats and naval navigation, to divers, and to tourism by clogging up harbours and beaches around the world.

Ghost gear can be destructive regardless of its size or type. Even small fragments of broken gear can become a problem. Marine animals can ingest small pieces of ghost gear, whilst seabirds can incorporate fragments into their nests, posing risks of entanglement and ingestion to both breeding adults and their young. Indirectly, ghost gear also impacts livelihoods and fishing communities through the process of ghost fishing.

References

- O’Hanlon, N.J., Bond, A.L., Lavers, J.L., Masden, E.A. and James, N.A., 2019. Monitoring nest incorporation of anthropogenic debris by Northern Gannets across their range. Environmental Pollution, 255, p.113152.

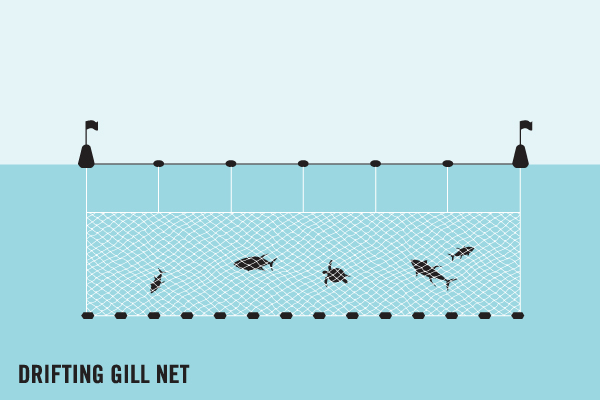

Ghost gear is fishing gear that has been abandoned, lost or discarded (ALDFG) at sea, in ports and at beaches. The term ‘ghost gear’ refers to all types of derelict fishing gear, whether that be nets, lines, traps and pots or fish aggregating devices (dFADs).

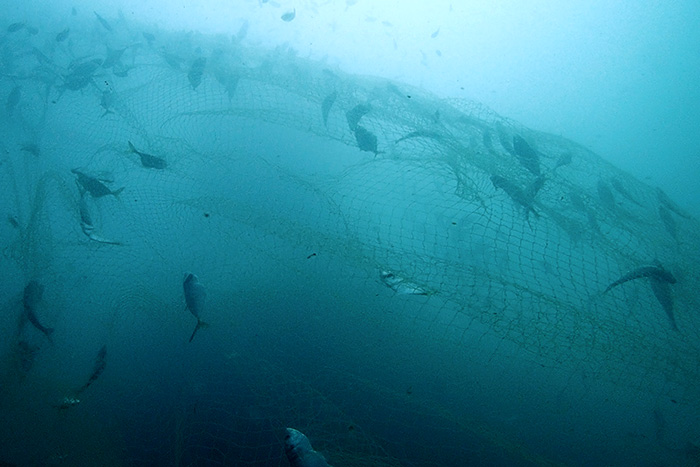

Ghost gear poses a grave threat to the marine environment, fishermen and local communities. Fishing gear is often targeted at one species or one group of species. However, when that gear becomes abandoned, lost or discarded, it does not discriminate. Whilst drifting with ocean currents, it will indeterminately catch and kill any marine life in its path. Consequently, ghost gear contributes to both the depletion of fish stocks around the world and the decline of many protected and endangered marine species.

Ghost gear take the form of a single net or line, or it may be a mixture of various materials. For example, some gear will drift with ocean currents and become entangled with other gear or marine debris, such as plastics, forming a conglomerate. These conglomerates can be particularly destructive due to their complex nature. Many marine species become entangled in these and, unfortunately, never make it out. In the Maldives, we often find olive ridley turtles with life-threatening injuries after being entangled in conglomerates of ghost gear, having likely been stuck there for months on end.

References

- Smolowitz, R.J., Corps, L.N. and Center, N.F., 1978. Lobster, Homarus americanus, trap design and ghost fishing. Marine Fisheries Review, 40(5-6), pp.2-8.

Neither bycatch nor ghost fishing are intentional actions, rather they are by-products of fishing. The most important difference between bycatch and ghost fishing is that one involves active fishing gear, and one does not.

Both bycatch and ghost fishing can cause life threatening injuries, and sometimes death, of non-target marine species. But it is important to define these different causes of fishing-related mortality, as the two issues require slightly different management strategies.

Bycatch

Bycatch is when fishing gear catches non-target animals whilst being controlled by the fishing industry. For example, purse seine fisheries often cast one large net around a school of fish (often tuna). Due to the size of the net, as well as catching the target species, it may also accidentally catch ‘non-target’ species, such as cetaceans, sharks and sea turtles.

Ghost Fishing

Ghost gear also catches and kills animals, but this happens despite the fishers no longer having operational control over the gear. For example, a fisher’s net may wash away or become dislodged during a storm. That lost net may then catch and kill marine life when drifting out in the open ocean, in a process called ghost fishing.

There are 4 key ways to tackle ghost gear:

- Reducing the amount of gear lost in the first instance

- Removing ghost gear from the ocean/beaches/harbours

- Recycling and repurposing of retrieved ghost gear

- Rescuing injured animals from ghost gear

When possible, all efforts should go into developing solutions that will prevent gear loss in the first instance.

Here are some specific examples of how different stakeholders can tackle ghost gear:

- Better transparency when reporting abandoned, lost or discarded fishing nets

- Better communication between fisheries to reduce conflict and subsequent gear loss

- Avoidance of superfine and easily breakable fishing nets

- Proper disposal of worn out fishing gear Making repairing nets common practice

- Taking responsibility for own gear e.g. gear marking so it can be traceable

- Actively reporting and removing gear when found

- Use of GPS topographic maps to reduce frequency of snagging incidents

- Better enforcement to reduce illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

- Be a part of a global effort. Ghost gear is a global issue so collaboration between governments is vital

- Banning or temporary closures of certain gear types, particularly in sensitive areas e.g. trawls, superfine gill nets, purse seine fisheries associated with drifting FADsHold responsible fisheries accountable

- Increase incentives for fishers to repair or recycle broken or worn out nets

- Increase incentives for fishers to bring back end of life fishing gear to port or beach side facilities

- Use of scientific research to inform decisions

- Use of more robust materials e.g. avoidance of superfine gill nets

- Implementing mitigation methods e.g. providing escape gaps in traps

- Implementing the use of biodegradable gear components into fishing gear design

- Continue to build baseline evidence e.g. where are the hotspots for ghost gear? How much ghost gear is there?

- Identify local/regional causes of gear loss e.g. through fisheries surveys

- Quantitatively assess the impact of ghost gear on marine life

- Reduce fish consumption if you are in the position to do so

- Make more conscious decisions when consuming fish e.g. actively avoiding fish caught by destructive fishing practices with high rates of gear loss

- Participate in clean ups e.g. beach cleans or ghost gear recovery whilst scuba diving

- Educate and spread awareness

‘Ghost gear’ probably got its name because of its cryptic nature and devastating effects. It can be can hard to see due to the gear itself – many fisheries opt for superfine, almost invisible, nets to increase their catch. It can be hard to find when it sinks into the deep sea and beyond our reach.

In addition, ghost gear, even though no one has control of it, continues to catch fish and other marine life. It is almost like it is being operated by a ghost crew of wind and currents.

Fishing gear becomes ghost gear when the fisher loses all operational control of the equipment. Gear loss can happen for various reasons, such as:

- Poor weather conditions

- Poor access to disposal or recycling facilities

- Lack of or inadequate gear maintenance

- High cost of retrieval

- Catch overload

- Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities

- Conflicts between fisheries

- Destructive fishing techniques.

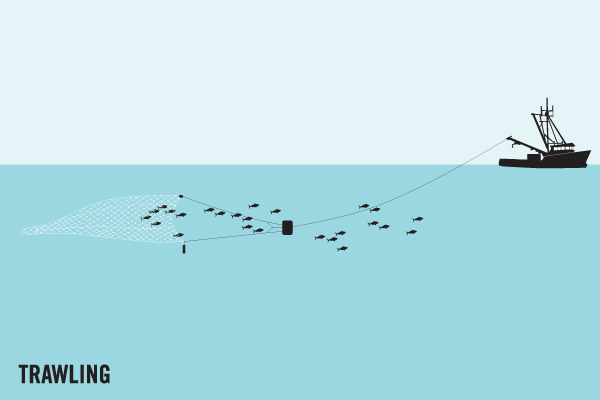

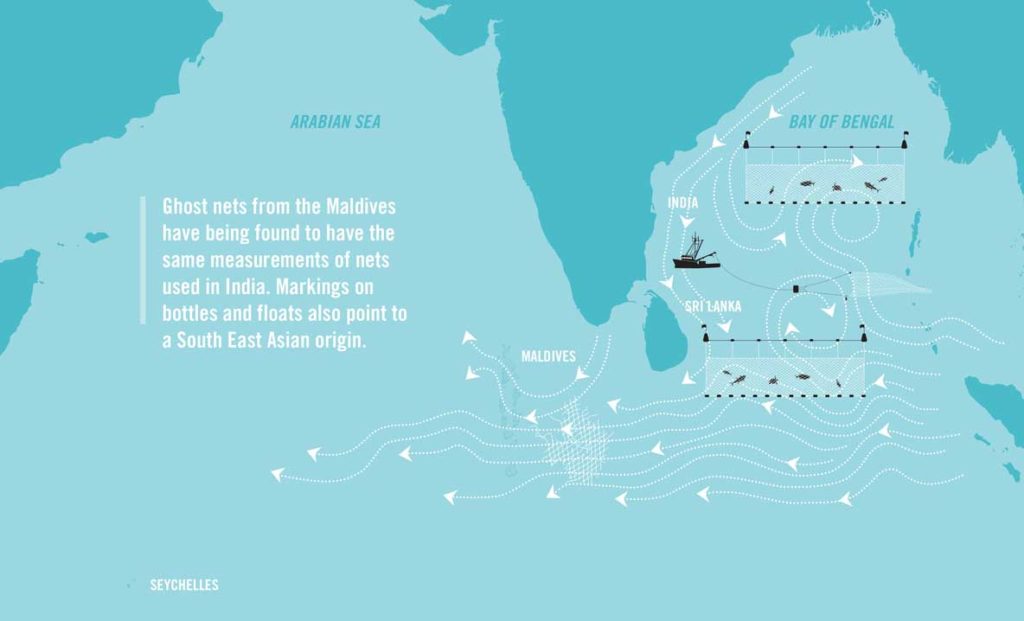

In Indian gillnet fisheries, for example, conflict between fisheries is the main cause of gear loss. Trawlers often drive straight through set gill nets, resulting in direct gear loss. This single net then has the capacity to smother an entire reef.

Another significant cause of gear loss is destructive fishing techniques. Bottom trawling, for example, involves dragging a huge net across the sea floor. During this method, fishing nets often snag on the bottom and break, leaving fragments of potentially entangling net behind. One example is in northern Australia, where trawl nets were the most abundant net type found stranded on beaches [4]. Similarly, trawl net fragments were one of the major gear types responsible for ghost gear found drifting into the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Maldives.

References

- Stelfox, M., Bulling, M. and Sweet, M., 2019. Untangling the origin of ghost gear within the Maldivian archipelago and its impact on olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) populations. Endangered Species Research, 40, pp.309-320.

- Thomas, S.N., Edwin, L., Chinnadurai, S., Harsha, K., Salagrama, V., Prakash, R., Prajith, K.K., Diei-Ouadi, Y., He, P. and Ward, A., 2020. Food and gear loss from selected gillnet and trammel net fisheries of India.

- Wilcox, C., Heathcote, G., Goldberg, J., Gunn, R., Peel, D. and Hardesty, B.D., 2015. Understanding the sources and effects of abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear on marine turtles in northern Australia. Conservation biology, 29(1), pp.198-206.

There is no simple answer to the question “how much ghost gear is in the ocean?”. In the 1970s it was estimated that 640,000 tonnes of ghost gear was produced each year, accounting for around 10% of ocean plastics. However, since ghost gear survey effort is often poor or sporadic, this is likely a gross under representation of the true amount of ghost gear in the ocean today. In Northern Australia alone, up to 3 tonnes of derelict nets have been reported per kilometre of coastline in a given year.

More research is needed to determine the current amount of ghost gear in our oceans today and to understand the effects that this is currently having on marine species at a population level. However, ghost gear is known to be cryptic and transboundary in nature. As a result, it can be extremely difficult to study.

References

- Gunn, R., Hardesty, B.D. and Butler, J., 2010. Tackling ‘ghost nets’: local solutions to a global issue in northern Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration, 11(2), pp.88-98.

- Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T. and Cappell, R., 2009. Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear.

- Wilcox, C., Hardesty, B.D., Sharples, R., Griffin, D.A., Lawson, T.J. and Gunn, R., 2013. Ghostnet impacts on globally threatened turtles, a spatial risk analysis for northern Australia. Conservation Letters, 6(4), pp.247-254.

Ghost gear can occur in any environment where fishing takes place but is not restricted to these areas. Ocean currents can cause ghost gear to drift far from its origin. As such, it can be found in all marine habitats around the world from coral reefs hundreds of thousands of miles away from their point of origin, to the deep sea at over 3,000m below the surface.

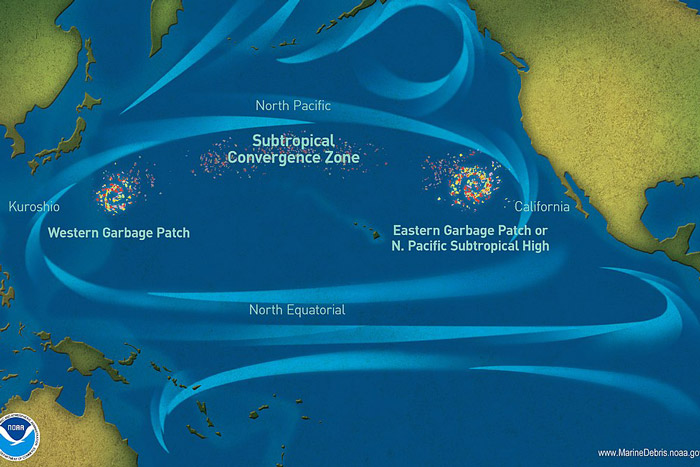

Ghost gear can also accumulate in certain areas. Many plastics, for example, accumulate in oceanic gyres. A study of the famous ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’ demonstrated that ghost nets alone represent 46% of the 79,000 tonnes of plastic observed.