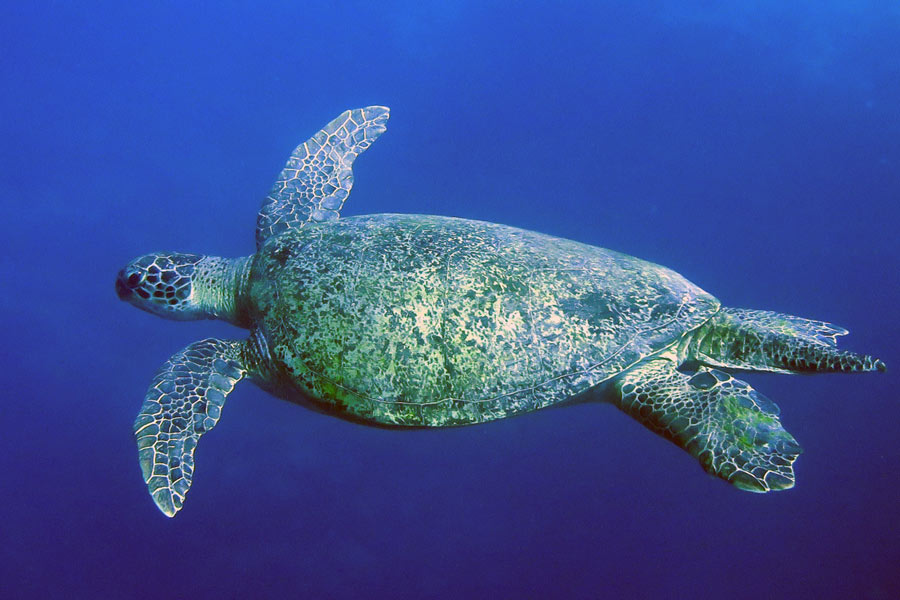

Green turtles (Chelonia mydas) are the largest of all the hard-shelled sea turtles. They can grow to about 134 cm in length and weigh between 135 and 250 kg as fully grown adults. The green turtle has a smooth, sub-circular to heart-shaped carapace with colour varying from greenish-yellow to greyish-brown. The plastron is yellowish-white in colour. In the Maldives, the colouration of adults is darker than that of green turtles in the western Indian Ocean.

Since the first assessment in the 1980s, green turtles had been listed as “Endangered” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species due to significant population declines in the past. Green turtles were hunted extensively for their shell, eggs and meat, threatening populations of the long-lived and slowly maturing species with extinction.

Thanks to global conservation efforts protecting sea turtle nesting beaches and reducing the impact of bycatch, the species was downlisted in October 2025 to the “Least Concern” category. While this spectacular success highlights the impact effective conservation measures can have, there are still regional subpopulations that are faring less well. The positive trajectory, however, gives hope for conservation of this enigmatic turtle species.

Green turtle biology and hehaviour

Green turtles may reach adulthood between 15 and 50 years of age. However, green turtles that eat a diet rich in nutrients grow and mature faster than those with a poor diet.

Mature females return to their nesting beaches once every 2-5 years to nest. Females migrate huge distances between feeding grounds and nesting areas, but tend to follow coastlines rather than cross open waters.

A female green turtle leaves a symmetrical track with a tail drag down the middle. Tracks are 85-90 cm across. The females lay between 1-6 clutches of between 70 and 125 eggs. Larger females tend to lay larger clutches of eggs. The incubation period lasts between 50 to 70 days.

Green turtle hatchlings measure around 50 mm long at birth. Their carapace is black and they have a light coloured plastron.

Green turtle diet

Adult green turtles are mostly considered to be vegetarians, feeding primarily on seagrasses and algae. The greenish coloured fat deposits under their carapaces is probably due to this diet, and the source of their name. Juvenile green turtles, however, feed on a more diverse diet which also features small crustaceans, soft corals, and jellyfish. As they mature, their diet shift from omnivorous to largely herbivorous.

When feeding on seagrass, green turtles actively select fresh green growth near the base of the grass. There is some evidence that green turtles actively farm certain areas of seagrass to ensure a steady supply of younger, protein-rich growth. When seagrass pastures are absent, they eat various species of red and green algae.

Green turtle habitat and distribution

The green turtle can be found worldwide in tropical and sub-tropical waters down to 20°C. They have been recorded as far north as the English Channel and as far south as Polla Island, Chile. Green turtles are highly migratory and as a result undertake complex migrations through drastically different habitats. Sometimes they migrate thousands of kilometres to lay their eggs.

Both males and females migrate from benthic foraging areas to mainland or island nesting beaches. The best feeding grounds rarely coincide with the best nesting beaches. Green turtles can travel 20-40 km per day when migrating.

Green turtles are not picky about their nesting beaches; sand size, composition, and the presence of beach vegetation do not seem to be factors in choosing a nesting site. Mating generally occurs around one kilometre offshore of nesting beaches.

Although nesting occurs in more than 80 countries worldwide, only 10-15 populations are of significant size (greater than 2,000 females yearly). The Indian Ocean is home to some of the largest nesting populations of green turtles in the world, particularly Oman, Pakistan, Reunion Island, and Yemen. The size of the nesting population of green turtles in the Maldives is currently unknown, but nesting is reported to happen all year-round.

Sea Turtles FAQ

Sea turtles can hold their breath for several hours, depending on their level of activity.

If they are sleeping, they can remain underwater for several hours. In cold water during winter, when they are effectively hibernating, they can hold their breath for up to 7 hours. This involves very little movement.

Although turtles can hold their breath for 45 minutes to one hour during routine activity, they normally dive for 4-5 minutes and surfaces to breathe for a few seconds in between dives.

However, a stressed turtle, entangled in a ghost net for instance, quickly uses up oxygen stored within its body and may drown within minutes if it cannot reach the surface.

Learn More About Sea Turtles – Free Online Courses

e-Turtle School – All about sea turtles

Everything you have ever wanted to know about sea turtles, from evolution to conservation. Suitable for all sea turtles lovers and those who want to learn more about these fascinating creatures.

Sea Turtle Science & Conservation

Deep dive into sea turtle science and conservation. Suitable for budding conservationists and those with an interest in the science surrounding turtles, their biology and conservation.

References:

- Hays GC, Akesson S, Broderick AC, Glen F, Godley BJ, Luschi P, Martin C, Metcalfe JD & Papi F 2001. The diving behaviour of green turtles undertaking oceanic migration to and from Ascension Island: dive durations, dive profiles and depth distribution. Journal of Experimental Biology 204: 4093-4098.

- Hays GC, Hochscheid S, Broderick AC, Godley BJ & Metcalfe JD 2000. Diving behaviour of green turtles: dive depth, dive duration and activity levels. Marine Ecology Progress Series 208: 297-298.

- Hochscheid S, Bentivegna F & Hays GC 2005. First records of dive durations for a hibernating sea turtle. Biology Letters 1: 82-86.

- Lutz PL and Musik JA (eds.) 1996. The Biology of Sea Turtles Volume I. CRC Press.

The actual documentation of a sea turtle’s age in the wild is difficult or nearly impossible. Individual turtles can be tracked for a shorter time of six month to three years with the help of satellite transmitters. Longterm studies rely on capture-recapture principle, just like our turtle photo id project. Each photo of a turtle represents a recapture event documenting that the individual is still alive.

A study of nesting green turtles in Hawaii observed female turtles returning to nest for up to 38 years after they were first identified. Assuming the average age at first nesting activity of 24 years, this would show that green turtles can live to up to at least 62 years.

Similar estimates have been made for loggerhead turtles.

References:

- Dodd C 1988. Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. Ecology 88.

- Humburg IH and Balazs GH 2014. Forty Years of Research: Recovery Records of Green Turtles Observed or Originally Tagged at French Frigate Shoals in Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, 1973-2013. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-PIFSC-40.

When sea turtles are juveniles, it is very difficult to tell their sex by eye as they do not differ externally. However, after reaching sexual maturity male sea turtles develop a long tail, which houses the reproductive organ. The tail may extend past the hind flippers.

Female turtles have a short tail, which generally doesn’t extend more than 10 cm (4 inches) past the edge of the carapace. Male sea turtles (except leatherbacks) have elongated, curved claws on their front flippers to help them grasp the female when mating.

The sex of a sea turtle embryo is determined by the temperature of the sand: warm temperatures result in more females while cooler temperatures result in more males.

The olive and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles are the smallest species, growing only to about 70 cm (just over 2 feet) in shell length and weighing up to 45 kg (100 lbs). Leatherbacks are the largest sea turtles. On average leatherbacks measure 1.5 – 2m (4-6 ft) long and weigh 300 – 500 kg (660 to 1,100 lbs). The largest leatherback ever recorded was 2,56 m (8.4 ft) long and weighed 916 kg (2,019 lbs) !

Kemp’s Ridley

55.6-66.0 cm carapace length, weight range of 25-54 kg for nesting females.

References:

- Marquez-M R 1994. Synopsis of Biological Data on the Kemp’s Ridley Turtle, Lepidochelys kempi (Garman, 1880). NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-343.

Olive Ridley

Curved carapace length 52.5-80.0 cm, weight less than 50 kg (average 35.7 kg) for nesting females.

References:

- Qureshi M 2006. Sea turtles in Pakistan. In: Shanker K and Choudhury BC (Eds.). Marine Turtles of the Indian Sub- continent. Heydarabad: India Universities Press, pp. 217–224.Reichart HA 1993.

- Reichart HA 1993. Synopsis of biological data on the olive ridley sea turtle Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz 1829) in the western Atlantic. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-336.

Hawksbills

Nesting females reported between 53.3 and 95.5 cm carapace length, with weight between 27.2 and 86.2 kg.

References:

- Witzell WN 1983. Synopsis of biological data on the hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766). No. 137. Food & Agriculture Org.

Green turtles

Nesting green females reported curved carapace length 75-134 cm, weight (after egg deposition) 45-250 kg (!).

References:

- Hirth HF 1997. Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Green Turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758). Vol. 2. Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior.

Flatbacks

Ones study (Ref. 1) found nesting females have a mean curved carapace length 86.3 cm, and mean weight of 67.4 kg. Another study (Ref. 2) found flatbacks to be between 87.5-96.5 cm.

References:

- Schäuble C, Kennett R and Winderlich S 2006. Flatback Turtle (Natator depressus) nesting at Field Island, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia, 1990-2001. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 5: 188-194.

- Limpus CJ 1971. The Flatback Turtle, Chelonia depressa Garman in Southeast Queensland, Australia. Herpetologica 27: 431-446.

Loggerheads

Adult loggerhead turtles measure between 65 and 115 cm in curved carapace length and typically weigh between 40 and 180 kg. The largest recorded loggerhead weighed 545 kg and measured 213 cm in presumed total body length. On average, nesting, and therefore adult, female loggerheads have a curved carapace length of 65.1-114.9 cm and weigh between 40.0 and 180.7 kg. Males fall into the same size range (79.0-104.0 cm curved carapace length).

References:

- Brongersma LD 1972. European Atlantic turtles. Zoologische Verhandlingen 121, Leiden.

- Dodd C 1988. Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle. Ecology 88: 1-119.

- Ernst CH and Lovich JE 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada, 2nd edition. John Hopkins University Press.

Leatherbacks

143.8-169.5 cm curved carapace length, weight 259-506 kg recorded for nesting females all around the world. Largest ever recorded specimen was found dead on a beach on the coast of Wales. The adult male turtle weighed 916 kg and its shell was 256.5 cm long. An autopsy revealed that it had drowned.

References:

- Eckert KL and Luginbuhl C 1988. Death of a Giant. Marine Turtle Newsletter 43: 2-3.

- Eckert KL, Wallace BP, Frazier JG, Eckert SA and Pritchard PCH 2012. Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Biological Technical Publication BTP-R4015-2012, US Fish & Wildlife Service.

Sea turtles cannot breathe underwater, however they can hold their breath for long periods of time. Sea turtles can hold their breath for several hours depending on their level of activity. For instance, a resting turtle can remain underwater for 4-7 hours whereas a foraging individual may need to surface more frequently.

When turtles hold their breath, their heart rate slows significantly to conserve oxygen – up to nine minutes may pass between heart beats! Despite this adaptation, a stressed turtle – such as one entangled in ghost net – will deplete oxygen stores rapidly and may drown within minutes if unable to reach the surface.

References:

- Long dive interval during hibernation: Hochscheid S, Bentivegna F & Hays GC 2005. First records of dive durations for a hibernating sea turtle. Biology Letters 1: 82-86.

- Dive duration during activity: Hays GC, Akesson S, Broderick AC, Glen F, Godley BJ, Luschi P, Martin C, Metcalfe JD & Papi F 2001. The diving behaviour of green turtles undertaking oceanic migration to and from Ascension Island: dive durations, dive profiles and depth distribution. Journal of Experimental Biology 204: 4093-4098.

- Hays GC, Hochscheid S, Broderick AC, Godley BJ & Metcalfe JD 2000. Diving behaviour of green turtles: dive depth, dive duration and activity levels. Marine Ecology Progress Series 208: 297-298.

Yes, sea turtles can feel it when you touch their shell. Sea turtle shells consist of bones, which are covered by a layer of so-called scutes (plates). These scutes are made of keratin, the same material that human fingernails are made of. There are nerve endings enervating even the bones of the shell. These nerve endings are sensitive to pressure, for example from a touch on the back.

References:

- Thomson JS 1932. The Anatomy of the Tortoise. Scientific Proceedings of the Royal Dublin Society.

- Zangerl R 1969. The turtle shell. In: Gans C and Bellairs A (eds.): The Biology of Reptilia, Vol. 1: 311-319. Academic Press, New York.

There is no way to determine the exact age of a sea turtle from its physical appearance other than to establish if it is a hatchling, juvenile or adult, depending on its size.

In the Indian Ocean, hawksbills and greens are smaller than their counterparts elsewhere. Good information on size at maturity does not exist for the northern Indian Ocean. It’s tricky to tell visually if an animal is mature or not, especially females: they can be big enough but not actually be sexually mature.

After it’s death, the age of a turtle can be determined by a technique called “skeletochronology”, whereby the humerus (arm bone) is examined. These bones reveal growth rings that allow the turtle’s age to be calculated, much like we can calculate the age of a tree.

References:

- Snover ML 2002. Growth and ontogeny of sea turtles using skeletochronology: methods, validation and application to conservation. PhD Thesis, Duke University, USA.

In the past 100 years, human demand for turtle meat, eggs, skin, and shells have reduced their populations. Destruction of feeding and nesting habitats and pollution of the world’s oceans are all taking a serious toll on the remaining sea turtle populations.

Many breeding populations have already disappeared, and some species are being threatened to extinction. The natural obstacles faced by young and adult sea turtles are staggering, but it is the increasing pressures from the presence of humans that are threatening their future survival.

Click to watch a short video about barnacles.

Barnacles are a highly specialized group of crustaceans. They have developed a sessile lifestyle as adults, attaching themselves to various substrates such as rocks, ships, whales or to sea turtles. Most commonly found barnacles on sea turtles belong to the genus Chelonibia, named after their host (Chelonia = turtle).

Initially, barnacles produce larvae. These early life stages are still mobile and facilitate further distribution. After the first six different so-called nauplius larvae, a seventh non-feeding larva develops: the cyprid. This is the stage which settles on a new substrate. The cyprid larvae has special attachment devices which allow it to hold onto the substrate, e.g. cup-shaped attachment organs on the antennae. Once settled, the barnacle develops into an adult and attaches in various ways: gripping the skin, cementing to the shell or boring into it.

Adult barnacles are filter feeders, thus benefit from a constant flow of water around them. As sessile creatures they can achieve that by a) settling in an area with pronounced water movement (e.g. close to shore) or b) settling on a moving substrate such as a sea turtle.

Even though barnacles are quite safely attached, barnacles actually are capable of moving as adults! They most likely achieve this through an extension of their cemented base as well as through muscle activity.

Most barnacles do not hurt sea turtles as they are only attached to the shell or skin on the outside. Others though burrow into the skin of the host and might cause discomfort and provide an open target area for following infections.

Excessive barnacle cover can be a sign of general bad health of a turtle. Usually sea turtles are debilitated first, and then become covered in an extensive amount of other organisms, such as barnacles and algae.

Luckily turtles are very resilient and can sometimes recover from such infestations.

Read more about Sea Turtle Hitchhikers – The Symbiotic Relationships of Sea Turtles here.

Learn More About Sea Turtles – Free Online Courses

e-Turtle School – All about sea turtles

Everything you have ever wanted to know about sea turtles, from evolution to conservation. Suitable for all sea turtles lovers and those who want to learn more about these fascinating creatures.

Sea Turtle Science & Conservation

Deep dive into sea turtle science and conservation. Suitable for budding conservationists and those with an interest in the science surrounding turtles, their biology and conservation.

References:

- Monroe R & Limpus CJ 1979. Barnacles on turtles in Queensland waters with descriptions of three new species. Memoires of the Queensland Museum 19: 197-223.

- Moriarty JE, Sachs JA & Jones K 2008. Directional Locomotion in a Turtle Barnacle, Chelonibia testudinaria, on Green Turtles, Chelonia mydas. Marine Turtle Newsletter 119: 1-4.

- Zardus, JD & Hadfield MG 2004. Larval development and complemental males in Chelonibia testudinaria, a barnacle commensal with sea turtles. Journal of Crustacean Biology 24: 409-421.

- Monroe R & Limpus CJ 1979. Barnacles on turtles in Queensland waters with descriptions of three new species. Memoires of the Queensland Museum 19: 197-223.Ross A & Frick MG 2007.

- From Hendrickson (1958) to Monroe & Limpus (1979) and Beyond: An Evaluation of the Turtle Barnacle Tubicinella cheloniae. Marine Turtle Newsletter 118: 2-5.

Sea turtles have many recognized roles in the evolution and maintenance of the structure and dynamics of marine ecosystems; they are an integral part of the interspecific interactions in marine ecosystems as prey, consumer, competitor, and host. They also serve as significant conduits of nutrient and energy transfer within and among ecosystems; and can also substantially modify the physical structure of marine ecosystems.

Sea turtles are an important part of the planet’s food web and play a vital role in maintaining the health of the world’s oceans. They regulate a variety of other organisms simply through eating them. For example, green turtles mainly feed on seagrass. By grazing on seagrass meadows, they prevent the grass from growing too long and suffocating on itself. Nice and healthy seagrass beds again perform a multitude of so-called ecosystem functions: they are a nursery ground for many marine species and additionally are an important carbon sink and oxygen provider in the ocean.

Another example are hawksbill turtles, who are mostly focused on eating sponges. Their sponge consumption is very important for a healthy coral reef by keeping the fast-growing sponges at bay and giving slower growing corals the chance to grow. Coral reefs are thought to be the most diverse ecosystem on the planet, providing habitats and shelter for thousands of marine organisms. Many fish spawn on the coral reefs and juvenile fish spend time there before heading out to deeper waters when they mature. Coral reefs also protect coastlines from wave action and storms and are an important revenue generator for many nations through tourism.

Leatherbacks eat jellyfish. Keeping the jellyfish population in check is important. Jellyfish prey on fish eggs and larvae and too many jellyfish means fewer fish.

Loggerheads feed on hard-shelled prey, such as crustaceans. By breaking up these shells, they increase the rate at which the shells disintegrate and, as a result, increase the rate of nutrient recycling in the ocean bottom ecosystems.

Sea turtles also provide habitat for many marine organisms! Barnacles, algae and small creatures called epibionts attach themselves to the turtle and by carrying these around, the sea turtles provide a food source for fish and shrimp. In fact, some fish species obtain their diet strictly from epibionts found on sea turtles.

Apart from that, sea turtles provide an important food source for other organisms, especially in their early life stages. Ants, crabs, rats, raccoons, foxes, coyotes, feral cats, dogs, mongoose and vultures are known to dig up unhatched turtle eggs; the eggs are a nutrient-rich source of food. Juvenile turtles are a food source for various sea birds, fish and invertebrates. Adult sea turtles are preyed upon by sharks and killer whales.

Unhatched eggs and empty eggshells remaining inside nests on the beaches are a fertilizer for beach vegetation – they provide nutrition for plant growth with helps stabilize the shoreline as well as provide food for a variety of plant eating animals.

Because sea turtles can migrate huge distances, they also play an important role in generating and maintaining diversity throughout the world’s oceans by transporting the organisms that live on them to and from reefs, seagrass beds and the open ocean.

References:

- Bjorndal, K. A., & Jackson, J. B. (2002). 10 Roles of sea turtles in marine ecosystems: reconstructing the past. The biology of sea turtles, 2, 259.

- León, Y. M., & Bjorndal, K. A. (2002). Selective feeding in the hawksbill turtle, an important predator in coral reef ecosystems. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 245, 249-258.

References

- Bjorndal KA, Wetherall JA, Bolten AB and Mortimer JA 1999. Twenty-Six Years of Green Turtle Nesting at Tortuguero, Costa Rica: An Encouraging Trend. Conservation Biology 13: 126-134.

- Hirth HF 1997. Synopsis of the Biological Data on the Green Turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758). Vol 2. Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior.

- Hudgins J, Mancini A and Ali K 2017. Marine turtles of the Maldives – A Field Identification Guide. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN and Government of Maldives. 90 pp.

- Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission. Guidelines for Marine Turtle Permit Holders: Nesting Beach Surveys: Crawl Identification Guide. 2014.

- Moran KL and Bjorndal KA 2007. Simulated green turtle grazing affects nutrient composition of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum. Marine Biology 150: 1083-1092.

- Wallace, B.P. & Broderick, A.C. 2025. Chelonia mydas. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: e.T4615A285108125. Accessed on 10 October 2025.