A monster ghost net surfaces in Laamu Atoll

In late December, an intern with the Maldives Underwater Initiative (MUI), noticed something unusual while guiding guests on a snorkelling trip to Aneel Faru reef in Laamu Atoll. Wrapped around a coral pinnacle three metres below the surface was a large, multi-coloured fishing net.

Made of several types of rope and heavily colonised by algae and small marine organisms, the net had clearly been drifting in the water for a long time before becoming entangled on the reef.

What is ghost gear? Abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), commonly known as ghost net or ghost gear, drift freely in oceanic currents, trapping and injuring marine life in their path, including sea turtles.

ORP’s Laamu Sea Turtle Biologist Juliette, intern Nishad, and members of MUI, quickly mobilised to remove the net. Once on site, they split into an underwater dive team and a surface support team. Divers carefully cut the net into smaller sections to avoid damaging the coral, passing each piece to the surface team to check for trapped animals. Fortunately, none were found.

A tough start in life: Kuda’s story

Just days after the Laamu recovery, a post-hatchling olive ridley had a tough start in life when she became entangled in a ghost net.

The tiny turtle, later named Kuda (meaning small in Dhivehi) was rescued by gardeners working on the beach at One&Only Reethi Rah in North Malé Atoll. Despite her small size, Kuda had ligature wounds on her right front flipper and both hind flippers, as well as predator wounds on her carapace (shell). She is now receiving expert medical care from ORP’s veterinary team, and we are optimistic for her recovery.

Kuda is not an isolated case. Entanglement injuries are the leading cause of admission to ORP’s sea turtle clinical facilities in the Maldives, accounting for almost 61% of all cases since the Marine Turtle Rescue Centre opened in 2017.

The North-East monsoon: entanglement season

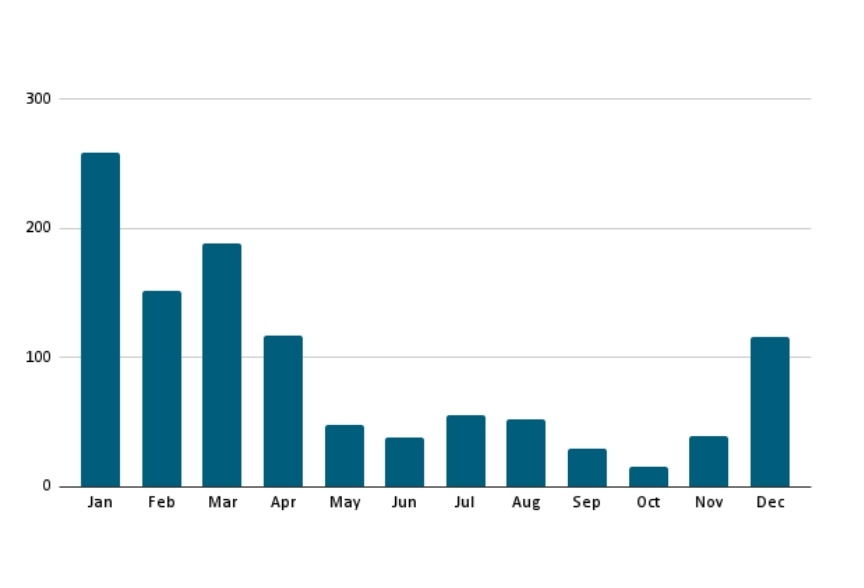

Although entanglement incidents occur year-round, November to March is peak season in the Maldives. Known locally as Iruvai, the North-East monsoon brings strong currents flowing from the Bay of Bengal towards the Maldives, carrying floating debris, including ghost nets, and, at times, sea turtles already trapped within them.

Once entangled in ghost gear, sea turtles may drift for days or even weeks, sustaining severe injuries, dehydration and exhaustion. Many arrive at rescue facilities in critical condition, with deep lacerations, infections, or to partial or complete flipper amputations. In some cases, amputated flippers show signs of healing, indicating that the turtles have survived prolonged entanglement before reaching shore or being rescued.

Because these cases peak sharply in the Maldives during the North-East monsoon, we refer to this period as entanglement season.

Why are most entangled sea turtles in the Maldives olive ridleys?

One question keeps surfacing: why are so many of the sea turtles we rescue in the Maldives olive ridleys? They are rarely seen near shore, yet they dominate our rescue records.

Research led by ORP’s CEO & Founder, Dr Martin Stelfox, found that olive ridleys account for 94% of recorded sea turtle entanglements in the Maldives. Since 2017, they have also made up around 80% of admissions to ORP’s clinical facilities.

The story starts far from the Maldives, in the North-Eastern Indian Ocean – a region with many olive ridley foraging sites, that also overlaps with heavy fishing effort. This means more ghost gear ends up at sea, increasing the chance of entanglement for olive ridleys.

As the North-East monsoon blows toward the Maldives, seasonal currents transport drifting ghost nets and olive ridleys, some already entangled, into the Maldivian waters. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of olive ridleys also undertake their annual migrations to nesting sites in India and Sri Lanka between November to March for synchronised nesting. This incredible spectacle is known as an arribada.

With migration, foraging sites, peak fishing, and monsoon drift all occurring together, the risk of olive ridleys encountering ghost gear rises even further.

Certain aspects of olive ridley behaviour can further increase their vulnerability. They spend much of their lives in the open ocean, are known to investigate floating debris, and often bask at the surface – traits that make encounters with drifting ghost gear more likely.

How do we know that olive ridleys come from India and Sri Lanka?

Dr Stelfox’s genetic research confirmed that most entangled olive ridleys in the Maldives originate from nesting populations in Sri Lanka and eastern India. His findings also suggest these sea turtles may actively use Maldivian waters as feeding grounds – a conclusion supported by occasional sightings of free-swimming olive ridleys, and cases of sea turtles rescued shortly after becoming entangled.

Ghost gear: A problem without borders

Most ghost gear found in the Maldives does not originate in the country. Commercial fishing is banned and Maldivian fisheries rely on a traditional pole-and-line method, perfected over 800 years, which uses no nets.

Dr. Stelfox’s research suggests that most ghost gear found in Maldivian waters come from fisheries operating in neighbouring regions or international waters, including international and local large-scale purse seine and gillnet fisheries in the Bay of Bengal and beyond. Carried by powerful ocean currents, lost fishing gear can travel thousands of kilometres before reaching the Maldives, highlighting the transboundary nature of the ghost gear problem.

Some drift patterns also suggest illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing activity within the Maldives’ exclusive economic zone.

What can be done?

Ghost gear is a global issue and an unfortunate byproduct of modern fishing. It occurs when fishing equipment is lost or abandoned due to heavy catch, bad weather, poor net maintenance, or improper disposal. Once lost, nets can drift for months or even years, travelling far beyond their point of origin.

While the ghost gear problem can feel overwhelming, it is not unsolvable. Meaningful action can happen at several levels:

- Stronger policies and accountability: Clearer regulations around gear loss, improved reporting and disposal systems, and stronger enforcement can help reduce net abandonment in the first place. Prevention is key.

- Ghost gear removal and clean-ups: Removing existing ghost gear saves lives immediately. Reporting sightings and organised clean-ups from reefs and beaches can help tackle the problem.

Since 2013, ORP has removed more than 15 metric tons of ghost gear in the Indian Ocean region. The Laamu ghost net alone weighed in at 34.6kg. In Pakistan, where we run a circular economy project repurposing ghost gear to pet leashes, we recovered a further 205 kg in the last three months. - Rescue and conservation medicine: Even with preventive measures in place, some sea turtles will inevitably become entangled. This is where rescue networks, trained responders, and clinical facilities can play a vital role. Timely rescues and specialised veterinary care can mean the difference between life and death, for post-hatchlings like Kuda, and for adults like Karaa.

Entanglement season may return every year, but so does the opportunity to act by removing ghost gear, rescuing injured turtles, and working together to protect the ocean we all share.