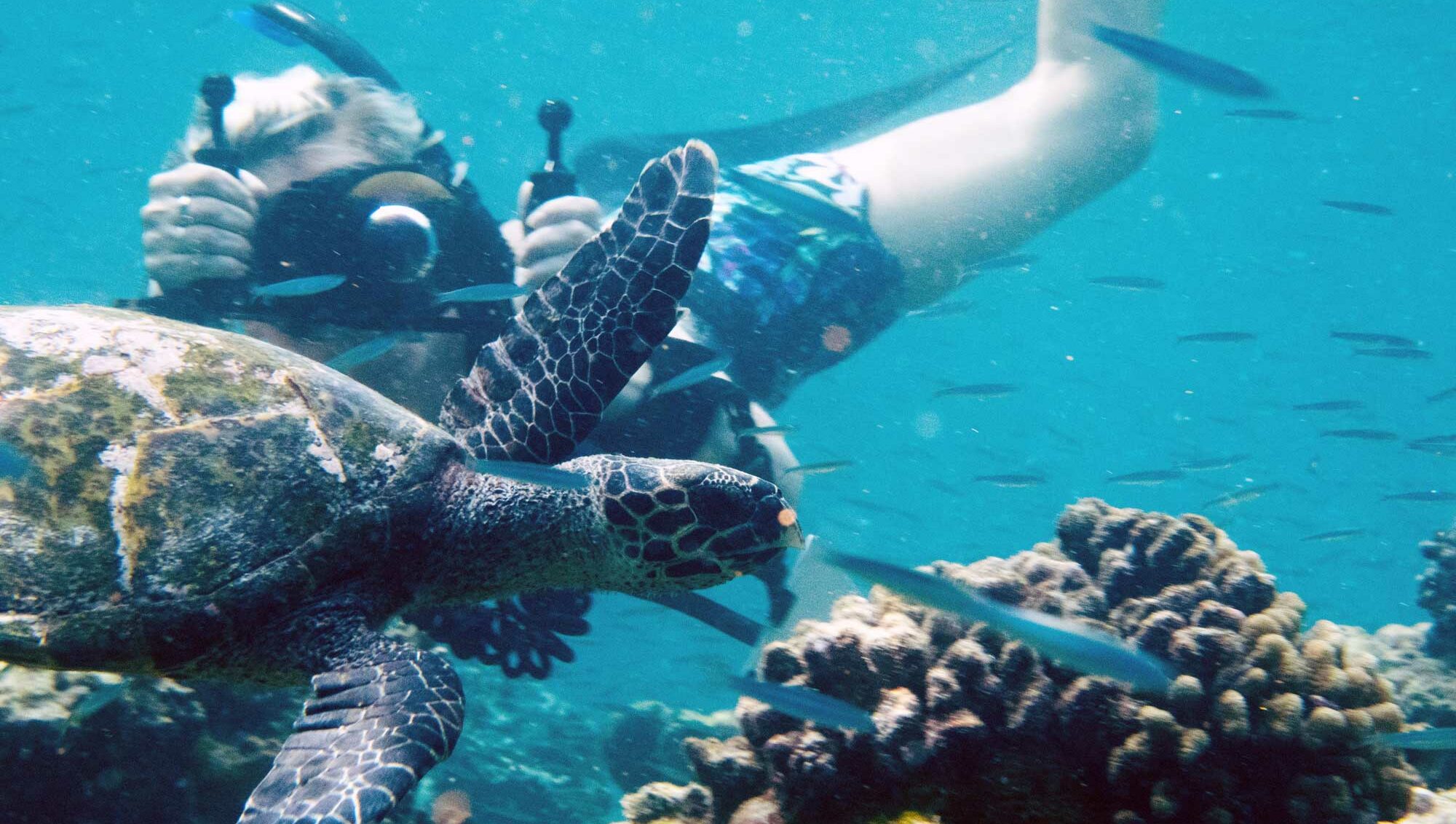

Photo-ID is a non-invasive technique used to identify individual animals in a population – and track them over time – from natural marks on their body. For sea turtles, it relies on capturing photographs of the unique patterns of scales on the animal’s face. Photo-ID can be used as an alternative to tagging, where data is analysed through Capture-Mark-Recapture (CMR) methods. Data collection for photo-ID involves no handling or harassment of animals and causes no harm to animals.

Why identify individual sea turtles?

All seven species of sea turtles have been impacted by human actions, with populations having faced severe declines up to the threat of extinction. To create effective conservation strategies to prevent this from happening, we need to be able to protect sea turtles and their habitats. Therefore, we first need to know the status quo – how many turtles are there in our area of interest and how are these populations developing over time? To do that we need reliable information on population structure, distribution, habitat use and migration patterns of all sea turtle species.

The starting point for ecological and conservation studies is often the ability to identify individuals. This allows us to make accurate estimates of population size and then we can use statistical modelling to reveal patterns of residency and movement of turtles between reefs. It can thus help determine the population and population structure of a reef at a given time and, for example, allows us to calculate inter-nesting periods and analyse how stable a local population is.

The difficulty of studying sea turtles

Sea turtles spend most of their life at sea. In addition, they are truly global citizens, crossing oceans, feeding and nesting on the shores of many different countries. All these factors combined with their migratory nature make them rather difficult to study. Yet, although there are many things we do not know about turtles, years of research have provided insights into daily activities and behaviours such as feeding, courtship, mating and nesting.

Most sea turtle research and conservation efforts happen on nesting beaches because they are more easily accessible than the open ocean. Nesting beaches are extremely important to the survival of sea turtles. However, sea turtles spend most of their life in the water. And what they do, where they go, and the threats they face in the ocean, are still not fully understood or documented.

Photo-ID: “Capture-Mark-Recapture”

Traditionally, researchers, in order to monitor sea turtle populations, have used standard marking techniques for capture-mark-recapture (CMR) studies, such as flipper tagging, with either external or internal tags. Tagging, however, is costly and can cause stress to the turtle.

Furthermore, tags seldom stay attached for a lifetime and are also difficult to apply, thus limiting the number of deployed tags as well as the participation of untrained volunteers and citizen scientists in such studies.

Photo-ID, however, is a cost-effective, non-invasive technique that makes it easy to monitor sea turtles without disturbing them. It is also a scientifically proven method of “tagging” animals.

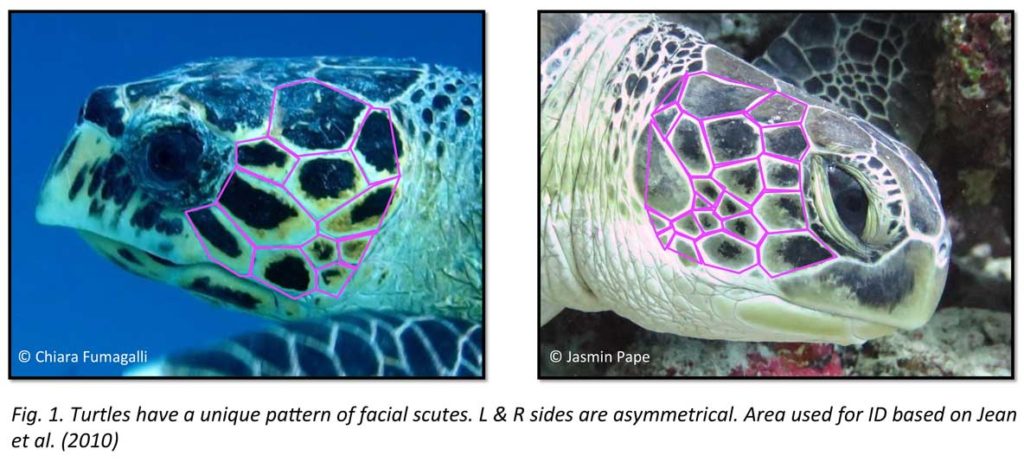

This method identifies individual turtles by comparing their scale patterns on the animals head, and has been shown to be more effective than tagging in 2008 by Reisser et al. A sea turtle’s facial scales are unique, like a fingerprint, and stay the same over time. Photo-ID is rapidly becoming an effective tool for

marine turtle populations, which is applied all over the world from Brazil to Reunion and Malaysia. It is also a great way to involve citizen scientists – that is members of the general public.

Interestingly, recent studies have also investigated the potential of using scale patterns on the sea turtles’ flippers for identification. This method is easy to apply on static animals in a rescue setting, but is more challenging for observations in the wild, especially underwater.

The Internet of Turtles (IoT)

As of June 2025, the Olive Ridley Project has identified 5,224 unique hawksbills and 1,759 greens, and logged 42,05 sightings of sea turtles, in the Maldives.

In Kenya, we have identified 896 individual hawksbills and 749 greens, and logged 4,568 sightings

In Oman, we have identified 910 hawksbills and 219 green turtles, and logged 1,028 sightings.

In Seychelles, we have identified 253 hawksbills and 11 green turtles, and logged 616 sea turtle sightings.

In Pakistan, we have identified 13 green turtles on 13 occasions.

Each month we add hundreds of new sightings to our database – one of the largest sea turtle datasets in the world.

We use theInternet of Turtles (IoT) platform to analyse and document all identified sea turtle sightings. This conservation tool has the potential to greatly improve and facilitate data collection for sea turtles by using Photo-ID data. The IoT platform combines data analytics with individual animal tracking. IoT uses computer vision to compare new IDs to the existing database, and Wildbook to store metadata. This not only supports our ID process but also facilitates Photo-ID comparisons across larger geographic scales.

This global-scale database of sea turtle information helps researchers identify the most important sea turtle aggregation areas in need of protection, and the highest priority conservation actions. In addition, it will enable researchers to measure the effectiveness of conservation efforts by following population trends, and inform strategic conservation decisions world wide.

Submit sea turtle Photo-ID images as a citizen scientist

You can contribute to this vital research as a citizen scientist. Send us your sea turtle photos from Maldives, Kenya, Oman and Seychelles.

To make a sea turtle ID, we need:

- One clear image of the left side of the sea turtle’s face

- One clear image of the right side of the sea turtle’s face

- Specific location information (ideally GPS coordinates)

- Date and time of the sighting(s)

- Your name

If you have images of the full shell and/or the top of the head, we would like those too.

For the Maldives, Seychelles, Oman, please send your images by email to seaturtleid@oliveridleyproject.org.

For Kenya, please send your images by email to dianibeach@oliveridleyproject.org.

If you are based in Kenya, the Maldives, Oman, or the Seychelles and would like to become a regular contributor, please contact us on seaturtleid@oliveridleyproject.org.

Associated publications and references:

- Gatto, C.R., Rotger, A., Robinson, N.J. and Tomillo, P.S., 2018. A novel method for photo-identification of sea turtles using scale patterns on the front flippers. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 506, pp.18-24.

- Jean, C., Ciccione, S., Talma, E., Ballorain, K. and Bourjea, J., 2010. Photo-identification method for green and hawksbill turtles-First results from Reunion. Indian ocean turtle Newsletter, (11), pp.8-12.

- Reisser, J., Proietti, M., Kinas, P. and Sazima, I., 2008. Photographic identification of sea turtles: method description and validation, with an estimation of tag loss. Endangered Species Research, 5(1), pp.73-82.Jean et al. 2010

- Mills, S.K., Rotger, A., Brooks, A.M., Paladino, F.V. and Robinson, N.J., 2023. Photo identification for sea turtles: Flipper scales more accurate than head scales using APHIS. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 566, p.151923

To read our published scientific Photo-ID research, click here.