Many fishing techniques and practices are destructive to the marine environment. They may cause overfishing, bycatch, damage to the seafloor and sensitive habitats, or entanglements in/ingestion of ghost gear.

Ghost gear is a relatively understudied issue, yet it is thought to be one of the most destructive forms of marine debris. Some of the most problematic fishing techniques that result in a high risk of gear loss (ghost gear) include:

- Gillnets (set and drifting)

- Trawling

- Purse seine fisheries that are associated with drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs)

- Traps and pots

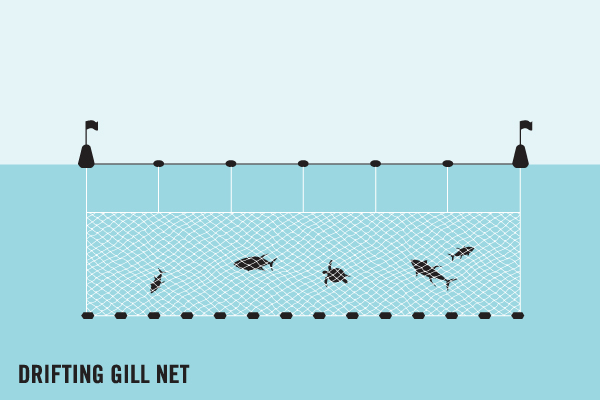

Gillnets

Gillnets are a set of netted panels of uniform mesh size, which form a large netted wall. This wall is intended to catch fish by their gills as they try to swim through the net. The net hangs vertically in the water with a row of floats on the top and a row of weights on the bottom. Gillnets are often made of monofilament material and are becoming increasingly transparent or ‘superfine’ in some regions to increase their catch. As a result, they often break easily.

Gillnet fisheries are of particular concern when it comes to ghost nets, though this does depend on how and where the nets are used.

One of the most significant causes of gillnet gear loss is conflict between fisheries. Bottom trawlers, for example, will often trawl straight through a gillnet and dislodge it or damage the net in some way, resulting in ghost gear. It is estimated that, every year, 24.8% of all gear used is lost in Indian gillnet fisheries, with the main cause being trawler conflict. Even more concerning is the catch rate of this lost gear. Fine-mesh gillnets, for instance, have been shown to have a catch rate of 4 sea turtles for just 100m of net length.

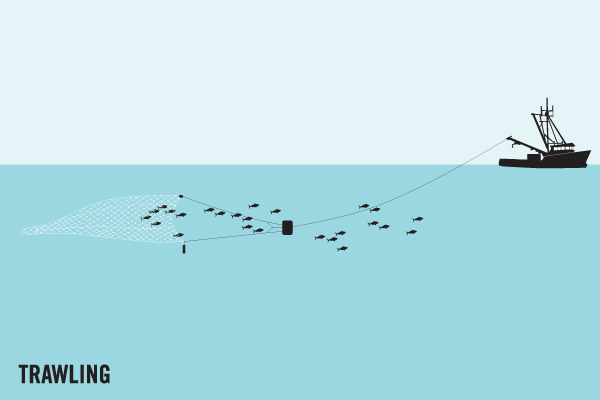

Trawling

Trawling involves dragging a large fishing net with heavy weights behind a boat, either mid-water or across the bottom of the sea floor. The net indiscriminately catches or crushes everything in its path.

The ghost gear that results from trawling tends to be partial loss of nets (net fragments). This is particularly prevalent in bottom-trawl fisheries, where nets often snag on the bottom. In northern Australia, trawl nets were the most abundant net type found stranded on beaches. Similarly, trawl net fragments were one of the major gear types responsible for ghost gear found drifting into the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Maldives.

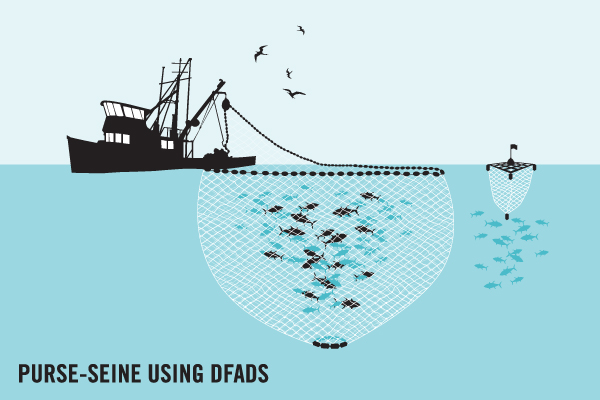

Purse Seine (Fisheries Associated With Drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs)

A purse seine is similar to a gillnet in that it is a long wall of netting set vertically in the water. However, the net is then deployed to surround a school of fish and is pulled tight, enveloping the school (and any other animals) in a purse-like fashion. Industrial purse seines target pelagic fish of all sizes, including tuna, and are therefore frequently used in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, often in combination with drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs).

Though fragments of purse seine nets also contribute to ghost gear, the principal threat of purse seines is its associated use with dFADs. Purse seine fisheries exploit the phenomena of marine life aggregating under floating objects. They do this by deploying man-made floating structures (dFADs) to mimic that of floating natural objects, such as algae or fallen trees. The dFADs then attract marine life and a large purse seine net can be cast around the gathered school of fish. dFADs are usually a square of bamboo with netting and buoys attached. The devices are deployed in the open ocean as drifting devices (dFADs). Sometimes a solar-powered GPS tracker is also used to allow the boat that deployed it to track it.

Despite some dFADs having GPS trackers, fishers will often intentionally leave them if they drift outside of their preferred fishing grounds. In turn, the dFADs then become ghost gear. It has been estimated that 66% of all dFADs deployed in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean are lost, contributing to around 4,000MT of entangling pollution.

Traps & Pots

Traps and pots are usually used to target crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters. They are often baited 3 dimensional devices that allow animals to enter but make it extremely difficult for them to escape. The traps and pots are usually attached to a rope that connects them to a buoy at the surface of the water.

Traps and pots are usually overlooked in terms of ghost gear, but they are prone to ghost fishing since they are often made of longer-lasting, more rigid materials in comparison to other fishing gear. In the Florida Keys, it is estimated that 18% of lobster traps are lost annually in commercial fisheries. This is equivalent to 90,000–100,000 traps when 500,000–530,000 traps are used.

When lost, abandoned or discarded, the traps and pots themselves can continue to fish. This catch can then attract other marine life, including megafauna. In the Florida Keys, for example, dolphins and sea turtles were observed breaking into traps and pots to get to the prey inside, although there were no reports of entrapment here. Perhaps more threatening is that the associated lines that connect traps and pots to the surface can entangle marine life, such as sea turtles.

References

- Adey, J.M., Smith, I.P., Atkinson, R.J.A., Tuck, I.D. and Taylor, A.C., 2008. ‘Ghost fishing’of target and non-target species by Norway lobster Nephrops norvegicus creels. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 366, pp.119-127.

- Arthur, C., Sutton-Grier, A.E., Murphy, P. and Bamford, H., 2014. Out of sight but not out of mind: harmful effects of derelict traps in selected US coastal waters. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 86 (1-2), pp.19-28.

- Banks, R. and Zaharia, M., 2020. Characterization of the costs and benefits related to lost and/or abandoned Fish Aggregating Devices in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean. Report produced by Poseidon Aquatic Resources Management Ltd for The Pew Charitable Trusts.

- Butler, C.B. and Matthews, T.R., 2015. Effects of ghost fishing lobster traps in the Florida Keys. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72(suppl_1), pp.i185-i198.

- Johnson, A., Salvador, G., Kenney, J., Robbins, J., Kraus, S., Landry, S. and Clapham, P., 2005. Fishing gear involved in entanglements of right and humpback whales. Marine Mammal Science, 21 (4), pp.635-645.

- Matsuoka, T., Nakashima, T. and Nagasawa, N., 2005. A review of ghost fishing: scientific approaches to evaluation and solutions. Fisheries Science, 71 (4), pp.691-702.

- Matthews, T.R., Uhrin, A.V., Morison, S. and Murphy, P., 2009, June. Lobster trap loss, ghost fishing, and impact on natural resources in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. In Proceedings of the NOAA Submerged Derelict Trap Methodology Detection Workshop (pp. 34-35).

- Stelfox, M., Bulling, M. and Sweet, M., 2019. Untangling the origin of ghost gear within the Maldivian archipelago and its impact on olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) populations. Endangered Species Research, 40, pp.309-320.

- Suuronen, P., Chopin, F., Glass, C., Løkkeborg, S., Matsushita, Y., Queirolo, D. and Rihan, D., 2012. Low impact and fuel efficient fishing—Looking beyond the horizon. Fisheries research, 119, pp.135-146.

- Thomas, S.N., Sandhya, K.M. and Edwin, L., 2020. Technical guidelines for sustainable small-scale gillnet fishing in India.

- Wilcox, C., Heathcote, G., Goldberg, J., Gunn, R., Peel, D. and Hardesty, B.D., 2015. Understanding the sources and effects of abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing gear on marine turtles in northern Australia. Conservation biology, 29 (1), pp.198-206.