Understanding a species’ reproductive biology is a vital part of understanding its life cycle. Basic characteristics include fertility, fecundity, mating system, nest site selection and behaviour, sex ratio and the number of offspring produced.

Nesting Research

Sea turtles lay multiple clutches of eggs per nesting season on beaches all around the world. This is for the most part the only time they spend on land and also the time when they are most easily accessible for scientists to study them and gain insight into the sea turtle population.

Nesting research is a crucial component of sea turtle conservation. Nevertheless, there are still many open questions when it comes to sea turtle nesting worldwide.

Our aim is to understand all vital aspects of sea turtle nesting in each country we study, including remigration intervals, inter-nesting intervals, hatching success rates and nesting seasonality, and to support the establishment of conservation measures on the basis of our research.

Data collection

ORP is collecting data on sea turtle nesting in the Maldives mainly from Baa, Laamu, Lhaviyani, Noonu, North Malé and Raa atolls, where ORP’s Sea Turtle Biologists and Veterinary Teams monitor the nests.

We are encouraging other biologists in the country to report any nesting incidences as well, and support respective initiatives for example from South Malé or Haa Daalhu Atoll.

Additionally, ORP is monitoring sea turtle nesting on Félicité Island in Seychelles, investigating the same general questions regarding sea turtle nesting and thus providing a basis for the identification of regional and national similarities and differences.

ORP conducts sea turtle nest and nesting beach monitoring in the Maldives with a special permit from the Environmental Protection Agency of the Maldives, and in the Seychelles with a permit from the Seychelles Bureau of Standards.

Nesting Activity

The documentation of nesting activity throughout each country will help us identify specific nesting seasons in each region. These might not be uniform in all atolls and countries, resulting in the requirement of different protection measures adapted to local seasonality.

The use of photo identification of females coming to shore helps us identify individual animals and thus investigate remigration intervals and the precision of natal homing in sea turtles.

We are documenting how often each individual turtle comes to nest per season and how long she takes between individual clutches and nesting seasons. Since turtles do not reproduce every consecutive year, but can take between two and six years for the so-called remigration interval, it is important to know the predominant time between nesting activity to evaluate the overall productivity of a population and its potential for growth.

Although nest counts alone cannot provide a direct measure of the size of a population, overall nesting activity can be used as a proxy to infer general population trends.

Nest Monitoring

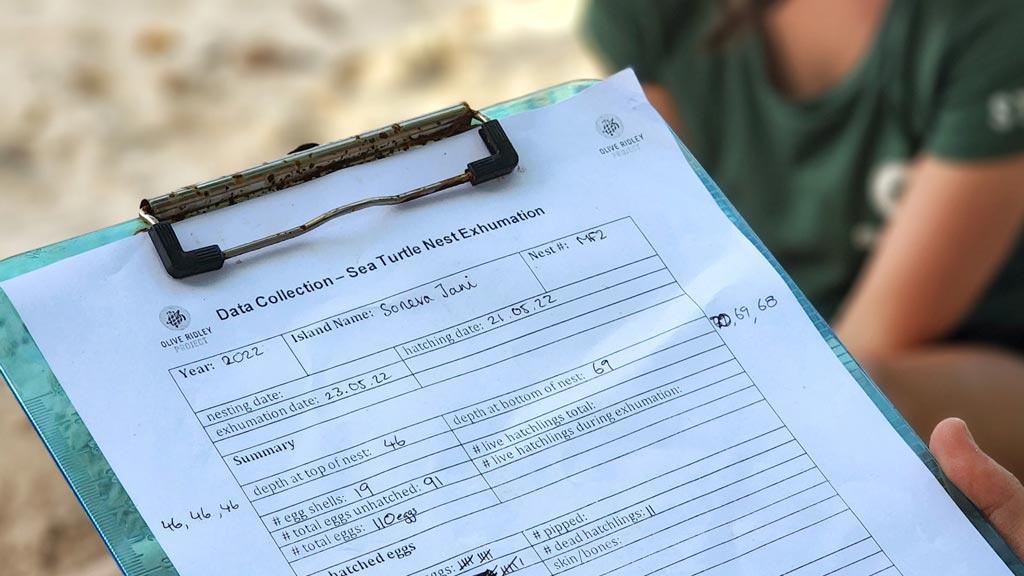

After each nest is laid, we monitor it until hatching to study incubation time and we also analyse nest contents after hatching to determine clutch size and hatching success rates, and document any developmental abnormalities in embryos and hatchlings still in the nest.These studies can again provide invaluable indications as to the future success or decline of nesting sea turtle populations.

Together with nesting beach parameters, such as nest position on the beach and temperature inside the nest, the nest content analysis will help us understand the suitability of each region’s beaches for sea turtle development and each species’ potential to adapt to a changing environment.

Along with our partners in Laamu Atoll, we have a special eye on Gaadhoo island, which is historically home to the most important nesting beach in the Maldives for green turtles. Available historic data is sporadic, but together with data from recent nest monitoring efforts show a drastic decline in nesting activity on Gaadhoo in the last 35 years.

This is potentially indicating a decline in overall turtle populations throughout the country and can be used as a basis to develop and implement effective protective measures. As shown by ORP led beach surveys since 2018, illegal take activity poses a considerable threat to turtle nests on uninhabited islands such as Gaadhoo, but might be reduced through regular beach patrols.

Nest Site Selection & Nest Location

Sea turtles have a large area of coastline to choose from when it comes to potential nesting sites, but not every coast and beach is equally suitable for successful turtle development. While different turtle species can have different preferences, most commonly they nest on sandy beaches in tropical and subtropical regions.

ORP is documenting the characteristics of nesting beaches and where exactly the turtles tend to lay their eggs, including distance from the high tide line, proximity to vegetation and the overall GPS location of each nest.

This has very important conservation management implications for recommendations regarding land use around turtle nesting beaches, as well as for areas with a shifting beach topology due to sand accumulation and beach erosion. We are working together with local stakeholders to develop and support sustainable conservation measures.

Incubation Period

A very important factor influencing the success of sea turtle nests is the temperature within the nest during incubation. There is an optimum temperature range at which sea turtle eggs develop successfully, which is between 27 and 31 °C. Temperatures outside of that range lead to increased death of embryos up to a total failure of each clutch.

Additionally, the temperature during incubation will lead to faster or slower development, with lower temperatures being associated with incubation times of up to 80 days. Depending on the incubation time, hatchlings can differ in size at the time of hatching, which can lead to differences in fitness. Those factors are not fully understood yet and will be a direction for future research.

Most importantly though the incubation temperature influences the sex of the hatchlings. Sea turtles are one example for reptiles showing temperature dependent sex determation. At higher temperatures, turtle embryos are more likely to become female, while at lower temperatures they are more likely to be males. The closer a temperature is towards to edge of the tolerance level, the higher the likelihood of only one sex developing within a nest. A rise in nesting beach temperatures in many places worldwide due to climate change has been shown to result in a skewed sex ratio endangering the reproductive potential of a population.

In a pilot project in Laamu Atoll, Maldives, ORP is collecting data on nesting beach temperatures evaluating the current situation in the country for the first time. We will also start

Publications

Köhnk, S., Brown, R. & Liddell, A. (2021):

‘Finding of a two-headed green turtle embryo during nest monitoring in Baa Atoll, Maldives‘.

Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 88(1), a1940, https://doi.org/10.4102/ojvr.v88i1.1940

A detailed account of the discovery of a two-headed, partially developed green sea turtle embryo. The embryo was found while researching the nesting activity of sea turtles on an island in Baa atoll, Maldives. The article shows the importance of monitoring nesting activities as a basis for conservation.