Satellite tagging is a key tool for conservation of wild animals, including sea turtles. It enables us to understand many things about sea turtles – like their migration, diving behaviour, their favourite foraging grounds, what water temperature they prefer, and potential interactions with human activities. We can collect robust scientific evidence for where we should define marine protected areas, facilitate establishment of multinational agreements for conservation, and provide recommendations for fishers to minimise bycatch.

What is satellite telemetry?

Satellite telemetry is a process of determining the location of an animal on the earth using satellite tags. A satellite tag is a device which tracks the location of a tagged animal by sending location information to a system of satellites (usually in the form of longitude and latitude data). The satellites then transmit the location back to receivers on the Earth’s surface. When tracking aquatic animals such as sea turtles, this process happens whenever they are at the surface. Water absorbs the satellite signal, preventing direct contact with the tracking device while it is submerged. By placing a satellite tag on a wild animal, scientists can view the animal’s location in real time – kind of like the GPS we have in our phones! This GPS data can go a long way to inform conservation efforts.

Information received from satellite tags

Not only can we see where the sea turtle is swimming in real time. We can also get additional information by adding different sensors on the tag. For our research projects, we use Telonics satellite tags with location, depth, and temperature gauges. This information allows us to understand and more accurately locate the sea turtle’s favourite foraging grounds and migration corridors. Diving profiles returned from satellite tags can also give us information on where deep foraging dives are occurring, which can help us accurately model where foraging areas are.

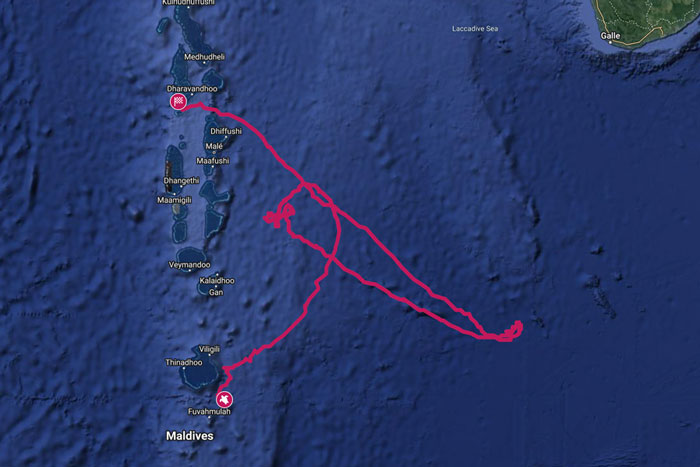

Until very recently, female sea turtles were the focus of sea turtle research as they can be regularly encountered when nesting; this makes them easily accessible to scientists. However, what if male sea turtles do not have the same migratory corridors and diving patterns as females? From what we know from our Rescue Centre, adult male sea turtles are rarely found entangled. Therefore, satellite tracking of their movement patterns may help shed light on how they manage to avoid entanglements. Satellite telemetry could also help identify hot-spots of ghost net encounters, leading to targeted strategies for conservation. Satellite tags can be placed on both females and males on any life stage. This opens many doors for research to collect important information on these elusive marine animals.

How information from satellite tags is used in conservation

Marine animals are difficult to study due to their elusive behaviours, extensive range of movement, and difficulty in accessing them in the open ocean. Therefore, satellite telemetry is a great tool to better understand sea turtle biology and ecology. Analysis of the data can give us crucial information to:

- Support the need of conservation and management of Marine Protected Areas

- Facilitate the establishment of multinational agreements for their conservation by showing that marine wildlife does not see international maritime boundaries as humans do

- Help tackle anthropogenic threats such as bycatch and vessel strikes by pinpointing turtle hotspots, and

- Understanding post-release rehabilitation success.

As our scientists receive more and more locational data, the more robust our recommendations can be; as long as the satellite tag remains on the sea turtle and is not covered by biofouling organisms such as algae or barnacles, more data can be obtained.

What happens to used satellite tags?

Satellite tags will naturally detach from the sea turtle’s carapace after 6 months to a year as sea turtles shed their scutes. However, sea turtles scratch their carapace in order to remove epibionts such as barnacles to stay clean. This means that satellite tags could also be detached before their batteries run out.

Even though tags may be recovered by researchers or fishers, unfortunately, they mostly end up as marine litter. By the time a tag detaches, the turtle could have swam hundreds – or even thousands – of miles away from where it was released and the battery will either have run out or the tag will be fully submerged with the sea blocking the satellite signal. The logistics of collecting a tag would therefore be unreasonable as it is impossible to track it for collection.

However, the loss of a single tag in the background of the data obtained is inconsequential. As mentioned before, the data collected can be used to discover information such as important foraging grounds, ghost net encounter hotspots, or migratory corridors that were not previously known. All this information can be used to develop protected areas, whether within national waters or in the high seas. So, even though the tags may end up becoming marine litter once they detach, the information collected from them will benefit the species, making this loss completely worth it.

Throughout our research projects, we carefully consider how many tracking devices are needed to provide the information needed to perform meaningful analysis to keep the amount of tags brought into the ocean to a minimum. New advances in satellite tagging technology can also make these short periods of data collection be worthwhile as more information can be obtained or if satellite tags can be designed to stay on for longer.

Advances in sea turtle tracking

Sea turtle tracking devices have evolved significantly since the first research study conducted in 1979. This began when four sea turtles were fitted with a harness attached to a rope; the rope was then tied to a buoy which was equipped with a transmitter. The transmitter sent the turtle’s location for a maximum of 34 days.

Nowadays, the satellite tracking devices are typically small, relatively light, and attached directly onto the carapace with well established gluing methods. This does not hurt the turtle, does not damage the integrity of the shell or impact the swimming capability of the animal as tracking devices are chosen to fit the animal. The battery life can last for over a year, and not only can we see the position of the sea turtle, but modern tags also include different sensors depending on what one wants to study. In addition, the Telonics tags used by ORP have internal antennas rather than an external whip antenna. This is a significant advancement as external whip antennas were subject to breaking and are a point of weakness in many tags.

As technology advances, so do satellite tags, making them more ergonomic and lighter. In addition, ORP is co-developing the SnapperGPS tags with the Arribada Initiative. These are new low-cost telemetry tags to scale up the monitoring of rehabilitated and wild sea turtles globally. They are designed to collect fine scale movements to understand foraging behaviours and nesting attempts of nesting sea turtles.

Bibliography

- Abalo-Morla S, Belda EJ, March D, Revuelta O, Cardona L, Giralt S, Crespo-Picazo JL, Hochscheid S, Marco A, Merchán M, Sagarminaga R, 2022. Assessing the use of marine protected areas by loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) tracked from the western Mediterranean. Global Ecology and Conservation 38:e02196.

- Blumenthal JM, Solomon JL, Bell CD, Austin TJ, Ebanks-Petrie G, Coyne MS, Broderick AC, Godley BJ, 2006. Satellite tracking highlights the need for international cooperation in marine turtle management. Endangered Species Research.2:51-61.

- Hamilton RJ, Desbiens A, Pita J, Brown CJ, Vuto S, Atu W, James R, Waldie P, Limpus C, 2021. Satellite tracking improves conservation outcomes for nesting hawksbill turtles in Solomon Islands. Biological Conservation. 261:109240.

- Hays GC, Hawkes LA, 2018. Satellite tracking sea turtles: Opportunities and challenges to address key questions. Frontiers in Marine Science. 5:432.

- Mansfield KL, Wyneken J, Porter WP, Luo J, 2014. First satellite tracks of neonate sea turtles redefine the ‘lost years’ oceanic niche. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281(1781):20133039.

- Robinson DP, Hyland K, Beukes G, Vettan A, Mabadikate A, Jabado RW, Rohner CA, Pierce SJ, Baverstock W, 2021. Satellite tracking of rehabilitated sea turtles suggests a high rate of short-term survival following release. Plos one;16(2):e0246241.

- Stoneburner DL, 1982. Satellite telemetry of loggerhead sea turtle movement in the Georgia Bight. Copeia. 28:400-8.