Ghost nets are fishing nets that have been abandoned, lost or discarded (ALD), at sea, on beaches or in harbours. They are a major contributor to the bigger problem of ghost gear, which refers to all types of fishing gear, including nets, lines, traps, pots and fish aggregating devices (FADs), that are no longer actively managed by fishers or fisheries.

Each year, ghost gear is responsible for trapping and killing a significant number of marine animals, such as sharks, rays, bony fish, sea turtles, dolphins, whales, crustaceans and sea birds. They can cause further destruction by smothering coral reefs, devastating shorelines, and damaging boats.

How does fishing gear become ghost gear?

Ghost gear is an unintended byproduct of fishing and occurs when the fisher loses all operational control of the equipment. Here are some reasons why fishing gear may become abandoned, lost or discarded:

Ghost gear is a global issue. It can occur anywhere in the world where fishing occurs, and hundreds of thousands of miles beyond that too. Ocean currents can cause ghost gear to drift far from its origin and cross countless borders. As a result, the gear can often end up all over the world on beaches, coral reefs, in the deep sea and in the open ocean as large conglomerates.

Due to its cryptic and transboundary nature, it is extremely difficult to assess the impact of ghost gear on the environment, but it is widely recognised as a major source of mortality for many marine organisms.

Ghost gear and marine life

Ghost fishing

Ghost gear, and specifically ghost nets, can cause harm to marine life by continuing to fish in a process called ‘ghost fishing’, causing entanglements of, and ingestion by, marine life.

Entanglement in hhost Nets

Through this process of ghost fishing, ghost gear can entangle all sorts of marine life, including sharks, rays, manatees, bony fish, sea turtles, dolphins, whales, crustaceans, and sea birds. These animals can remain stuck in nets for weeks, months or even years. As a result they are often found with life threatening injuries – if they haven’t already suffered or died from exhaustion, starvation or predation.

Ingestion of fishing hooks, ghost nets, and fishing lines

Entanglements are not the only problem caused by ghost fishing. Marine animals often ingest hooks, lines and nets, causing an array of problems such as perforation of the gastrointestinal tract, obstruction, sepsis, toxicity and starvation.

Smothering of coral reefs

Ghost nets often sink to the sea floor and can be found in sensitive habitats, such as coral reefs. Here, the ghost nets can damage coral and even block access to necessary sunlight by smothering the reef. Coral reefs play a vital role in a healthy ocean ecosystem.

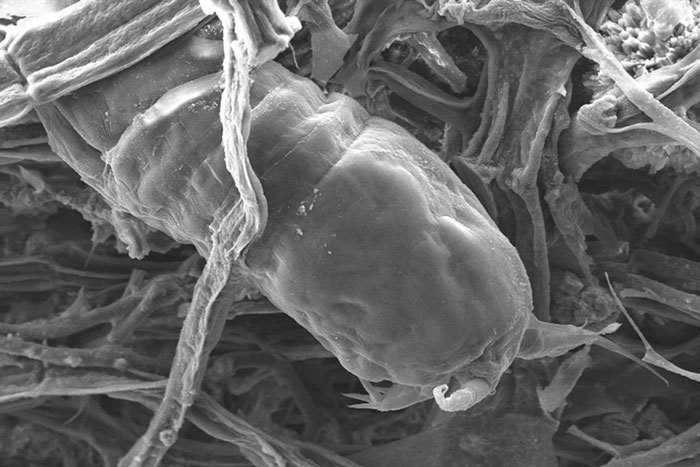

Invasive species dispersal

Ghost nets can travel for thousands of miles and occupy a variety of different habitats. But often, they are not alone! Microorganisms often accumulate on ghost gear overtime and ‘hitch-hike’ across ocean basins. This can encourage an accelerated dispersal of invasive species, which can in turn endanger other species, increase the occurrence of disease and parasites, and potentially disrupt entire marine ecosystems.

Ghost gear and sea turtles

Nesting grounds

On nesting beaches, ghost gear may act as obstacles for both nesting females and her hatchlings. Female turtles can become entangled in marine debris on the beach when nesting, meanwhile hatchlings can struggle to navigate their way to the sea in the presence of ghost gear (even in very small quantities).

Foraging grounds

Sea turtle foraging habitats include seagrass beds and coral reefs, which are often close to shore. As such, they’re often the first place nets are discarded or pots and traps are lost. Ghost nets in particular can smother coral reefs and be hard to detect, so will often entangle sea turtles.

Open ocean

Sea turtles, whether adult, juvenile or hatchling, can often become entangled in ghost gear in the open ocean. Sea turtles make huge migrations between their nesting and foraging grounds and some species spend a lot of their time in the open ocean. Ghost gear can be mistaken for floating algal mats, which sea turtles use for shelter and food. For this reason, sea turtles often get entangled in that gear and can sustain life-threatening injuries as a result.

It is thought that of the 7 species of sea turtle, 2 are of particular concern when it comes to entanglements in the open ocean. The leatherback and olive ridley sea turtles have a pelagic nature, meaning they spend most of their lives in the open ocean. As a result, they have a high chance of encountering floating ghost gear.

ORP’s work to tackle ghost nets and ghost gear in general

Ghost gear is a global issue. Large-scale commercial fisheries fishing in international waters produce the vast majority of derelict gear. Consequently, the issue requires engagement on a local, national and international scale in order to create change.

The Olive Ridley Project works at various levels to tackle the issue of ghost gear, from ghost gear retrieval and educating fishers to influencing local and international policy makers.

We sit on several working groups within the NGO Tuna Forum, guiding the group on the ghost gear issue to better manage the world’s tuna fisheries. Our partnership with IPLNF to collect and upcycle ghost gear in the Maldives won the Joanna Toole Ghost Gear Solutions Award. In addition, we focus on, and encourage, collaboration between NGOs, research institutes and governments around the world.

The ultimate goal of our research is to provide recommendations on how to manage and mitigate the ghost gear issue. We also hope that our research results will prompt changes in fishing net and gear designs, as well as influence fishing legislation.

Though ORP works in various ways to combat ghost gear, it is important to stress that preventative measures are preferred in order to stop the accumulation of ghost gear in our oceans. For example, developing solutions to prevent gear loss in the first place would be far more sustainable in the long term than costly clean up operations.

Since the project started in 2013, we have:

- Actively removed more than 14.3 tonnes of ghost gear

- Recorded over 1,000 sea turtle entanglements

- Rescued and treated more than 250 injured sea turtles (more than 60% of whom were victims of ghost gear and other marine debris)

- Successfully released more than 150 rehabilitated sea turtles back into the wild

- Educated fishing and diving communities in Pakistan and Kenya on how best to retrieve ghost gear from the ocean safely

- Found innovative ways to repurpose ghost nets

Find out more about ORP’s work to combat ghost gear and its effect on sea turtles:

In the field:

- Ghost Gear Retrieval

- Repurposing Ghost Gear: Ghost Leashes

- Conservation medicine

References

- McCauley, S.J. and Bjorndal, K.A., 1999. Conservation implications of dietary dilution from debris ingestion: sublethal effects in post‐hatchling loggerhead sea turtles. Conservation biology, 13(4), pp.925-929.

- Richardson, K., Asmutis-Silvia, R., Drinkwin, J., Gilardi, K.V., Giskes, I., Jones, G., O’Brien, K., Pragnell-Raasch, H., Ludwig, L., Antonelis, K. and Barco, S., 2019. Building evidence around ghost gear: Global trends and analysis for sustainable solutions at scale. Marine pollution bulletin, 138, pp.222-229.

- Stelfox, M.R., 2021. The cryptic and transboundary nature of ghost gear in the Maldivian Archipelago. University of Derby (United Kingdom).

- Stelfox, M., Burian, A., Shanker, K., Rees, A.F., Jean, C., Willson, M.S., Manik, N.A. and Sweet, M., 2020. Tracing the origin of olive ridley turtles entangled in ghost nets in the Maldives: A phylogeographic assessment of populations at risk. Biological Conservation, 245, p.108499.

- van der Hoop, J., Barco, S.G., Costidis, A.M., Gulland, F.M., Jepson, P.D., Moore, K.T., Raverty, S. and McLellan, W.A., 2013. Criteria and case definitions for serious injury and death of pinnipeds and cetaceans caused by anthropogenic trauma. Diseases of aquatic organisms, 103(3), pp.229-264.

- Zabka, T.S., Haulena, M., Puschner, B., Gulland, F.M., Conrad, P.A. and Lowenstine, L.J., 2006. Acute lead toxicosis in a harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardsi) consequent to ingestion of a lead fishing sinker. Journal of wildlife diseases, 42(3), pp.651-657.