We carry out nest excavations to determine how many eggs were laid in a nest, and how many of these successfully hatched and if those hatchlings have managed to emerge from the nest. This helps us to identify environmental conditions which might impact nests, leading to a reduced number of hatchlings, and it informs conservation efforts and the protection of future clutches. On this occasion, when we gently opened an unhatched egg, we found a fully formed embryo with two heads inside!

Polycephaly – having more than one head

The technical term for this malformation is ‘polycephaly’. In this case, it was two heads joined in the centre, with an adjoined eyelid. The embryo had two fully formed beaks but shared a neck. In figure 2 you can see the embryo removed from its egg and uncurled. Compare this with the normal hatchling in an uncurled position in Figure 3.

In Figure 2, you can also see the prominent yolk sac in the middle of the turtle’s belly area – this gets absorbed into the abdomen after the turtle has hatched but before it emerges out of the nest. The yolk sac provides sea turtle hatchlings with nutrients and energy for their long journey ahead!

How often and why does polycephaly occur?

Polycephaly is a very rare birth defect and one we haven’t seen during any of our nest surveys in the Maldives until this embryo was found. There are isolated anecdotal reports of two-headed sea turtle embryos and hatchlings from around the world, with an increasing number of systematic reviews on the topic of these and other malformations published in scientific outlets throughout the years.

Overall, malformations such as polycephaly have been recorded to affect less than 2% of all eggs laid during a nesting season in certain populations in the Americas or Australia, but this might vary for other less well documented populations.

However, concrete data of the prevalence is hard to come by. Reptiles are more commonly found with polycephaly than other animals but it is still very unusual.

As for the ‘why’, polycephaly occurs due to either one embryo that incompletely splits, or two embryos that incompletely fuse, early during development. (Figure 4). This can cause a number of other abnormalities, such as extra organs, incompletely fused parts of the body or even the absence of some body parts or organs.

What was the two-headed turtle embryo’s anatomy?

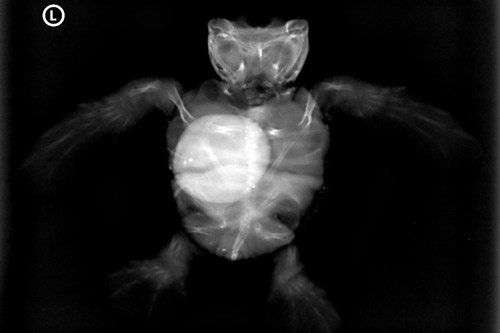

Sea Turtle Veterinary Surgeon, Dr. Minnie took X-rays of the embryo to have a peek at its bones and shell. We weren’t looking for anything in particular, but it was very interesting to see what the embryo’s anatomy looked like.

Figure 6, 7 and 8 show their X-rays from 3 angles, first from from the side, second from above with the embryo resting on its front, and then third on its back. It is hard to see fine detail due to the embryo’s tiny size, but we can see where the spine of its neck divides into two. Plus we can make out the bones of its limbs very well, including the bits that are tucked within its shell, such as the shoulder bones. The bright white circular structure in the middle is the yolk sac, which shows up well on X-rays due to its density.

Why didn’t this two-headed embryo survive?

Although there are examples of living polycephalic animals such as snakes and tortoises, it is a problematic malformation. Dr. Minnie believes this embryo didn’t make it due to the malformation also affecting its brain and spinal cord development. There was a little area on the back of its neck where the tissues hadn’t formed properly. It also had a malformed carapace near its neck, so this was all likely part of the same problem.

However, the embryo had a totally normal set of organs, along with one windpipe that split into two, one for each head, and the same for the oesophagus. And although the two heads shared a central eyelid, they each had a normal pair of eyes. (Figure 9 shows their joined eyelids).

Hatchling survival rates

Even if this embryo had survived to hatching point, it is highly unlikely that it would have lived due to the difficulty it would have had feeding with two mouths. However, that is sometimes the way it goes in the natural world. The survival of sea turtle hatchlings is already naturally very low; with estimates giving only one in one thousand sea turtle hatchlings a chance to survive until adulthood. When natural ecosystems are balanced, this is not a concern for sea turtle populations – it is the way they have been doing things for 110 million years! It is when human threats such as climate change, beach development or fishing nets, place additional pressure on the survival of hatchlings, we see even greater problems with falling sea turtle populations.

It was certainly a very interesting learning experience for all involved and makes for a very interesting look into the wonders, and sometimes mistakes, of nature.

To read a more detailed account of this discovery of a two-headed, partially developed, green sea turtle embryo, read this research paper on the subject.

Further insights

Following this initial discovery, the ORP team has continued nest excavations throughout the country, and recorded more embryos and hatchlings with a variety of abnormalities such as polycephaly.

Besides other embryos with multiple heads, we have also observed hatchlings with incompletely developed eyes, missing coloration or additional scutes on their shells. While some abnormalities can lead to premature death, others will not impact a hatchling’s likelihood to survive, such as the extra scutes for example. We are continuing our monitoring and hope to delve into identifying the causes at some point in the future.

References:

- Bárcenas‐Ibarra, A., de la Cueva, H., Rojas‐Lleonart, I., Abreu‐Grobois, F.A., Lozano‐Guzmán, R.I., Cuevas, E. and García‐Gasca, A., 2015. First approximation to congenital malformation rates in embryos and hatchlings of sea turtles. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 103(3), pp.203-224.

- Martín-del-Campo, R., Calderón-Campuzano, M.F., Rojas-Lleonart, I., Briseño-Dueñas, R. and García-Gasca, A., 2021. Congenital malformations in sea turtles: Puzzling interplay between genes and environment. Animals, 11(2), p.444.

- Köhnk, S., Brown, R. & Liddell, A. (2021): ‘Finding of a two-headed green turtle embryo during nest monitoring in Baa Atoll, Maldives‘. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 88(1), a1940, https://doi.org/10.4102/ojvr.v88i1.1940