Episode 3

‘Eggsploring’ hatching failure with Alessia Lavigne

Looking at an egg and wondering when and if it ever hosted life is a curiosity most of us are familiar with. But what about sea turtle eggs?

With each sea turtle nest containing anywhere between 60-120 eggs, not all of them hatch into baby sea turtles – some instead exhibit hatching failure. But why do these eggs remain unhatched, and should we even care?

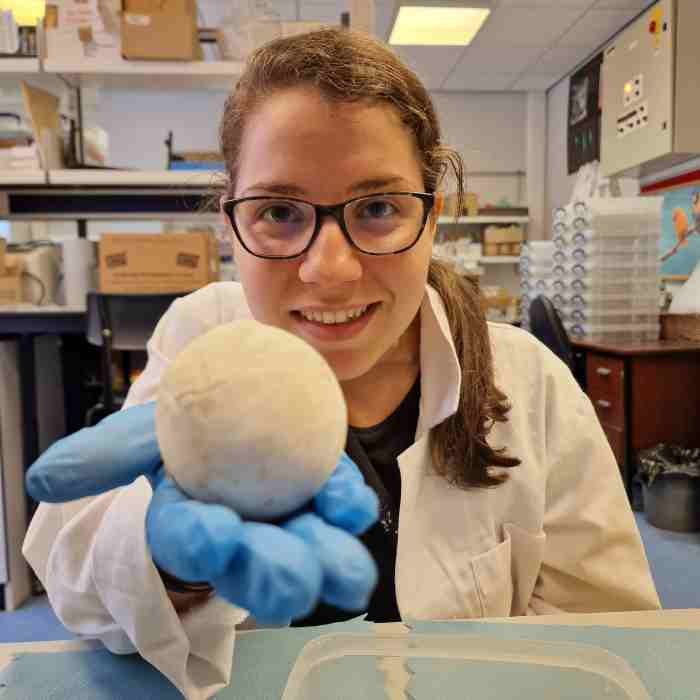

In our third episode, we welcome Alessia Lavigne, a passionate young researcher who believes that hatching failure in threatened sea turtle populations is a cause for concern that demands investigation. After all, eggs hatching successfully is key to ensuring population renewal.

So join Dr Minnie and Alessia, as they crack into the mystery surrounding sea turtle egg development, exploring the reasons behind hatching failures and their implications for sea turtle conservation.

Produced & researched by Anadya Singh, mixed & edited by Dev Ramkumar

Host:

Dr. Minnie Liddell

Guest:

Alessia Lavigne

Episode transcript

Dr Minnie Liddell: Welcome to another episode of Sea Turtle Stories, a podcast by the Olive Ridley Project where we take a deep dive into all things sea turtles.

I am Dr Minnie, sea turtle veterinarian and the host of this podcast

So our guest today for today’s episode is Alessia Levine. Hi Alessia.

Read the full transcript

Alessia: Hi everyone!

Minnie: We’re really excited to have you. Thank you so much for joining us.

So Alessia, a little bit about her is – she’s a PhD researcher with the University of Sheffield and she was born and raised in the Seychelles and spent most of her early life surrounded by the wonderful landscapes and the rich biodiversity there. And these experiences inspired her to pursue a master’s in biological sciences. And she is now currently pursuing her PhD entitled Identifying the Drivers of Reproductive Failure in Threatened Turtles and Tortoises.

She’s working with the Reproductive Behaviour and Physiology Research Group based at the Uni of Sheffield in the UK, where she partners with zoos, captive breeders and conservation groups around the world to work with unhatched eggs from a variety of sea turtle and tortoise species. And excitingly, we at the Olive Ridley Project are one of Alessia’s collaborators. And so we’re collecting samples of undeveloped eggs from our field sites in the Seychelles that she can later analyse in the lab.

Minnie: So really excited to have you here and we’re so excited to learn about all the development aspects of sea turtle eggs from such an ‘eggspert’. So thank you for joining us.

Alessia: Thank you. Hi, it’s a pleasure to be here.

Minnie: So to kickstart things then Alessia, could we start at the beginning and could you tell us a little bit about what happens to a sea turtle egg once it’s been laid?

Alessia: So once a sea turtle lays her eggs, to put it simply, only two things can happen. Either it hatches, so you had a little embryo that fully developed, turned into a hatchling, leaves the nest, or, something along the way went wrong and the egg doesn’t hatch.

So that’s the only two possibilities. They either hatch or they don’t.

Minnie: And so yeah, basically best and worst case scenario. So roughly how long do the eggs spend inside the nest?

Alessia: So if we’re looking at turtles and tortoises as a whole, it can really vary between different species. But in sea turtles, it’s roughly about two months. So there’ll be two months incubating underneath the ground or the sand. And that is when afterwards the hatchlings will come out if everything went well.

Minnie: If everything went well. And that leads us really into your really awesome research. Could you talk to us a little bit about where your research comes in then in this sort of process?

Alessia: To put it in the simplest of terms, my study looks at eggs that didn’t hatch. Eggs that we don’t know why it went wrong and it’s a big mystery and I’ll explain that a little bit more. So part of what I used to do in the field when I was introduced to this world in my first job was that we would go back to these nests. And we would do something called nest excavations. So at the end of incubation, so the eggs have been laid and they’ve had time to develop and hatch, we would return at a safe time where most things have hatched. And we would look at the eggs that failed, so those that didn’t hatch.

And we’d try to understand what stages of development did they stop. And we’d categorise the different eggs. So you’d have some where it almost hatched. And it’s something called when they’ve just pipped, you just have the little hatchling almost got out, but something happened and it didn’t. Or you’d have some that were stuck a different embryo stages.

And it was here that I realised that there was this one group of eggs that was quite mysterious and we just couldn’t classify, in terms of being fertilised or not. You open them up and it’s kind of like a chicken egg. So you just have this yolk and that’s it. You can’t really tell much more about it. And there are some studies or even conservation groups that would just record them as undeveloped. So neither fertilised or unfertilised or even some people would classify it as unfertilised, because we can’t see something. So I questioned this. So just because we can’t see something doesn’t mean it’s not really there.

And it was this idea that I held on in the back of my brain until I eventually went to university and I wanted to test that. And it has now become my master’s and now into my PhD where I wanted to develop these new methods using microscopy that was originally made to look at bird eggs. What I did is readapted those methods to be able to tell in these undeveloped eggs, in these eggs that we can’t tell if something was developing or not, and identify whether they are fertilised on a microscopic level.

We’ve successfully adapted this to five different species and two of these were sea turtle species. So they were the green sea turtles from wild Seychelles populations as well as the hawksbill sea turtle.

Minnie: It might be a little bit technical but what are you actually doing to identify whether these eggs are fertile or not? What’s the process? What are you seeing?

Alessia: Yeah so we get these undeveloped eggs into the lab and we dissect a very special part of the egg where fertilisation takes place and you cut just the membrane that is like encapsulating or covering the yolk, and you cut an area around this special point and we put fluorescent dyes. And that will stain to the nuclei, so this is where all the DNA of either embryonic cells or sperm cells is contained and it will only attach to, the dye will only attach to the nucleus of these different cells. So then you allow that to develop a little bit and then you put it underneath another special microscope known as a fluorescent microscope that will allow this dye to be very shiny and blue and this is how we can see it through the microscope.

So if we see these very shiny blue dots that’s usually how it looks like if we do find embryonic cells and this is how we know it’s fertilised you see lots of shiny blue dots it’s very pretty actually.

You can tell the difference between the sperm cells because their shape is a little bit different and sometimes you can even see their tail. So you can tell the difference between for instance embryonic cells or even sperm cells or of course there is the possibility that there is fungal infection, these eggs have been underground for two months. It’s, you know, you can find other things as well. However their shape is very distinctive and you can still tell the difference between the different things you’re looking at so normally if you do see your little round blue cells, that is your embryonic cells and you’re like ah yeah okay something did happen, fertilisation did occur and you know this egg was fertilised.

Minnie: So you see that you see the blue dots and we know then at that point that the egg failed because of early embryonic death and something else, rather than not being fertilised. So is it really quite binary you know you see that and it’s definitely fertile versus um can you ever see maybe, like, just sperm or something like that. Like is there ever a chance it’s just sperm and nothing else?

Alessia: No that’s a good question that’s a good question. So one of the challenges we do get is that again these eggs have been underground for quite a while you will have eggs that are quite disintegrated, so very often you will not get perfect samples that arrive in the lab you won’t find exactly the spot that you want even in the best samples of turtle and tortoise eggs, you may not find it for some strange reason. So the challenge that we have is to have enough material to keep searching for those little blue dots until you can definitively say yes I have found them or no I haven’t found them.

If we do find these blue dots it is quite binary, like yes it is definitive you did find embryonic cells. If you didn’t though, this is where it gets a little bit tricky. So to know if it was unfertilized you need to have quite a good sample that you say okay you’ve been very thorough you look at the entire membrane of the yolk you didn’t find any cells then it is very probable it was unfertilized. However, if let’s say you don’t have everything you don’t have an entire intact sample you have to maybe rely on other information.

So for instance this is when you start looking at the number of sperm. So in the number of sperm cells, so if you find very few sperm cells that have made it or none, here you can put like, it’s you know it’s quite likely that it was unfertilized, no sperm or very little sperm cells made it, there you can be like it’s quite unlikely that it was fertilised. Or if you actually find plenty of sperm cells and that does happen like you can see them like in the hundreds then but maybe you don’t find embryonic cells you still have to rely on a probability that probably one or a few of these sperm cells did fertilise the egg but you didn’t have enough material to determine this definitively because you didn’t find the cells. So it really does depend how intact your samples are but you can still infer some type of knowledge.

Where it can be considered inconclusive is let’s say you have a very disintegrated sample let’s say you have less than half of the material that you need then you will have to say okay it’s inconclusive, you’re not sure you didn’t find many sperm cells you didn’t find any embryonic cells so there you would normally consider that as inconclusive. It’s still a major step forward because in the current methods that we would have, we wouldn’t even be able to tell if these eggs were fertilised so it’s still more information that we would never have had in the first place.

Minnie: So that’s really the crux of it isn’t, it that’s like you say it looks like a yolk it’s just a yolk in an egg white and you look at that and you can’t see anything, there’s nothing of any you know there’s no cells there’s nothing on there it’s just a yolk, and so yes of course everyone’s like well maybe this never had an embryo in it in the first place but obviously did that distinguishing factor of did it come out of the female unfertilized and there was no chance of anything ever forming because it was just a yolk and nothingness or did actually it was fully ready to go but something else stopped it from happening. Why is that actually so important for us to understand the difference between the two from a conservation perspective?

Alessia: Oh yeah I love that question, so this difference is very important because the causes behind fertilisation failure and early embryo death are very different. So if we understand these different causes we can come up with the right solutions to address them. So I really like to use the example. I know this is a sea turtle podcast but I really love to use a tragic example of the yangtze giant softshell turtle. So this is arguably the most, I dare say endangered animal, point blank on the planet. We had reached the point where there were only four known individuals in existence, one of them was a female and of course they had tried to put her in captive breeding programs and even resorted to artificial insemination, nothing was working she was in this program for over eight years – all of the eggs she was producing was undeveloped so they all looked as if they just had a yolk nothing was developing and they just had no idea what was happening and they were just trying and trying and trying. And it is in this situation where this method would have been perfect because you would be able to understand are these eggs failing because of early embryo death – so does that mean it’s an incubation you know problem are maybe incubation conditions not the best, is it too hot, is it too cold, is it some developmental issue, or if it was the alternative and maybe we did find out that these eggs are not fertilised so they’re unfertilized, we would have been able to say go back and look at their behaviour – for instance maybe copulation isn’t happening, maybe their conditions in their habitat that they were given was too stressful for them. So it would have informed conservation groups to go back and re-evaluate in the right places instead of just guesswork, which is what was happening. And sadly this method even though it’s been developed now will never be able to benefit the yangtze giant softshell turtle, because in 2019 I believe she died. So right now this entire species is functionally extinct there’s about maybe just three or four males. So this is exactly the kind of thing we want to avoid using this method.

So as a whole, turtles and tortoises are known as the order of Testudines. It is one of the most endangered vertebrate groups on the planet, over 50 percent of all turtle and tortoise species are at risk of extinction. 20 percent of them are considered critically endangered. So this type of method, as we’re moving forward with climate change and all of the effects that we’re having on wild populations as humans we really need this method to start removing the guesswork and drive conservation in the right direction because this requires money and time that is not friendly in the world of conservation. So we need to cut this guessing game and start getting to the point quickly because otherwise you’re going to have more stories like the yangtze giant softshell turtle and we don’t want that.

Minnie: Definitely because I think things like infertility issues, if we look overall at the female we think okay well if these eggs are not developing there’s something wrong with her. But actually if there are fertility issues it could very well be a male based population issue as well.

Alessia: Yeah

Minnie: Well in sea turtles it’s historically very hard to look at males because they are just much harder to get hold of, they don’t come ashore so we don’t really get a chance to research them as much, but yeah it would definitely obviously mean that the finger, not finger pointing that’s the wrong word – the boys are the problem – but the issue would be that it’s not their fault it’s not the female’s fault or the male fault, but we actually don’t know where to where to look.

Minnie: Yeah and the extra thing that i really love about this method especially if we do look at sea turtles and the challenges we face when it comes to looking at any aspect of the male is that not only can we see the cells of um like embryonic cells, we can also see sperm cells so we can actually get even more information on the reproductive health of males. So you can actually count how many sperm cells arrive to the egg but also you can see the morphology so the shape or how the sperm cells look like – so if for example you find a very few sperm cells that make it, or they’re very strange shape there they don’t look very normal, from there you can think oh maybe there is a reproductive health issue with the male. So you don’t only learn about the success of the egg but you can also infer further knowledge about the males in the population and I think that’s very interesting when it comes to this method.

Minnie: Yeah that is really interesting, we would actually probably never really get hold of male sea turtle sperm if it was not for looking at these sorts of ways. We know in other species that there are some key drivers of like male fertility, they have to do with pollution or dietary components and I imagine that would change depending on certain populations as well.

AD

The Olive Ridley Project is a charity committed to protecting sea turtles and their habitats. You can support us in our mission by donating or adopting a sea turtle on our website oliveridleyproject.org. Your contribution will help us rescue and rehabilitate more injured sea turtles, conduct scientific research and grow our education and outreach programmes. Together, we can ensure that sea turtles have a fighting chance.

Minnie: So I guess maybe coming on from that, how often are we having difficulties with eggs developing? Do we have kind of numbers on that? Do we know how much of a contribution that is making to the species endangerment at large?

Alessia: So I would say, again, it really depends on what group of turtles and tortoises we’re looking at, which species and where on the planet. And also the effects human effects that we have on them. So even just looking at sea turtles is a huge variety of how much hatching failure can be affecting a species. So, for example, the leatherback sea turtles, they have a bit of a history of entire clutches failing. So you can have up to 100% of clutches failing. And we don’t really understand why. And they all look undeveloped.

And anecdotally, I’ve also spoken to Dr. Jeanne Mortimer. And she’s also kind of mentioned that as well, where you can have entire clutches of sea turtle nests failing.

And that would be, you know, maybe a bit more common in some species than others. But even within one species, when I think of studies, for example, in green sea turtles, you have the green sea turtles in Seychelles that have a relatively high hatching success. And there won’t be that much of hatching failure.

But if you look at green sea turtles in Oman, for example, there is an actual concern of such a high rate of hatching failure. And a lot of, again, undeveloped eggs. And you have these papers talking about, well, again, not really knowing at what stage this is happening.

So is it due to a fertility health problem in the adults? So maybe there’s a concern of heavy metals to be like specific in pollution. So is the pollution affecting the fertility, the health, the reproductive health of the adults? Or is it because it’s seeping into the egg and causing like early embryo death? So again, this is where understanding this difference is so important in conservation, because you’re going to start understanding where should we start focusing our research to know how to help. And yeah, so it’s quite variable.

We’re going to require custom solutions, there won’t be a generic fix, fix all bandaid. So we really need to start understanding in each species in each location, what is going wrong and what we can do.

Minnie: So the turtles that you’re looking at you’re doing greens and hawksbills, which are two of the species found in the seychelles. Have you thus far noticed a difference between those two in the eggs that you’ve analysed from those two different species?

Alessia: So here in the Seychelles I have to admit that we have a bias towards the critically endangered hawksbills. Because here in the Seychelles we just have a lot higher number of them, compared to the green turtles where I’ve had much less in comparison. Despite that, the eggs that I was able to look at that were undeveloped and I could successfully evaluate – both of them showed that undeveloped eggs – their main drivers of failure is early embryo death, so no there hasn’t been a remarkable difference between these two species that i could find.

The only sample that I did consider unfertilized was from a very strange hawksbill nest where multiple things were wrong. So that for instance was from a nest that immediately something was off. Um you had eggs that were either unnaturally very small or unnaturally very large. Um then the only few eggs that did hatch there was dwarfism, so the little hatchlings were like dwarfed and when you opened the eggs to look at them they had multiple yolks. So the sample that I took um into the lab to look at, had three yolks well in one egg. Fortunately, I managed to preserve all three yolks very well and I could look at every corner of that membrane and that was the only sample where it was considered unfertilised.

In the Seychelles, it does look like undeveloped eggs are failing more because of early embryo death and there hasn’t been a difference that I could find at least at this point between the two different species that I’ve been working with when it comes to sea turtles.

Minnie: That’s interesting, I guess that could just be a single turtle problem. I guess there was a potential that she as an individual or perhaps the male she mated with individually in an isolated moment had uh some kind of abnormality. I read some research that was talking about how sometimes if the females can’t nest in a certain time frame, uh the eggs will stay in their body in their oviducts for an extended period of time and this can also lead to early embryonic death – in that they were fertile but they didn’t actually get out of their body in time um and so therefore there were problems. And sometimes females with their shell glands, so their actual kind of reproductive tracts can end up producing very strange shells or dropping more yolks than they should and I guess these may be i guess there could be lots of factors genetics nutrition all sorts of things that they could have come across, um hopefully more research ongoing but yeah that sounds like a strange strange nest.

Alessia: And you know in Seychelles we’ve been monitoring sea turtles for about 50 years. So actually we know specifically the female who had you know produced this egg and now the conservation team knows okay maybe there is something odd with this female, we can keep an eye on her. So this is again informing conservation teams on what we need to be looking out for, that thanks to these methods we were able to tell the conservation team that something was odd there, maybe keep an eye on this female and the consequent nests that she will make in the future. So no matter what the results are it’ll always be useful and I think that’s such a great thing about this method.

Minnie: Yeah that’s really really interesting, the discussions about or the stories of individual turtles always really appeal to me. So from the research you’ve thus far done on the Seychelles sea turtles, their fertility is actually seemingly fine. These eggs are fertile there’s no reason technically speaking or biologically speaking why they shouldn’t be able to develop into a baby turtle, but there are other external possibly environmental factors then that are driving them not being able to develop past the point of – of the little I guess is it blastocyst at this point that just the little the little combination of sperm and egg it’s not getting past that stage. I suppose that probably leads me into my next question actually, which is, what are some of the causes that we know of for early embryonic death? What is causing these fertile eggs to not actually be able to develop past that point?

Alessia: So there’s a lot of possibilities we don’t know specifically now what is causing early embryo death, so it could be things like pollution, it could be things like increased global temperatures, so right now we’re very concerned about rising temperatures killing off eggs. So this method for instance in that situation will be extremely important to know at what point in development is heat killing off eggs. So now we have this method to actually go down to the cellular level. So now we can determine are eggs dying at a cellular level or is it later on. These little differences are so important in conservation because it tells us when we should intervene and that is something so crucial moving forward in a world of climate change and global warming. We can also look at the effects of different types of pollutions, contaminants, there’s also genetics that could be another possibility, where i’m thinking for instance you have very small populations maybe they’re all very related to each other and maybe you’re concerned that there is like too much similarities in genetics and sometimes that can cause issues in development – so it could be various different things. These three examples I gave in terms of temperature, genetics and pollutants and contaminants are just three but it can still point us in the right direction given a little bit more context.

Minnie: And yes, but we know for example in the time frame that eggs can shift so for the first 12 hours after laying, eggs can actually move and that can be okay, but after that point the embryo then attaches and it can actually then be really disrupted by movement at that stage. In a practical sense that can happen if eggs are disturbed after they’ve been laid by humans or by predators and that will cause early embryonic death. So Alessia, can I ask you a question regarding hatcheries – so hatcheries being a conservation technique where we will take the eggs from the beach and we will move them to sort of a controlled area, sort of a safe location in order to prevent some of the things you’ve mentioned. Do we think hatcheries and being in a more controlled environment can prevent early embryonic death?

Alessia: So when it comes to hatcheries, I think it’s very situation dependent. So not all hatcheries are going to be the same all around the world. So I feel that there is great potential if we find the correct hatcheries with the correct ways to be able to monitor them and the correct conditions, but right now it’s a bit of a challenge to be able to determine what is a great hatchery.

And also thinking of it in a different perspective is for instance here in the Seychelles we have noticed increasing erosion of our coastlines. And you know we, obviously as conservation teams you do not want to interfere with nests unnecessarily, but now that there is this increased coastal erosion there are many partners that feel that they are forced to have to intervene and we do nest translocations, so that is when conservation groups will have to take entire nests and carefully move them to somewhere that’s safer and you would only normally do this as a last resort if the entire nest is at risk of failing. So when we have a situation like this where we have entire coastlines disappearing, these eggs would have just been all washed into the sea, you do have to do something about it otherwise you’re going to lose everything.

Minnie: Yeah that’s actually a really good point, because there are some pitfalls to hatcheries, we’ve got an interesting episode coming up where we’ll talk about hatcheries and about some of the issues they can face but also some of their successes.

I suppose actually I was going to ask you a slightly different question in sort of a general conservation term, as a young scientist yourself, do you have any sort of advice for other young people who are pursuing research into conservation or want to kind of be in that field?

Alessia: I do feel that as a person you need to be very resilient, you need to be very, almost borderline stubborn. Like, you need to be able to question what’s there, if you are going to go into this field I think a lot of people, not just myself but others, we all share that in common that we have. We’re curious and we’re also very determined to meet our needs to like, know why this is the way something is, so I feel that you need to have that very strong-willed curiosity. If you’re pursuing science there will be very challenging subjects and you need to be driven by passion more than just trying to get good grades, you need to be interested in what you’re doing, and that is what is going to push you so when you don’t have motivation. You will not always be motivated, you need to be disciplined through your passion and interest. and if you want to inform yourself on whether this world is for you or not please follow me at turtle explorer on instagram or tiktok.

Minnie: it’s a great Instagram, I highly recommend it as well.

Alessia: Because I share insights from my career as a PhD student, as a researcher exactly in this field. So if you do have an interest to know whether it is for you, what is the daily life like, what are the things you see and work with in the lab, on the field, this is exactly the stuff I share. I’m very engaging with people who ask questions and comments so yes, go there.

Minnie: Agreed! And I can highly recommend your instagram, I enjoy it hugely, I know I think it’s great and yeah you’re really doing an amazing job of spreading out that information to interested parties and it’s just such a really interesting field of research, so thank you so much for sharing all of that insight with us. I think our listeners probably will have a pretty good idea now of what’s going on in that nest and why it’s relevant to everything that we want to do with sea turtles. So thank you so much for joining us today.

Alessia: Thank you for having me. It has been a pleasure.

Minnie: Thank you all, to everyone who is listening. We would love to hear your thoughts, so please do leave us a review and let us know.

If you would like to learn more about sea turtles and ORP’s work, please visit our website oliveridleyproject.org, where you can also support our work by naming and adopting a sea turtle, adopting one of our sea turtle patients or making a donation.

You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn and YouTube to stay up-to date with the world of sea turtles

We’ll see you for our next episode, and until then, stay turtley awesome.

Further reading, sources & references

- Understanding early reproductive failure in turtles and tortoise by Lavigne, A. M., Bullock, R., Shah, N. J., Tagg, C., Zora, A., & Hemmings, N. (2023). bioRxiv.

- A field key to the developmental stages of marine turtles (Cheloniidae) with notes on the development of Dermochelys by Miller, J.D., J.A. Mortimer & C.J. Limpus.(2023). Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 16: 111-122.

- Failure to launch: what’s happening with Seychelles’ turtle and tortoise eggs? A project by Alessia Lavigne

- Alessia’s Instagram

We would love to hear your questions, comments or suggestions about the podcast. Email us at: seaturtlestories@oliveridleyproject.org