Think about an adorable turtle hatchling, incredibly tiny as it crawls out into the world! It is easy to focus on the beauty and magic of these little babies and forget to look deeper at what might be left behind in the nest.

But the truth is, lots of eggs never hatch and many baby turtles don’t even get to take their first breath.

There are over 350 species of turtles – this includes land turtles (tortoises), sea turtles, and freshwater turtles (terrapins); collectively, they all belong to the order Testudines.

Many turtle species play critical roles in maintaining healthy environments that other animals and plants depend on. Without these important reptiles, entire ecosystems can collapse. In some places, this is already an unfortunate reality due to recent extinctions.

For example, in Mauritius, the extinction of the Mauritian tortoises also meant that their important role in grazing and seed dispersal disappeared with them. To help fix this, conservationists introduced other tortoise species, like the Aldabra giant tortoise, which helped restore some balance in the ecosystem. This shows how important it is to protect surviving turtle species, as they not only keep ecosystems running but can also help restore damaged ones.

The extinction crisis

Even though turtles are crucial for healthy ecosystems, they are facing an extinction crisis. Over half of all turtle species are threatened, and about 20% are critically endangered. Among sea turtles, 6 out of 7 species are at risk, with some populations declining by more than 90% in recent decades, like the Pacific leatherback.

One key step to help turtles survive is to ensure they are reproducing successfully. Unfortunately, hatching failure – when an egg does not hatch – can be a big problem for turtle populations.

Why do turtle eggs fail to hatch?

- The egg was not fertilised (i.e., sperm did not fuse with the egg cell), also known as fertilisation failure, or

- It was fertilised, but the resulting embryo died, known as embryo death

When you look at an unhatched egg, the question is: Did it never have life at all, or did life stop developing at some point? Eggs fail to hatch for one of two reasons:

It’s important to know which one happened, because each has a different cause, with different possible solutions.

Why does this distinction matter?

If the embryos are dying in the egg, it may mean something in the environment, like temperature, pollution, or disease, is harming them.

However, if eggs aren’t fertilised to begin with, that may point to problems with adult turtles – maybe they’re not finding mates, something is wrong with the male’s sperm, or the individual turtle has health problems affecting their ability to reproduce. Therefore, by figuring out whether unhatched eggs were fertilised to begin with, scientists can target conservation efforts more effectively.

Even though it’s really important to know if an unhatched egg was ever fertilised, most studies on turtle hatching failure hadn’t really checked this properly. The few that did often used methods that weren’t very reliable.

Sometimes it’s easy to tell – if there’s a visible embryo inside the egg (image right), you know it was fertilised. But many unhatched eggs look completely empty, with just a regular yolk (image left). But that doesn’t always mean these eggs were never fertilised.

In the past, scientists often relied on cutting open eggs (simple dissections) and looking inside (visual checks). The problem is, this method cannot show whether fertilisation happened at the microscopic level. That meant a lot of the ‘empty-looking’ eggs remained a mystery – were they truly unfertilised, or did the embryo die very early on?

Because of this uncertainty, our understanding of why turtle eggs fail to hatch was limited. It became clear that we needed better tools to solve this puzzle.

A new approach to detecting fertility

This is where my study comes in. My supervisor, Dr Nicola Hemmings, is one of the brilliant minds to have helped create a special microscope-based method to check if bird eggs were fertilised.

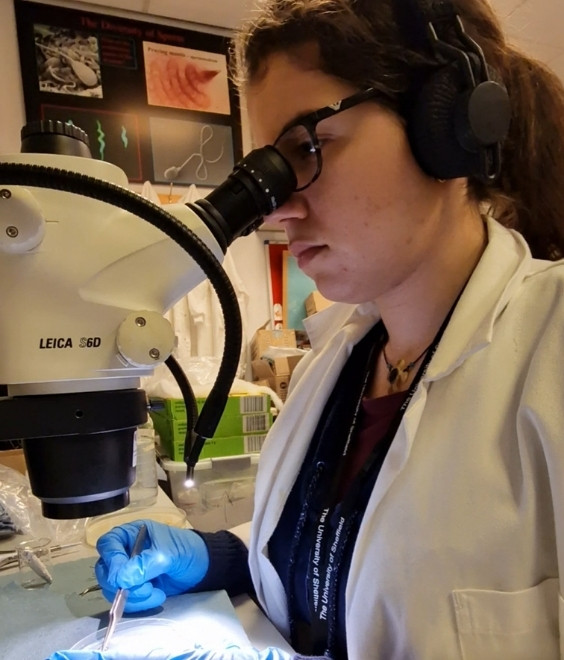

I pitched the idea of readapting her methods to turtles and this has completely shaped my work since (image left).

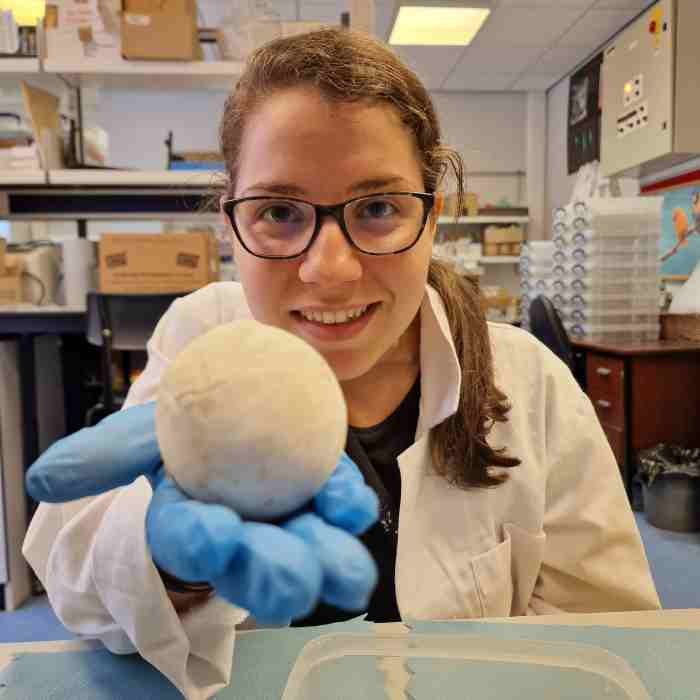

Working with two UK zoos and eight conservation groups in the Seychelles, including ORP Seychelles, we tested our adapted method on more than 150 undeveloped eggs from five different turtle and tortoise species, including critically endangered hawksbills and endangered green turtles.

Seeing the unseen: What do fertilised sea turtle eggs at the microscopic scale look like?

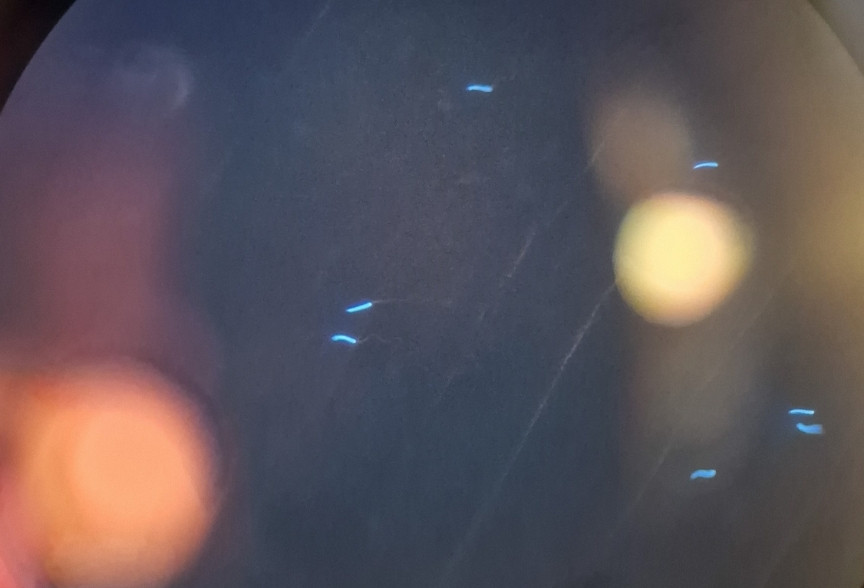

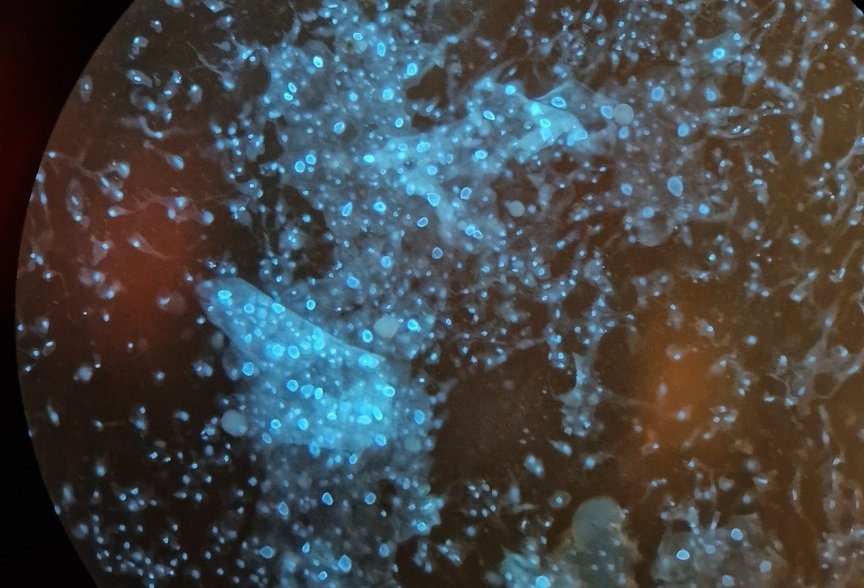

From undeveloped sea turtle eggs, we collected specific parts of the yolk where fertilisation happens. We stained these samples with a special dye (called Hoechst 33342), which can reveal the invisible presence of any baby turtle cells, as well as sperm cells.

The dye makes these tiny cells glow a bright blue under a fluorescence microscope – almost appearing like a glowing constellation of stars in the night sky.

By looking at the eggs this way, we can tell if they were ever fertilised, even if no baby turtle is visible. This helps solve the mystery of why so many eggs don’t hatch.

What we found

We successfully examined 79% of the turtle eggs we received, and determined whether they were fertilised or not. We classified the eggs as follows:

- Fertilised if embryonic cells were visible

- Unfertilised if no embryonic cells and very few or no sperm were found

- Inconclusive if they were too degraded to be certain

We found that:

- Most of the eggs (75%) had been fertilised but suffered early embryo death.

- Even higher rates of early embryo death were found in hawksbill and green turtles than in other turtle species

This shows that embryo death is the main cause of hatching failure, not lack of fertilisation in turtle eggs in Seychelles.

However, one species – the Aldabra giant tortoise – showed slightly higher rates of fertilisation failure, indicating that fertility may be more of a concern. More research is needed to fully understand this potential trend across the different Aldabra giant tortoise subpopulations.

Embryo death in sea turtles

In both hawksbill and green turtle samples, most of the eggs were fertilised. In fact, we found only one unfertilised egg – a very unusual hawksbill egg with three yolks. It came from a problem nest where most of the eggs had failed to hatch, many were oddly sized, and the few hatchlings that did emerge were very small and showed signs of dwarfism.

Since almost all the eggs were fertilised, it seems that mating or reproductive behaviour is not a big problem for hawksbill or green turtles in Seychelles. Instead, our results show that most eggs fail to hatch because the embryos didn’t survive.

Why these findings matter for conservation

This new method of checking fertility in eggs is both informative and minimally invasive. It is carried out after the normal hatching period, so healthy eggs are not disturbed. Even eggs that have been in the nest for months can still provide microscopic evidence. This is important because scientists once thought such degraded eggs couldn’t be studied at all.

The data we’ve gathered on fertilisation and embryo survival helps conservation teams know which problem to focus on. For example, since as per the study, embryo death was the main reason sea turtle eggs didn’t hatch, conservation efforts could focus on improving nest conditions and reducing harmful environmental factors.

On the other hand, if research continues to show that Aldabra giant tortoises have higher levels of fertilisation failure, the focus should shift to making sure females are able to mate successfully with healthy males.

Looking ahead

Our fertility test is very powerful, but it needs special lab equipment. One day, we hope to be able to do this kind of test right out in the field.

These findings are just the beginning, helping us understand how things like nest temperature, disease, and pollution affect turtle reproduction. In the future, we hope captive breeding, reintroduction projects, and nest monitoring can all use these tests to learn why some eggs don’t hatch.

To support this, we’ll soon be sharing our step-by-step guide in the Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles (by the IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group), so conservationists around the world can use it.

Now that we can detect early hatching failure, the next step is to turn this knowledge into action and build conservation strategies around it. Because every hatchling that reaches the sea is a victory for science, conservation, and hope.

(Images of microscopic cells, Aldabra giant tortoise, and three yolked egg have been reproduced with permission from Alessia Lavigne)

References:

- Lavigne, A. & Bullock, R. & Shah, N. & Tagg, C. & Zora, Anna & Hemmings, N.. (2024). Understanding early reproductive failure in turtles and tortoises. Animal Conservation.

- Griffiths, C. J., Hansen, D. M., Jones, C. G., Zuël, N. & Harris, S. (2011). Resurrecting Extinct Interactions with Extant Substitutes. Current Biology, 21(9), 762–765.

- Griffiths, C. J., Jones, C. G., Hansen, D. M., Puttoo, M., Tatayah, R. V., Müller, C. B. & Harris, S. (2010). The Use of Extant Non-Indigenous Tortoises as a Restoration Tool to Replace Extinct Ecosystem Engineers. Restoration Ecology, 18(1), 1–7.

- Stark, G. & Galetti, M. (2024). Rewilding in Cold Blood: Restoring Functionality in Degraded Ecosystems Using Herbivorous Reptiles. Global Ecology and Conservation, 50, e02834.

About the author:

Alessia Lavigne is an Italian/Seychellois PhD candidate at the University of Sheffield whose work focuses on uncovering the causes of reproductive failure in threatened turtles and tortoises. Combining microscopy-based techniques adapted from avian science, with field studies, her research aims to sharpen conservation strategies for the effective protection of testudines.