We’re excited to share the very first issue of – Turtle Tidings from Kenya, our quarterly newsletter, bringing you closer to the heart of sea turtle conservation along Kenya’s coast. Thank you for being part of this journey, together, we’re helping secure a brighter future for sea turtles and the oceans our world depends on. Not subscribed yet? Join us here!

Could a sea turtle be our guiding star?

Throughout history, our sea-faring ancestors have looked up to the skies, singling out the brightest stars to navigate unchartered waters. Today, our team and divers in Kenya keep that tradition alive. Using the adage ‘as above, so below’, they navigate the depths of the ocean, guided by their favourite star.

Only, this one in particular has a brownish-green domed body, four flippers, and a softly curious gaze. Meet Bob, the much-adored green sea turtle of Galu. First spotted in July 2018, Bob has become such a fixture that divers now use her presence to find their way around the dive site.

“She’s often the first turtle on the reef to be visited by our team and the dive centre staff. Everyone knows Bob, she’s a local star.” says Diana, ORP Kenya’s Sea Turtle Biologist.

But Bob’s a ‘she’? Yep, sea turtles are kicking gender stereotypes to the curb, albeit unknowingly. When Bob was spotted as a small juvenile, her carapace measured not more than 45 cm. At the time, there was no way to know her sex through visual cues. Sea turtles mature slowly and the only reliable sign is tail length: a long tail signals a male, a short one a female. Bob’s adopter took a shot in the dark and chose a traditionally male name.

The years went by, and Bob grew, but her tail didn’t. It became clear that Bob was in fact a female. While we fondly watched her grow, Bob remained faithful to Galu, giving us multiple sightings every year. Her behaviour matches scientific observations of green sea turtles showing strong site-fidelity in coastal Kenya.

However, fluctuations can occur, during nesting migrations or through habitat disturbances, such as the coral bleaching event of 2024.

Coral bleaching occurs when ocean temperatures rise, causing corals to expel algae living in their tissues and turn white. If heat stress continues, corals can even die, leading to ecosystem collapse. Since reefs are important feeding and resting grounds for juvenile sea turtles, their survival is directly tied to the health of reefs.

Yet, even against the pale backdrop of bleached reefs, Bob stayed. We photographed her moving through the white corals, a striking reminder of both fragility and resilience. Her presence underlined why localised research and conservation is essential – sea turtles like Bob depend on marine ecosystems, even in their most vulnerable state.

Today, the bleached reefs of Galu are slowly recovering, and Bob is still here – our steadfast North star in Southern waters. Unbeknownst to her, she has become a symbol of hope, guiding us through the heavy waters of conservation.

What it means to be a woman at the heart of change

“People criticised me and would often ask why I ‘left my husband’ to go around and talk about sea turtles,” says Fatuma Kirinzo, a strong-willed Balozi wa Kasa (Sea Turtle Ambassador) from Chale-Jeza.

Fatuma grew up in a traditional fishing family where sea turtles were seen only as food. Like many in her community, she too believed they were just another resource.

“When some groups started insisting that sea turtles must not be consumed, I wondered what was so special about these animals,” she recalls.

Curiosity drove her to our Sea Turtle Ambassador (STA) Programme, co-developed in 2023 with fishing communities to encourage conservation leaders at the grassroots. Fatuma is one of our 129 local ambassadors to have received training in sea turtle ecology, threats, emergency protocol such as disentanglement from fishing nets, and bycatch reporting.

For Fatuma, the STA programme shifted her perspective entirely. Learning how sea turtles maintain healthy oceans and fish stocks gave her a new appreciation for the species. Soon, alongside her roles as wife, mother, and basket weaver, she embraced another identity – that of a conservation leader.

As part of the programme, we equipped Fatuma and other STAs with outreach materials and encouraged them to lead conservation conversations within their communities. Built on peer-to-peer learning, the programme ensures leaders share knowledge in ways that are relatable and personal, thereby making change more accessible. Between January and June 2025 alone, our Ambassadors reached over 5,000 people in their communities!

But Fatuma’s journey has not been easy. “Initially, a lot of people thought I was being paid to do this, and therefore demanded payment to attend my awareness sessions” she says.

The ocean is often viewed as a male space, and for a woman to speak with authority about it came with resistance. “Men, in particular, were harder to convince than women and children. People would resist the message, especially about not consuming sea turtles, but with regular sessions they seem to have softened” Fatuma explains, stressing that patience is key.

Interacting with other women STAs has helped Fatuma pick up interesting strategies – such as using the influence of husbands or fathers (who are respected fishers) to strengthen the message of conservation.

In Chale-Jeza villages, local attitudes towards sea turtles are now shifting. People are starting to report bycatch and mortalities to the STAs, showing a new sense of responsibility. Curiosity is also growing, as Fatuma shared with pride how one woman recently asked for a booklet so she could teach her children at home.

“Women have a central role” says Fatuma emphatically. “They influence their families and can discourage their husbands and children from consuming turtles. As each home changes, we can show what a big part we can play within societies” she says.

Fatuma herself has transformed too. While her role was once dismissed, she is now seen as a respected leader, especially as more Ambassadors join the movement.

Her advice to other young women who want to join as Ambassadors is powerful in its simplicity: “Do not fear conservation work. It is an inspiring opportunity to protect the environment while also helping your community.”

Through leaders like Fatuma, our programme has quietly weaved itself into the daily life of the communities, driving positive change slowly but surely.

Hidden in the sand: What 13 beach clean-ups revealed about plastic pollution in Diani

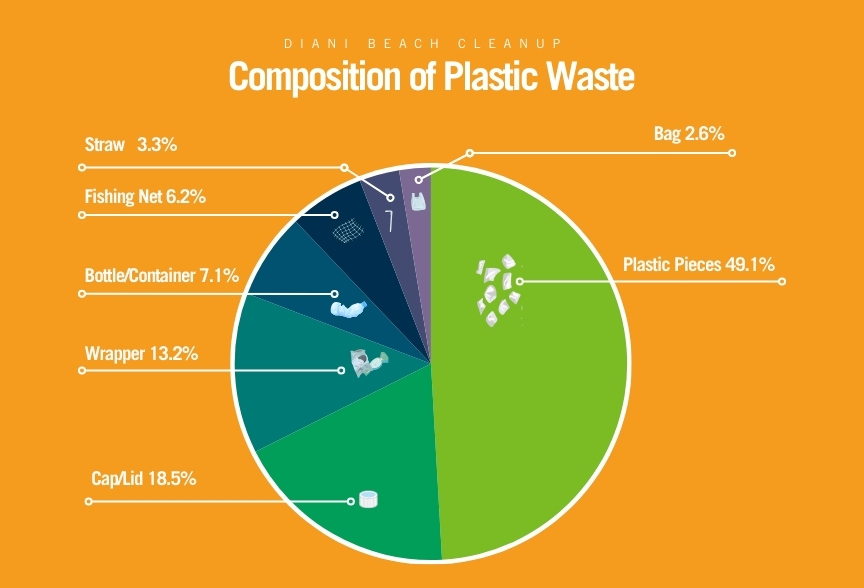

When we think of plastic pollution, the most common image our mind conjures is plastic bags and straws. However, our recent workshops on sea turtle nesting habitats with 294 Camp Kenya students revealed something more interesting.

We kept things simple, limiting our study to a 1 km stretch of Diani beach. Over 3.5 weeks, our team guided students in 13 half-hour cleanups to understand the local scale of plastic pollution on sea turtle habitats.

The students also sieved the trash to look for small plastic pieces (2cm or less). They recorded 9,397 small pieces of plastic, 83% of which were found at the top of the beach – the zone where sea turtles usually dig their nests. The most common size was 0.5 – 1 cm, just small enough to often go unnoticed by the naked eye.

During the workshops, we also discussed what happens to plastics that enter the ocean, and how long they take to break down. For example, most bottle caps are made from polypropylene (PP) or high-density polyethylene (HDPE). PP can take 20–30 years to decompose, while HDPE may take over 100 years. Under less favourable conditions, such as deep landfill or ocean environments with little sunlight and oxygen, the process may stretch up to 500 years. And like most plastics, bottle caps may never fully biodegrade, instead breaking down into microplastics that persist for centuries.

This activity proved to be an eye-opener for everyone. The students observed first-hand how something as ordinary as a bottle cap or wrapper can persist in nature and harm wildlife. It also gave them space to reflect on their own choices, and how small changes can help our environment.

We are deeply grateful to Camp Kenya for making these interactions possible. Every educational session we conduct is an exchange – we share our work and values, and in return, the students’ curiosity and insights remind us that there’s no end to learning.

From intern to biologist: Diana’s journey in sea turtle conservation

Most people will tell you they love sea turtles. Sage-like reptiles gliding gracefully across the ocean, what’s not to love?

But when Diana Kerubo Nyakundi, ORP Kenya’s Sea Turtle Biologist, says she loves sea turtles, it’s clear there’s more.

Yes, she’s smitten by them, but what Diana truly loves is the adventure and discovery that comes with working alongside these reptiles.

Diana was bitten by the adventure bug young. Though she grew up in Masai Mara, it wasn’t lions or elephants that kept her entertained.

“I loved swimming in the river, since there was no ocean,” she recalls. “I was a naughty child and one day I almost drowned. My parents thought I would never return to water,” she chuckles. But Diana’s spirit took her right back to the river.

“Growing up, I didn’t really have anyone to look up to, but I loved reading and learning about new things, which is what drives my interest in research today,” says Diana.

While Masai Mara inspires many to work in the savannahs, Diana’s need for adventure carried her to the sea. After completing her Bachelor’s in Marine Resource Management, she set out to look for opportunities in the field.

“I had been following ORP on social media and loved the research the team was doing, so I decided to write to them,” says Diana. Charmed by her cheery personality and genuine interest, the ORP Kenya team welcomed Diana as a Sea Turtle Monitoring Intern.

“With ORP I got the opportunity to not just dive, but also to learn and practice in-water monitoring and research,” says Diana, now a certified PADI Rescue Diver with over 500 dives. Her strong performance earned her a full-time position as a sea turtle monitoring assistant, and just a year later she became the sea turtle biologist for ORP Kenya.

Diana’s most memorable moment came on her birthday in 2023. “The sea turtles gave me the best birthday present. I was out on a dive when I spotted Maya, a female hawksbill – and also the first turtle I ever sighted – interacting with Aniel, a juvenile green turtle. It seemed like a friendly interaction, with Aniel gently nipping Maya,” she says excitedly.

Sea turtles are believed to be largely solitary animals, coming together mainly to mate or nest. But greater in-water monitoring is revealing more evidence of social interactions. Still, cross-species encounters like Maya and Aniel’s remain rare.

Diana continues to spot green and hawksbill turtles together – sometimes even competing for a coveted resting spot on the reef. Remarkably, she can identify over 30 individual turtles in just a glance.

“I am very excited for the future. We’re hoping to explore more dive sites in Kenya, and I cannot wait to add more turtles to our database and learn about their behaviour,” she says. Diana also hopes to see more Kenyans diving and participating in sea turtle conservation.

“I never had the right kind of information growing up, I was just driven by adventure. But I want to make sure that other people do. Because awareness is the first step to change,” she adds. And once you’re aware of sea turtles, it’s impossible not to love them!