Ghost gear is fishing gear that has been abandoned, lost or discarded (ALD), at sea, on beaches or in harbours, including nets, lines, traps, pots and fish aggregating devices (FADs).

Each year, ghost gear is responsible for trapping and killing a significant number of marine animals, such as sharks, rays, bony fish, sea turtles, dolphins, whales, crustaceans and sea birds. They can cause further destruction by smothering coral reefs, devastating shorelines, and damaging boats.

Below you will find answers to some of the most frequently asked questions we get about ghost gear.

Ghost Gear FAQ

Neither bycatch nor ghost fishing are intentional actions, rather they are by-products of fishing. The most important difference between bycatch and ghost fishing is that one involves active fishing gear, and one does not.

Both bycatch and ghost fishing can cause life threatening injuries, and sometimes death, of non-target marine species. But it is important to define these different causes of fishing-related mortality, as the two issues require slightly different management strategies.

Bycatch

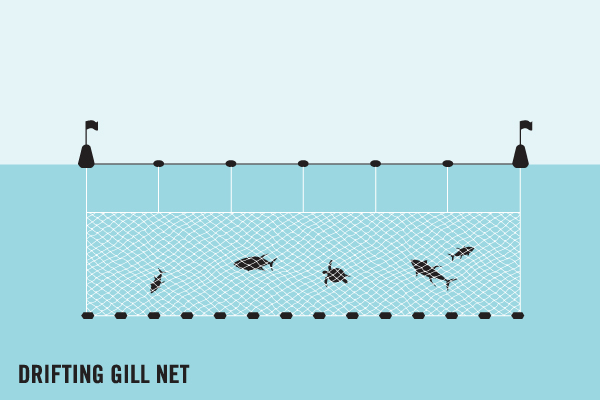

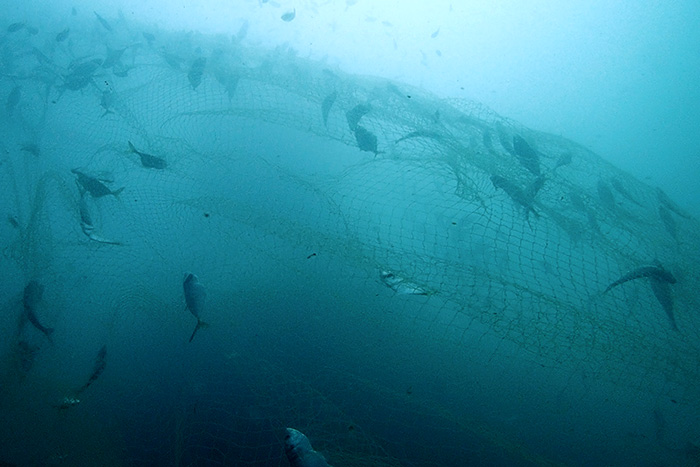

Bycatch is when fishing gear catches non-target animals whilst being controlled by the fishing industry. For example, purse seine fisheries often cast one large net around a school of fish (often tuna). Due to the size of the net, as well as catching the target species, it may also accidentally catch ‘non-target’ species, such as cetaceans, sharks and sea turtles.

Ghost Fishing

Ghost gear also catches and kills animals, but this happens despite the fishers no longer having operational control over the gear. For example, a fisher’s net may wash away or become dislodged during a storm. That lost net may then catch and kill marine life when drifting out in the open ocean, in a process called ghost fishing.

There are 4 key ways to tackle ghost gear:

- Reducing the amount of gear lost in the first instance

- Removing ghost gear from the ocean/beaches/harbours

- Recycling and repurposing of retrieved ghost gear

- Rescuing injured animals from ghost gear

When possible, all efforts should go into developing solutions that will prevent gear loss in the first instance.

Here are some specific examples of how different stakeholders can tackle ghost gear:

- Better transparency when reporting abandoned, lost or discarded fishing nets

- Better communication between fisheries to reduce conflict and subsequent gear loss

- Avoidance of superfine and easily breakable fishing nets

- Proper disposal of worn out fishing gear Making repairing nets common practice

- Taking responsibility for own gear e.g. gear marking so it can be traceable

- Actively reporting and removing gear when found

- Use of GPS topographic maps to reduce frequency of snagging incidents

- Better enforcement to reduce illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

- Be a part of a global effort. Ghost gear is a global issue so collaboration between governments is vital

- Banning or temporary closures of certain gear types, particularly in sensitive areas e.g. trawls, superfine gill nets, purse seine fisheries associated with drifting FADsHold responsible fisheries accountable

- Increase incentives for fishers to repair or recycle broken or worn out nets

- Increase incentives for fishers to bring back end of life fishing gear to port or beach side facilities

- Use of scientific research to inform decisions

- Use of more robust materials e.g. avoidance of superfine gill nets

- Implementing mitigation methods e.g. providing escape gaps in traps

- Implementing the use of biodegradable gear components into fishing gear design

- Continue to build baseline evidence e.g. where are the hotspots for ghost gear? How much ghost gear is there?

- Identify local/regional causes of gear loss e.g. through fisheries surveys

- Quantitatively assess the impact of ghost gear on marine life

- Reduce fish consumption if you are in the position to do so

- Make more conscious decisions when consuming fish e.g. actively avoiding fish caught by destructive fishing practices with high rates of gear loss

- Participate in clean ups e.g. beach cleans or ghost gear recovery whilst scuba diving

- Educate and spread awareness

Fishing gear becomes ghost gear when the fisher loses all operational control of the equipment. Gear loss can happen for various reasons, such as:

- Poor weather conditions

- Poor access to disposal or recycling facilities

- Lack of or inadequate gear maintenance

- High cost of retrieval

- Catch overload

- Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities

- Conflicts between fisheries

- Destructive fishing techniques.

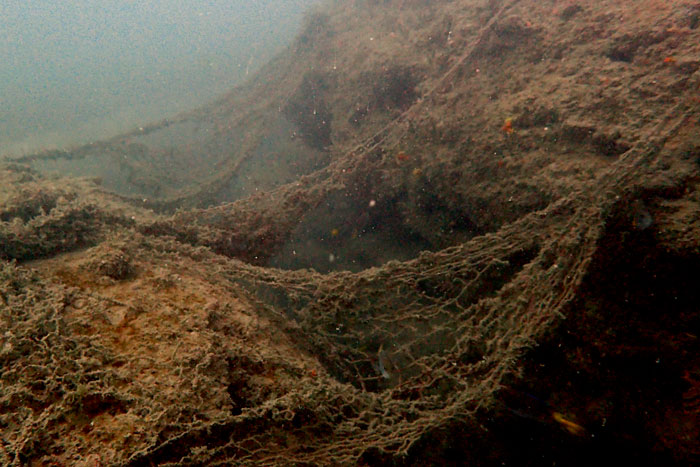

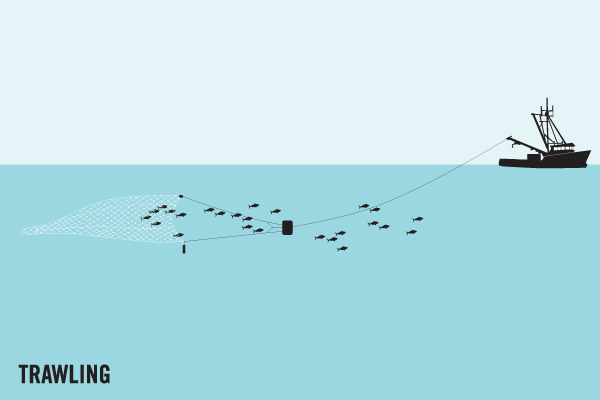

In Indian gillnet fisheries, for example, conflict between fisheries is the main cause of gear loss. Trawlers often drive straight through set gill nets, resulting in direct gear loss. This single net then has the capacity to smother an entire reef.

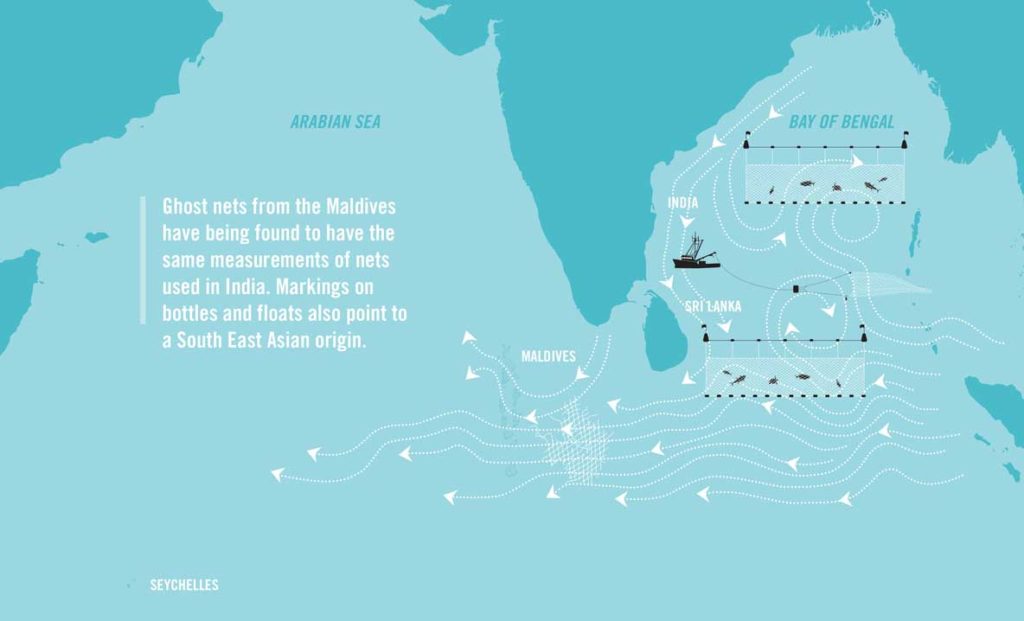

Another significant cause of gear loss is destructive fishing techniques. Bottom trawling, for example, involves dragging a huge net across the sea floor. During this method, fishing nets often snag on the bottom and break, leaving fragments of potentially entangling net behind. One example is in northern Australia, where trawl nets were the most abundant net type found stranded on beaches [4]. Similarly, trawl net fragments were one of the major gear types responsible for ghost gear found drifting into the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Maldives.

References

- Stelfox, M., Bulling, M. and Sweet, M., 2019. Untangling the origin of ghost gear within the Maldivian archipelago and its impact on olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) populations. Endangered Species Research, 40, pp.309-320.

- Thomas, S.N., Edwin, L., Chinnadurai, S., Harsha, K., Salagrama, V., Prakash, R., Prajith, K.K., Diei-Ouadi, Y., He, P. and Ward, A., 2020. Food and gear loss from selected gillnet and trammel net fisheries of India.

- Wilcox, C., Heathcote, G., Goldberg, J., Gunn, R., Peel, D. and Hardesty, B.D., 2015. Understanding the sources and effects of abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear on marine turtles in northern Australia. Conservation biology, 29(1), pp.198-206.

There is no simple answer to the question “how much ghost gear is in the ocean?”. In the 1970s it was estimated that 640,000 tonnes of ghost gear was produced each year, accounting for around 10% of ocean plastics. However, since ghost gear survey effort is often poor or sporadic, this is likely a gross under representation of the true amount of ghost gear in the ocean today. In Northern Australia alone, up to 3 tonnes of derelict nets have been reported per kilometre of coastline in a given year.

More research is needed to determine the current amount of ghost gear in our oceans today and to understand the effects that this is currently having on marine species at a population level. However, ghost gear is known to be cryptic and transboundary in nature. As a result, it can be extremely difficult to study.

References

- Gunn, R., Hardesty, B.D. and Butler, J., 2010. Tackling ‘ghost nets’: local solutions to a global issue in northern Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration, 11(2), pp.88-98.

- Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T. and Cappell, R., 2009. Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear.

- Wilcox, C., Hardesty, B.D., Sharples, R., Griffin, D.A., Lawson, T.J. and Gunn, R., 2013. Ghostnet impacts on globally threatened turtles, a spatial risk analysis for northern Australia. Conservation Letters, 6(4), pp.247-254.

Ghost nets are derelict fishing nets – fishing nets that have been abandoned, lost or discarded at sea. Sometimes this refers to one singular net. It may also refer to a conglomerate – a mix of various ghost gear and marine debris such as plastics.

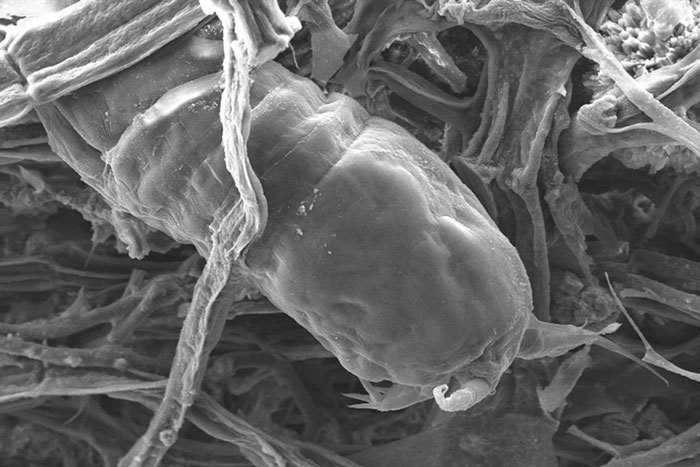

Fishing nets were historically made of natural or biodegradable materials, such as cotton, coconut and hemp. They are now predominantly made from more durable materials, such as synthetic plastics (e.g. high density polypropylene, high density polyethylene and nylon). Due to an increase in these synthetic materials, which can take hundreds of thousands of years to degrade, there has been a substantial rise in the amount of ghost gear accumulating in our oceans today.

There has been research into biodegradable fishing gear that degrades or decomposes after a certain amount of time in water, therefore reducing its capacity to ghost fish, but this has not yet been implemented on a large scale. Biodegradable gear, whilst not the solution to the problem of ghost gear, should be included in any responsible fishery to help combat the prevalence of ghost fishing.

References

- Kim, S., Kim, P., Lim, J., An, H. and Suuronen, P., 2016. Use of biodegradable driftnets to prevent ghost fishing: physical properties and fishing performance for yellow croaker. Animal conservation, 19(4), pp.309-319.

- Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T. and Cappell, R., 2009. Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear.

Ghost gear is fishing gear that has been abandoned, lost or discarded (ALDFG) at sea, in ports and at beaches. The term ‘ghost gear’ refers to all types of derelict fishing gear, whether that be nets, lines, traps and pots or fish aggregating devices (dFADs).

Ghost gear poses a grave threat to the marine environment, fishermen and local communities. Fishing gear is often targeted at one species or one group of species. However, when that gear becomes abandoned, lost or discarded, it does not discriminate. Whilst drifting with ocean currents, it will indeterminately catch and kill any marine life in its path. Consequently, ghost gear contributes to both the depletion of fish stocks around the world and the decline of many protected and endangered marine species.

Ghost gear take the form of a single net or line, or it may be a mixture of various materials. For example, some gear will drift with ocean currents and become entangled with other gear or marine debris, such as plastics, forming a conglomerate. These conglomerates can be particularly destructive due to their complex nature. Many marine species become entangled in these and, unfortunately, never make it out. In the Maldives, we often find olive ridley turtles with life-threatening injuries after being entangled in conglomerates of ghost gear, having likely been stuck there for months on end.

References

- Smolowitz, R.J., Corps, L.N. and Center, N.F., 1978. Lobster, Homarus americanus, trap design and ghost fishing. Marine Fisheries Review, 40(5-6), pp.2-8.

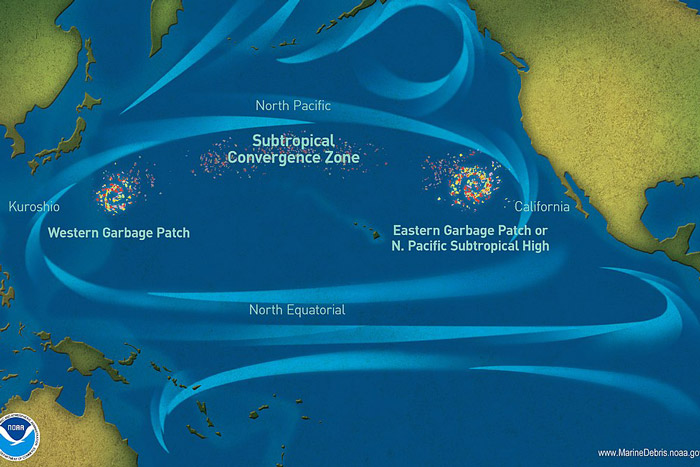

Ghost gear can occur in any environment where fishing takes place but is not restricted to these areas. Ocean currents can cause ghost gear to drift far from its origin. As such, it can be found in all marine habitats around the world from coral reefs hundreds of thousands of miles away from their point of origin, to the deep sea at over 3,000m below the surface.

Ghost gear can also accumulate in certain areas. Many plastics, for example, accumulate in oceanic gyres. A study of the famous ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’ demonstrated that ghost nets alone represent 46% of the 79,000 tonnes of plastic observed.

Moreover, some nations are particularly susceptible to the effects of ghost gear. For example, the geography of atolls and outer reefs in the Maldives (which draw a perpendicular line across the direction of ocean currents) often means that they act as traps for floating debris, thus compromising the sustainability of their local pole and line fishing techniques.

References

- Lebreton, L., Slat, B., Ferrari, F., Sainte-Rose, B., Aitken, J., Marthouse, R., Hajbane, S., Cunsolo, S., Schwarz, A., Levivier, A. and Noble, K., 2018. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Scientific reports, 8(1), pp.1-15.Vieira,

- R.P., Raposo, I.P., Sobral, P., Gonçalves, J.M., Bell, K.L. and Cunha, M.R., 2015. Lost fishing gear and litter at Gorringe Bank (NE Atlantic). Journal of sea research, 100, pp.91-98.

- Stelfox, M.R., 2021. The cryptic and transboundary nature of ghost gear in the Maldivian Archipelago. University of Derby (United Kingdom).

Wind and currents can cause ghost gear to drift far from its origin. Ghost gear can therefore end up in any type of marine habitat, including on beaches, coastal areas, harbours, coral reefs, and, of course, in both shallow and deep sea, causing an array of environmental and socio-economic issues:

Entanglement and entrapment of marine animals, often leading to severe injuries, including the amputation of limbs, and death.

Ghost fishing, a process in which abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear continues to catch and kill marine life.

Ingestion of fishing hooks, ghost nets and fishing lines by marine life and sea birds.

Smothering of coral reefs, damaging coral and even block access to necessary sunlight.

The dispersal of invasive species as microorganisms can accumulate on ghost gear overtime and ‘hitch-hike’ across ocean basins.

Devastation of shorelines and beaches, including sea turtle nesting beaches.

Ghost gear also poses a threat to boats and naval navigation, to divers, and to tourism by clogging up harbours and beaches around the world.

Ghost gear can be destructive regardless of its size or type. Even small fragments of broken gear can become a problem. Marine animals can ingest small pieces of ghost gear, whilst seabirds can incorporate fragments into their nests, posing risks of entanglement and ingestion to both breeding adults and their young. Indirectly, ghost gear also impacts livelihoods and fishing communities through the process of ghost fishing.

References

- O’Hanlon, N.J., Bond, A.L., Lavers, J.L., Masden, E.A. and James, N.A., 2019. Monitoring nest incorporation of anthropogenic debris by Northern Gannets across their range. Environmental Pollution, 255, p.113152.

Ghost gear is known to be cryptic and transboundary in nature. In simple terms, this means it can be difficult to see or find and may drift long distances, often crossing political and maritime borders along the way.

Ghost gear inevitably succumbs to the forces of nature, such as wind and ocean currents. These forces drive ghost gear far beyond our reach, passing through multiple habitats along the way. Our efforts to measure the impact of ghost gear is further complicated by its ability to ghost fish. Ghost fishing eventually results in nets sinking due to its increased weight, ultimately ‘disappearing’ from our field of vision. Often it is not what you can see that is the concern but what you cannot!

Finally, ghost gear is often unmarked and forms conglomerates of many gear types mixed together by ocean currents and winds. Therefore when found it is hard to know how long it has been drifting and where it has come from.

Though it is hard to study ghost gear, we do know for sure that we can no longer assume that the countries with high levels of ghost gear are contributing the most to the problem. Equally, we cannot assume that countries with low levels of observed ghost gear are of no concern.

‘Ghost gear’ probably got its name because of its cryptic nature and devastating effects. It can be can hard to see due to the gear itself – many fisheries opt for superfine, almost invisible, nets to increase their catch. It can be hard to find when it sinks into the deep sea and beyond our reach.

In addition, ghost gear, even though no one has control of it, continues to catch fish and other marine life. It is almost like it is being operated by a ghost crew of wind and currents.